Why You Can Trust CNET

Why You Can Trust CNET Everything about how we access and listen to music has changed in the past 25 years

The music industry has been rocked by technology since CNET's start in 1995 and so has how we discover, create, collect and listen to it.

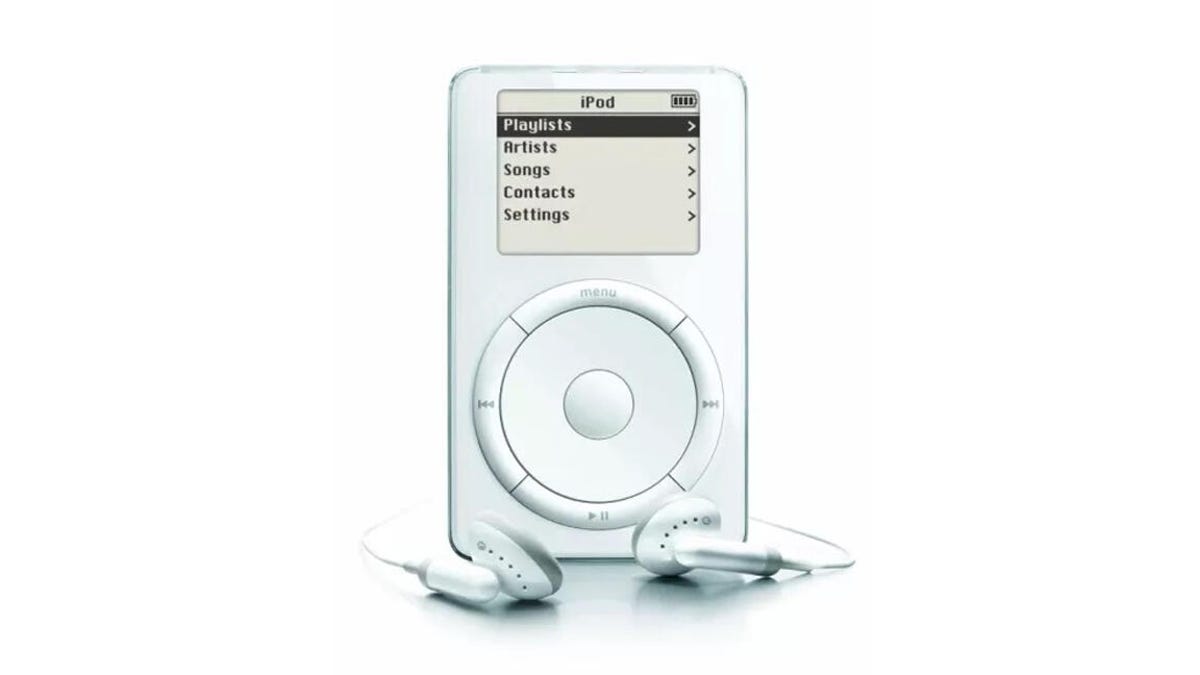

The first-generation iPod wasn't the first digital music player, but it's the most important.

I start just about every morning by shouting, "Hey Google, stream SiriusXMU," at the Google Nest Mini clipped to my kitchen wall. I could just as easily ask it to play any number of artists, albums, songs or playlists, stream an internet radio station from anywhere in the world, or let algorithms generate an instant "station" that fits my mood. As a music lover and collector, I finally have the endless jukebox of my dreams made possible by a slew of streaming services, an inexpensive smart speaker and high-speed wireless internet.

When CNET started 25 years ago, none of those things existed. Looking back today, it feels like they all appeared overnight. But it took a host of technological advances, lawsuit after lawsuit after lawsuit and the reluctant cooperation of music labels and musicians to get us to a point where the world's largest music collections are no further away than an app on your phone, and every playlist is custom-made for your tastes. Here's a brief look back at how it all happened.

From CDs to streaming

In 1995, CDs were the main music media format, surpassing vinyl sales at the end of the '80s and cassette tapes by 1993. At the time, though, if you wanted to make a custom mix or make a copy for your friends, you were still doing it to cassettes. Just two years later, that would start to change.

A Napster screenshot from 2001.

Oddly enough, the CD's digital format hastened its own downfall. By the late 1990s, the prices of computer CD-ROM drives had dropped and software for extracting audio from CDs and converting it into WAV and MP3 files -- aka ripping -- was readily available. CD-R drives that allowed you to create your own audio discs were pricey but attainable. By the end of the decade, you could easily set free the music once trapped on CDs and, perhaps more importantly, share it with others around the world via not-entirely legal peer-to-peer sharing networks like Napster.

Napster would eventually be sued out of existence by the recording industry in 2001, filing for bankruptcy the following year. But the MP3 and the service changed the music world forever. Legal MP3 download sites like eMusic started popping up as well, and Rhapsody launched as the first on-demand music streaming service just after the turn of the century. In a peculiar twist, even Napster lives on in a way. Its brand has traded hands a few times since it was shut down and was most recently resurrected for the name of Rhapsody's current music-streaming service.

Before streaming services really took hold, though, people continued to buy CDs and downloads, the latter getting a huge boost from Apple's iTunes store, which launched in 2003. Rather than risking industry lawsuits, Apple succeeded by inking deals with five major record companies to sell DRM-protected AAC audio files for 99 cents a track and $9.99 an entire album.

The DRM devil

DRM stands for digital rights management and anyone who's downloaded music before 2009 knows what a pain it can be. At its most basic level, DRM puts restrictions on how you can use a digital file that you own. In the heyday of Apple's iTunes Store, the company sold AAC audio files protected with its FairPlay DRM, which restricted playback to its iPod music players and iTunes. Along with limiting what you used to play them, the files couldn't easily be shared on P2P networks. In 2007, Apple started selling premium AAC music files without DRM, and by 2009 it had gone DRM-free. The only rub there was Apple tacked on a charge of 30 cents per song if you wanted to have the FairPlay DRM removed from tracks you'd already bought.

Of course, Apple wasn't alone here, with Sony BMG's rootkit fiasco likely the most notorious DRM overreach of the era. If you played certain CDs from the music label on your computer, it would secretly install copy-protection software stopping you from copying the music. The software was also difficult to remove, and even the uninstaller created security issues for users.

By 2008, Apple would be the largest music seller in the US, but streaming was still wide open. Streaming services and stations continued to multiply during this time, starting with the likes of Pandora (now owned by satellite radio and streaming service SiriusXM) and Last.fm, which is owned by CNET's parent company ViacomCBS and no longer streams music. 2008 also was the year Spotify launched in Europe and grew quickly, thanks to a free-music model for anyone willing to put up with some ads between songs. The service wouldn't be available in the US until 2011, but in no time it became the leader, while competitors like MOG and Rdio were gobbled up by other services. Spotify currently has more than 130 million subscribers.

And, just to put a bow on the CD's downfall in the past 25 years, vinyl, a format that never died thanks to its devoted audience, in 2019 started outselling the CD for the first time since 1986.

Listen up

The evolution of music formats also changed how, where and when we listened to music. In 1995, you may have had a portable CD player and a fat wallet of discs that you carried with you. Or maybe you saved that for your car along with a cassette adapter that let you send audio from your CD player to your car's cassette deck. For listening at home, you'd have individual hi-fi components or a shelf system with a multidisc changer.

As music collections shifted from physical media to MP3s, you likely spent more time listening to music through your computer's speakers or connected headphones at home. The portable CD player was now in a drawer, replaced with one of the first MP3 players. Although, you may have been indifferent to portable players until the first iPod arrived in 2001.

Within a few generations of the device, the iPod would become all the music system most people would need at home, in the car or on the go. At least until the first iPhone was introduced in 2007, which ultimately cannibalized its single-purpose predecessor. Just as the iPod wasn't the first digital music player, the iPhone wasn't the first smartphone, but it was the ultimate always-connected MP3 player we knew only Apple could make.

MP3 players and the iPod haven't completely disappeared yet. Every once in a while a new one shows up. But for most of us, our phones are used just as much for music as they are for sending texts, getting directions, taking photos and scrolling through social media. A phone's wireless capabilities not only allowed us to directly download tracks over the air instead of a wired connection to a computer but also made it possible to trade in big, stationary speakers and iPod docking stations for portable Bluetooth speakers in all shapes and sizes.

And now here we are, able to ask AI digital assistants to play whatever music we want through a web-connected speaker or TV or, hell, even a lamp. You can have it play in a specific room or send it throughout your entire house. Plus, with little to no effort, that music can follow you from your home to your car to the gym to the office or wherever else you go.

A creative boom

How we access and listen to music changed dramatically in the past 25 years, and so has music creation and production. Home recordings are nothing new, but the sheer amount of technological tools made available to musicians over the past couple of decades is staggering.

We have laptops that are as powerful as desktops, but weigh less than 5 pounds and can run digital audio workstations like Ableton Live and Image Line FL Studio, which started as Fruityloops back in 1997.

A singer can cut a vocal track to their iPhone, clean it up or add effects on a tablet or laptop, and then share it with bandmates living anywhere in the world so they can record their parts in the same way -- an entire song created without anyone stepping into an actual studio. Distribution has changed entirely, too, with artists able to go straight to consumers on sites like SoundCloud and Bandcamp.

From listening to looking

In the middle of writing this story, I was reminded of another I wrote for Computer Shopper magazine back in 2005 (which was then owned by CNET) about how to turn an old desktop computer into a digital jukebox -- complete with a $500 15-inch touch-screen monitor that let you explore your music collection without a keyboard and mouse or remote control.

Just five years later, the first iPad was released. Apple basically made my bulky, expensive weekend project obsolete, essentially putting the same touchscreen access to your music into something you could hold while sitting on your couch -- all for $500. That first iPad wasn't immediately ideal for music fans, especially with only 16GB of storage and no wireless syncing. Still, it wouldn't be long before faster wireless and cloud-storage services including Apple's iCloud with iTunes Match would let you have all your music anywhere and literally at your fingertips.

Our physical and digital collections have been supplanted by streaming services tied to connected devices instead of a traditional stereo system. Like I said at the start, between services and a smart speaker (and my phone), I have a never-ending jukebox wherever I am. So where do we go from here?

For starters, the wireless hand-off from device to device could stand to be a little more seamless, not to mention device agnostic. It's wishful thinking that you should be able to pick your source of choice and have it jump from smart speaker to your car to your phone and back again without shouting commands and certainly without connecting cords. Also, with unlimited mobile data plans and the eventual widespread availability of ultrafast 5G networks, it would be great if better audio quality was available regardless of service.

One more thing: After being able to see a lot more live music streamed during the coronavirus pandemic, it seems the next phase of music might be as straightforward as leaning more into video. Obviously, there is plenty of video being made for music, but it's all scattered among various YouTube channels, web sites and services. The future might be in offering streams of live performances from different venues, big and small, around the world or even from artists' homes, so you can watch it on your TV, tablet, computer or phone as it happens or stream it later as video or audio. Seattle-based startup Lively tried something similar in 2014 as a way to curb people from recording concerts with their phones, but maybe now is the right time to make something like this happen.