After 2 Years of COVID, Scientists Still Don't Have Answers to These Vital Questions

Two years after President Trump declared a state of emergency, experts struggle with long COVID, vaccine effectiveness and more.

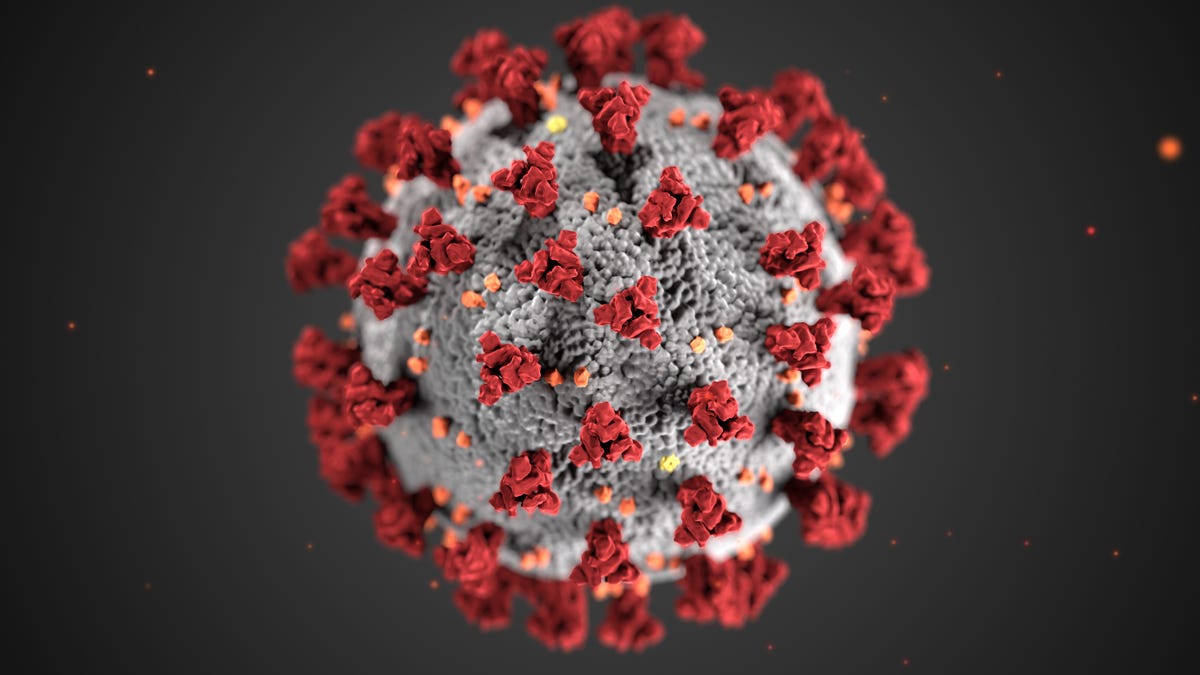

A COVID-19 molecule.

On March 13, 2020, US President Donald Trump issued a state of emergency in response to COVID-19, two days after the World Health Organization announced the outbreak could be characterized as a pandemic.

At that time, fewer than 2,000 Americans had tested positive for the virus. Today, there have been 79 million cases reported in this country, and more than 965,000 deaths.

Advances against SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, have come relatively rapidly: By the end of 2021, multiple effective vaccines had been approved and Pfizer had received FDA authorization for its COVID antiviral drug Paxlovid, which the pharmaceutical company says could cut the risk of hospitalization or death by up to 89%.

Two years on, with a global death toll of more than 6 million people -- and tens of millions more infections and hospitalizations -- scientists are still struggling to understand major aspects of the disease.

1. How many COVID-19 booster shots will we need?

With vaccines' protection waning over time and the continuing evolution of variants, health experts expect more booster shots will become the norm.

In a Feb. 16 press briefing, White House Chief Medical Adviser Dr. Anthony Fauci said, "The potential future requirement for an additional boost -- or a fourth shot for mRNA or third shot for Johnson & Johnson -- is being very carefully monitored in real-time."

A fourth vaccine shot could be coming as early as fall 2022.

The CDC has updated its guidance to indicate that some immunocompromised people can get a fourth COVID-19 shot now, while Israel, Germany and other nations are researching the efficacy of a fourth shot for the general population.

Moderna President Stephen Hoge said we will most likely need seasonal COVID-19 boosters, much like we do with the flu, at least to protect those at the highest risk of infection and serious illness.

2. How long does immunity from vaccines last?

The first COVID-19 vaccines went into people's arms in the US in December 2020. The two most effective -- from Moderna and Pfizer/BioNTech -- took a unique approach: using Messenger RNA (mRNA) to teach our cells how to make a protein that triggers an immune response to the virus.

While researchers have been studying mRNA vaccines "for decades," according to the CDC, this marked the first time they've been made available to the public. Scientists continue to gather information on how effective they are, and how long until their effectiveness begins to decline.

"We are definitely still figuring that out," Gronvall said. "We're seeing that protection wanes earlier than six months, which is why boosters are being recommended at six months."

In a recent weekly report, the CDC announced that protection against hospitalization from mRNA vaccines dropped noticeably after just four months, even with a booster. When delta was predominant, protection against hospitalization was 96% within two months of a third mRNA shot, but dropped to 76% within four months.

During the omicron variant wave, protection from hospitalization fell from 91% within two months of an mRNA booster to 78% after four months.

According to the World Health Organization, the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines are far less effective in preventing infection by the omicron strain than earlier COVID-19 variants. Other vaccines -- including those from Johnson & Johnson, AstraZeneca and ones manufactured in Russia and China -- do even less, The New York Times reported.

Still, fully vaccinated individuals are much less likely to experience severe symptoms, hospitalization and death, according to Harvard Medical School, especially if they receive a booster shot.

"It's not a worst-case scenario, where the vaccines are ineffective," Gronvall said. "In lab scenarios, we've seen, vaccines provide less protection. That seems to be borne out in reality, but we can't project yet into the real world."

3. Will there be more variants that are dangerous, like delta and omicron?

Viruses constantly mutate. Sometimes these mutations emerge quickly and disappear, and other times, they persist and create spikes in the rate of infection and disease. In two years, COVID-19 has mutated into five "variants of concern," according to WHO, based on the severity of disease, the effectiveness of medical countermeasures and the strain's ability to spread from person to person.

The alpha, beta and gamma variants were all downgraded to "variants being monitored" in September, with delta and omicron still considered variants of concern. In January, federal health officials declared the omicron variant the dominant strain in the US, accounting for nearly three-quarters of new infections.

Omicron may be less severe than delta, which doubled the hospitalization rate of the original alpha strain, but is also far more contagious.

By February, the new variant's surge declined, but an even more contagious subvariant -- known as omicron BA.2 -- has been identified. It appears to spread about 30% more easily than the original.

Health officials warn that the longer the pandemic lasts and the longer large groups remain unvaccinated, the more time the virus will have to spread and mutate. While can they map and identify variants, they need time to see how dangerous a new strain is as they gather data on hospitalizations and deaths.

"We're still not great at looking at new variants and projecting what that means in the real world," Gronvall said. "We have better tools [with which] to read genetic material and determine when variants emerge. But we can't read them like a book."

Researchers with the WHO's investigative team arrive at the Huanan Seafood Market on Jan. 31, 2021.

4. Why does COVID-19 make some people seriously ill, including with long COVID?

We know the virus can cause symptoms ranging from headaches, chills and fever to disorientation, nausea and vomiting -- and even loss of taste or smell. While scientists continue to piece together who is more likely to get hit with these outcomes, they still lack answers about why some experience serious illness and others don't.

Age is definitely the biggest correlation for severe disease, Gigi Gronvall, a senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, told CNET. "But there have been 29-year-olds who have died, children who have died, when all indications suggest they should have had a mild disease course."

Scientists are also trying to understand "long COVID" -- a range of symptoms that can begin weeks or even months after a patient is first infected.

The World Health Organization has issued a definition that includes a laundry list of lingering symptoms that include fatigue, trouble breathing, anxiety, kidney issues, blood clots and "brain fog."

But even now, the condition's cause is not clearly known. And the list of symptoms keeps changing.

"After two years, we don't understand much about long COVID, and don't know its prevalence with omicron after vaccination," Bob Wachter, the chair of the department of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, tweeted Wednesday. "It remains a hardship for millions and a lingering concern for me as I think about the prospect of getting even a 'mild' case of omicron."

While some general symptoms, like loss of smell and taste, appear less common with omicron, Gronvall said, "We just don't know if people with that variant will suffer long COVID. We just haven't had enough time to tell."

5. Where did COVID-19 come from?

Experts are still not certain how COVID-19 emerged. The prevailing theory is that it leaped from an animal to a human. The first symptoms of COVID-19 were reported in Wuhan among people who either worked or lived near Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market, an open-air "wet market" selling fresh beef, poultry, fish and produce.

According to numerous sources, including a June 2021 study in Scientific Reports, the market also traded in exotic animals as pets and food, including badgers, hedgehogs, civets and porcupines.

Others, however, claim that SARS-CoV-2 emerged in a lab -- with a naturally occurring or human-engineered virus infecting a researcher, who spread it to others. While there has been no solid evidence for this, former President Donald Trump and his supporters pushed the lab-origin theory through 2020.

"People are looking to blame [someone]," Gronvall said. "They're not looking for an explanation that is very human and plausible. But there's no virus that's been identified in the laboratory that's at all close to what ended up spreading around the world."

Also, Grovnall said, "There's a lot of people using this as a vehicle for other agendas." However, she said, "certainly the Chinese have been lying" about at least one other thing: Government officials originally claimed that there were no contraband animals present at the market, she said, but researchers looking for a separate tick-borne disease photographed many illegal animals there, "stuffed together in close quarters, in poor health and stress conditions, in the months before cases were identified."

Inspectors at the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market in Wuhan, China, which was permanently closed on Jan. 1, 2020.

Because the Chinese government quickly shut down the Huanan market -- and removed all evidence almost as soon as cases of COVID-19 were being associated with it -- researchers are not likely to ever find the exact animal culprit, Gronvall said.

"It wasn't like SARS in 2003, when you had these palm civets there that were all infected and it was a pretty quick thing," she said.

To uncover more about the emergence of COVID-19, President Joe Biden directed the US intelligence community in May 2021 to "redouble their efforts" to investigate the virus' origins.

As we continue into the third year of the pandemic, what we do know is there are many tools at our disposal, including vaccines and antiviral pills, that we didn't have when we first learned of COVID-19.

For more, here's what we know about the omicron variant, what we know about treating long COVID and whether you can still be considered "fully vaccinated" without a booster shot.