Smartphone Photo Color Problems? Spectricity Expects to Fix Them

At CES, a startup shows a multispectral camera that fits into a smartphone.

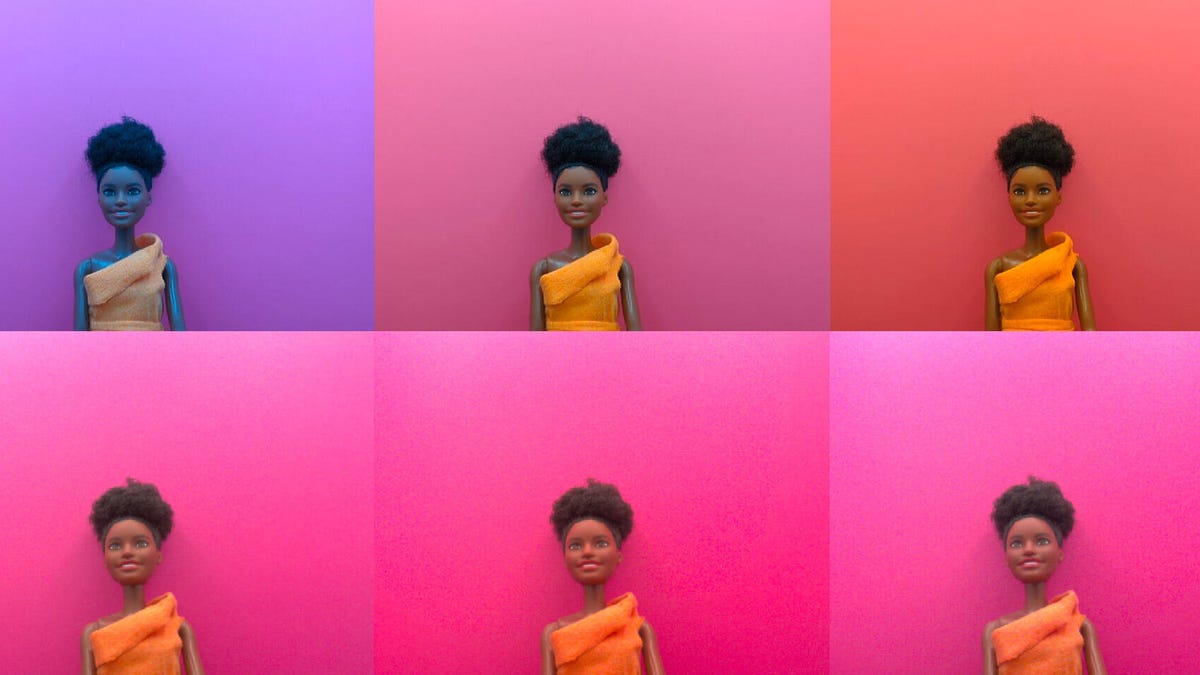

Spectricity's multispectral camera can correct color problems in smartphone photography. The top three example photos, taken with a Google Pixel 7 Pro, show significant color changes in a scene when taken with warm, neutral and cool lighting. The bottom three photos, boosted with Spectricity's 16-color camera image, show truer and more consistent color.

A startup called Spectricity hopes its special purpose camera that captures 16 different colors will mean your future phone will be able to handle the subtleties of real-world color more capably.

The company has developed a very compact form of what's called a multispectral camera, a module that captures many more frequencies of light than the red, green and blue of traditional digital cameras. By marrying its multispectral image data with the photo taken by a traditional camera, the system can better navigate tricky lighting situations, improve skin tones in photos, boost apps for makeup choices and dermatology diagnoses, and help with online purchases where accurate color matters.

"Smartphones are colorblind. It's a problem all smartphone makers are trying to solve," said Chief Executive Vincent Mouret, who leads the 35-person spinoff from Imec, a prominent chip research and development center in Belgium. He spoke from the CES 2024 show, where Spectricity is showing off its S1 multispectral camera, now squeezed down to fit in a phone.

Indeed, the company has at least three customers that he expects will include Spectricity's camera in 2025 phones.

Cameras are arguably the highest profile aspect of any new phone and the main reason many of us upgrade. They're getting steadily better as phone makers increase sensor size, add new cameras for ultrawide and telephoto perspectives and improve computational photography software that milks better shots out of small image sensors. Phone makers are desperate for an edge that helps them stand out over rivals.

It's not clear just how often Spectricity's technology would improve a photo. Not every shot is complicated by unusual lighting or difficult situations, like mixed lighting with both warmer-toned indoor lights and cooler outdoor sunshine.

But color problems can be significant, as evidenced by the effort companies like Google and Apple are investing into truer rendering of skin tones, especially for people of color.

Michael Jacobs, a Spectricity application engineer, demonstrated the company's technology by taking a photo of a doll portraying a Black person against a pinkish background. Google's Pixel 7 Pro shifted the color dramatically, giving the doll's face a blue cast and turning the wall purple. The same shots modified by the Spectricity color information showed much more natural tones.

"We can detect the face in this multispectral image and then find the illuminance that is shining on that face," Jacobs said. "We use that information to correct illuminance and then end up with the correct color for that face."

Spectricity isn't alone in its interest. Marc Levoy, a researcher at Adobe and formerly at Google, who pioneered computational photography, sees multispectral sensors as an avenue for smartphone photography improvements.

Fitting a multispectral camera into a smartphone

Spectricity's S1 camera module, including the image sensor and the company's own lens, fits into the small volume of a regular smartphone camera module. It'll cost only about $3. A more significant concern for smartphone makers could be the volume the camera occupies, since every cubic millimeter inside a phone is precious.

The image sensor filters light by using interference patterns that thin transparent films can cause, either transmitting or reflecting particular frequencies of light depending on the thickness of the film. It's what causes the rainbow patterns you can see when oil is spilled on a puddle in the road.

Spectricity's sensor has a 5-megapixel resolution, but since each pixel captures only one color, it yields a 640x480 image with all 16 colors per pixel. Processing those color combinations for each pixel is what allows Spectricity's technology to infer the true colors of a scene, the company says.

The S1 produces a relatively low-resolution image compared to smartphones that typically take 12, 24 or 48 megapixel photos. But the color data can be mapped to the full-resolution shot. The S1 works in conjunction with a phone's camera and doesn't replace it.