Apple's M1 Ultra Shows the Future of Computer Chips

Packaging chip elements together cleverly extends progress even as chipmakers struggle to maintain the pace of Moore's Law.

If you want a glimpse of where the processor business is headed, check out Apple's new M1 Ultra processor.

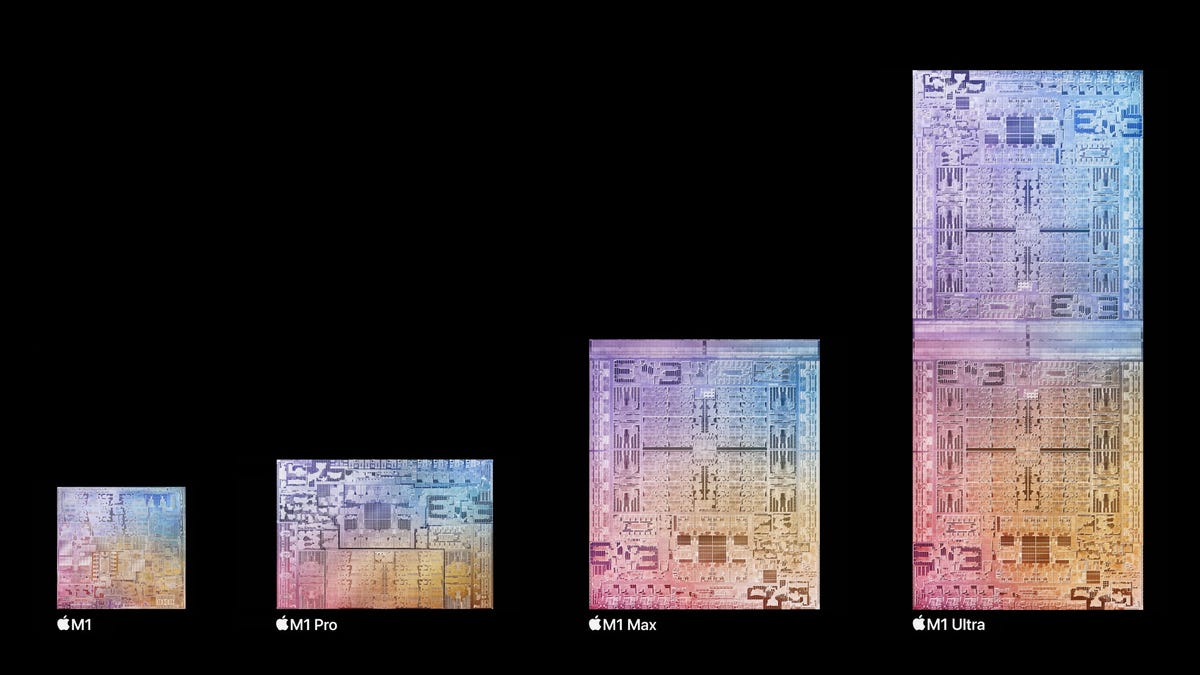

To deliver speed and performance, the consumer electronics giant married two of its older M1 Max chips using advancements in a once humble aspect of chipmaking called packaging. Packaging no longer just provides a protective housing but now also offers cutting-edge communication links.

By combining the two chips, Apple's M1 Ultra delivers a stunning 114 billion transistors that make up 20 processing cores and 64 graphics cores. By comparison, AMD Ryzen desktop processors use something like a tenth that number of transistors.

The M1 Ultra highlights the progress chipmakers have achieved in keeping Moore's Law alive. A dictum in the chip industry, Moore's Law predicts that the number of transistors on chips doubles every two years. Transistors, the basic circuit elements that process data, have been harder to miniaturize, which has slowed the progress initially charted by chip pioneer and Intel co-founder Gordon Moore. Advanced packaging offers a new way to bump up those transistor counts.

Apple isn't the only company working on advanced packaging technology to link chips together. Intel, AMD and Nvidia also have technology to combine multiple chip elements, called dies or chiplets, into a single larger processor. The M1 Ultra is arguably the most advanced example of the concept so far, but it won't be the last.

"You'll see it in mainstream PCs over time," said Tech Insights analyst Linley Gwennap, not just the Mac Studio systems costing $4,000 and up.

See also

Chip packaging advances

Packaging has been around for as long as chips have been. Initially, it involved a housing to protect a processor and provide it with the electrical links to memory, communications and other elements of a computer. Over the years, it's gotten more and more complex. Now chipmakers see advanced packaging as a crucial element in sustaining computing progress.

Fine lines in these Intel Meteor Lake test chips show how multiple chiplets make up the whole processor.

Apple's UltraFusion, the name of its packaging technology, uses a narrow silicon slice called an interposer that resides beneath the two M1 Max chips, linking them with 10,000 wires that can carry 2.5 terabytes of data per second over a very short distance. That enormous speed is necessary so chip cores on one die can reach memory that's connected to the other. Graphics processing units in particular have an insatiable appetite for data stored in memory.

Interposers historically have been large and expensive. Apple's custom approach involves a narrower slice that only traverses the connecting edges of the M1 Max chips.

Intel has developed a similar packaging technology, which it calls Embedded Multi-Die Interconnect Bridge. Intel hasn't used EMIB in any chips that are on the market yet but expects to begin selling one, a high-end server chip codenamed Sapphire Rapids, later this year. Sapphire Rapids will use EMIB to link four chips and four big memory modules, too.

UltraFusion's more expensive, densely packed wires lets Apple send data from one die to another roughly twice as fast as Intel does with Sapphire Rapids, said Real World Technologies analyst David Kanter.

Advanced packaging doesn't solve every problem. At twice the size of an M1 Max, the M1 Ultra consumes about twice the power and throws off twice the waste heat, a big design constraint for computers. Don't expect to see it in laptops.

Mix and match chiplet assembly is unusual today, but it'll become more ordinary. An alliance of almost all the world's top chipmakers should make it easier by developing standardized interfaces chiplets use to talk to each other.

Advanced chip packaging on the way

Apple's M1 Ultra is only one instance of new packaging methods. Larger interposers have been used for years, in particular by a very flexible but very expensive type of chip called an FPGA. More recently, it's taken steps toward the mainstream.

Intel's Sapphire Rapids chip, the next-gen Xeon model for the thousands of servers that pack data centers from companies like Google and Facebook, will include a model with four chips married into one. Its chiplets are connected with EMIB, which like interposers is a packaging approach called 2.5D since it's a step beyond the purely two-dimensional packaging used before.

Last year, AMD Chief Executive Lisa Su showed off a packaging technology that stacks chiplets one atop another, called 3D packaging. The first chips using the technology will be Ryzen 7 5800X3D gaming PC chips expected in coming weeks. AMD uses its approach, called 3D V-Cache, to bond high-speed memory chips into a processor complex for a 15% performance boost compared with conventional data links.

Intel, too, plans to use its 3D stacking technology, called Foveros, with 2023 PC chips code named Meteor Lake.

Both EMIB and Foveros also figure into this year's Ponte Vecchio processor, Intel's gargantuan graphics and AI chip geared for the Energy Department's Aurora supercomputer. "Ponte Vecchio is the apotheosis of advanced packaging," Kanter said.

Advanced packaging's high costs

Ponte Vecchio also embodies one of the problems of advanced packaging: expense. Designing, sourcing, aligning and bonding chiplets all adds complexity and expense to chip manufacturing. That means extra cost.

AMD CEO Lisa Su holds a prototype Ryzen chip with 3D V-Cache memory chiplets bonded on top for faster performance.

Apple's Mac Studio computer is a case in point. It has a starting cost of $1,999 with the M1 Max processor but costs $3,999 with the M1 Ultra. If you want the most powerful version of the chip, with 64 GPUs, add another $1,000 to the price tag.

"Yes, it's possible to keep Moore's Law going, to continue to pack more and more transistors into a package, but we're not doing anything to address the cost," Tech Insights' Gwennap said. "A lot of practical issues need to be worked out before we get to this utopia where you buy a lot of chiplets, plug them together, and everything just works."

For more, take a look at everything else Apple announced Tuesday, including the iPhone SE 3 (here's how it compares to the 2020 model and why it's for people "who just want an iPhone"), new iPhone 13 colors, and the upgraded iPad Air, as well as the Mac Studio and Mac Studio Display. The products arrived alongside iOS 15.4, Apple's latest iPhone operating system update. You can explore all those products and more with CNET's event recap.