Apple's M1 Ultra Chip Shows Healthy Future for High-Powered Macs

The chip highlights the dramatic shift in how Apple powers its Mac lineup.

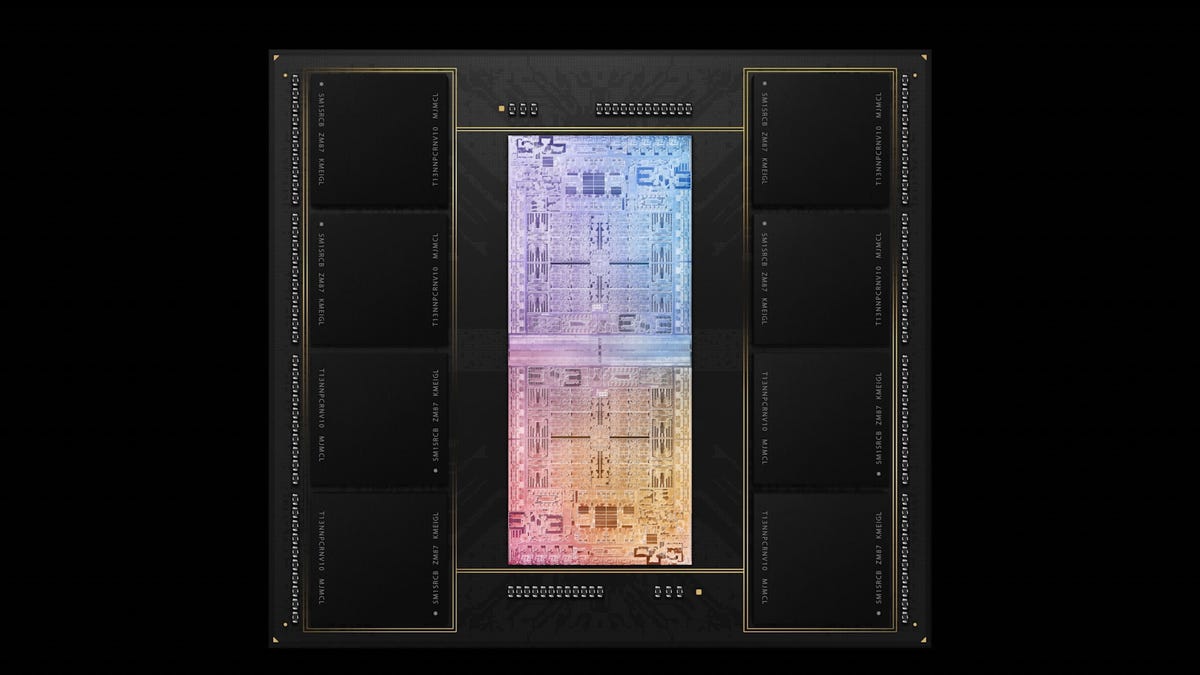

Apple's M1 Ultra combines two M1 Max chips into a single processor.

When Steve Jobs unveiled the first iPad 12 years ago, the Apple co-founder touted the homegrown chip inside the tablet computer, promising, "It screams." Since then, Apple has improved the designs of its homegrown chips, which now power its iPhones, Apple Watches and other products.

On Tuesday, Apple took the wraps off its latest chip, the mammoth M1 Ultra, which will serve as the brains of its new Mac Studio computer. Essentially two chips in one, the M1 Ultra uses a high-speed link called UltraFusion with 10,000 tiny wires to join two M1 Max chips and their memory banks. It extends Apple's winning approach to efficient performance and is made of an eye-popping 114 billion transistors, the fundamental element of chip circuitry.

"It's super clever," said Creative Strategies analyst Ben Bajarin. "It basically doubles overall performance."

The M1 Ultra should calm the nerves of anyone worried about the health of Apple's Mac products as the company shifts away from Intel processors to its own M series chips. A high-end processor, the M1 Ultra is designed for customers who can afford to spend big on computers for editing 8K movies, rendering 3D animations and building software as fast as possible.

For most of us, the nuances of chips are less important than their utility. We just want our gadgets to work.

Still, Apple's growing chip prowess has already made waves around the tech world, pushing industry mainstays and Intel, a former supplier, to concentrate on better battery life without sacrificing performance. Other tech giants including Microsoft and Google are pulling a page from Apple's playbook by developing their own chips in house. Even Facebook is designing its own chips for accelerating AI.

See also

"Apple silicon has had a profound impact on the Mac," CEO Tim Cook said during Tuesday's event. "Every quarter since we started shipping in M1-based Macs has been record breaking, and we've outpaced the industry growth."

The M1 Ultra is an extension of the M1 processor line, which debuted in November 2020 in the MacBook Air. The laptop's slim chassis benefited from the power-efficient chip design, which is a variation of the processors in Apple's iPhones and iPads.

Later versions -- the M1 Pro and M1 Max last year -- brought Apple-designed chips that could power the company's bigger MacBook Pro laptops. Though Apple designs its processors, it relies on Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. (TSMC) to build them.

Intel, now almost completely ejected from Mac products, expects its own chip technology will outperform rivals' devices by 2025. "We're focused on developing and manufacturing world-class CPUs that will outperform anything else other companies put out into the market," spokesperson Thomas Hannaford said.

Apple charges a princely sum for the M1 Ultra. The base price of a lower-end Mac Studio sporting an M1 Max is $1,999. Upgrading to an M1 Ultra doubles the bill to $3,999, though it also doubles base SSD storage capacity to 1TB and memory to 64GB. A tricked-out Mac Studio with maximum storage and memory will set you back $7,999.

Apple's M1 Mac processor family began with the M1 in 2020 and has expanded -- literally -- with the M1 Pro, M1 Max and M1 Ultra.

The M1 Ultra links the two M1 Max chips with silicon technology called an interposer that sits underneath the chips. The technology exemplifies new trends in chipmaking that let processor makers mix and match multiple "chiplets" into a single more powerful processor. That can boost performance, but the extra materials and manufacturing steps also add cost.

"This is the most sensible way to do it," said Real World Technologies analyst David Kanter. "It's just ludicrously expensive."

The Mac Studio's intended market, professionals who benefit from every moment saved in editing video or building software, spend lavishly for top performance.

The speed and power of the M1 Ultra might make the Mac Studio appealing to a new group of potential buyers: gamers.

Historically, gamers have preferred Windows PCs, which are easier to configure and overclock for maximum speed, to Macs. For those gaming rigs, Nvidia and AMD supply external graphics processing unit chips for maximally lavish gaming visuals.

Apple's M1 chips, though, have the same unified memory architecture that game consoles employ, a single memory bank shared by a processor's CPU and GPU cores. The unification helps developers since they don't have to worry about copying data back and forth from different memory banks. With big graphics horsepower and up to 128GB of unified memory, both game developers and gamers might become interested in Macs.

The M1 Ultra's costs and Mac Studio pricing fit with Apple's premium product philosophy. The relatively high price means a broad, cost-sensitive part of the market sticks with PCs that run Microsoft's Windows or Google's Chrome OS. College students and families buying new PCs for kids' online schooling don't always have $1,000 or more to spare.

"It's hard to find people who aren't interested or don't want a Mac," Bajarin said. "They just can't afford them."