Thousands Possibly Exposed to Measles in Kentucky, CDC Says

A large spiritual gathering last month is connected to a case of measles, according a health alert. Here's what to know about the disease.

People who attended the spiritual revival in Wilmore, Kentucky, on Feb. 17 and 18 might have been exposed to measles, according to a Friday alert from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

An unvaccinated person who came down with the illness attended the Christian revival at Asbury University on those dates while infectious. The CDC estimated that about 20,000 people were at the event during this time, and an "undetermined number" of them might have been exposed to measles. Health care providers should be "on alert" for cases and symptoms of measles, which include a rash, fever and cough.

People who were at the event that week should also monitor themselves, especially if they aren't vaccinated against measles, according to Kentucky health officials.

"Attendees who are unvaccinated are encouraged to quarantine for 21 days and to seek immunization with the measles vaccine, which is safe and effective," Dr. Steven Stack, commissioner of the Kentucky Department for Public Health, said in a news release last week.

The CDC says the incident highlights other recent measles outbreaks and the importance of early detection in curbing the spread of the highly infectious disease. In late November, the CDC and the World Health Organization warned about a huge disruption in child measles vaccinations. Nearly 40 million children worldwide missed their measles vaccine in 2021, the health agencies said.

Measles has been considered eliminated from the US since 2000, which means that while there have been isolated outbreaks, there hasn't been "continuous transmission of the disease for more than 12 months," according to the CDC. In the decade before 1963, when the measles vaccine became available, 3 million to 4 million people were infected and 48,000 were hospitalized per year.

There's a smattering of measles cases each year in the US, with small outbreaks sometimes occurring in communities with lower than normal vaccination rates. And while vaccinated children and adults have little to fear when it comes to measles, lapses in vaccine uptake and concentrated outbreaks once again call attention to what happens when infectious diseases find an opportunity to spread. In recent months in Ohio, for example, there was an outbreak of measles concentrated among unvaccinated children. Close-quartered holiday get-togethers and religious gatherings, for example, provide ample opportunities for infectious diseases to spread.

Ross Kedl, professor of immunology and microbiology at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, said that it's "not a coincidence" that the Ohio measles outbreak was concentrated among unvaccinated children.

"If it finds itself in a susceptible population and the right circumstances -- which the holidays present quite nicely -- it can grow pretty quickly," Kedl said.

Here's what to know.

What is measles and what are the symptoms?

Measles is a highly contagious, airborne disease that causes fever, a red rash, a cough and red eyes. It's so contagious that as many as 9 in 10 people who don't have protection (either through vaccination or prior infection) will get it, according to the CDC.

Symptoms typically appear between seven and 14 days after an exposure, and the rash will follow three to five days after the first symptoms, according to the CDC.

Many people are at risk for complications from measles, including young children under age 5, adults over age 20, those who are pregnant and people with compromised immune systems.

Dr. Steven Abelowitz, medical director of Coastal Kids pediatric medical group, says that severity-wise, measles is "significantly higher than most viruses we're exposed to."

According to the CDC, about one in five people who are unvaccinated and get measles will be hospitalized.

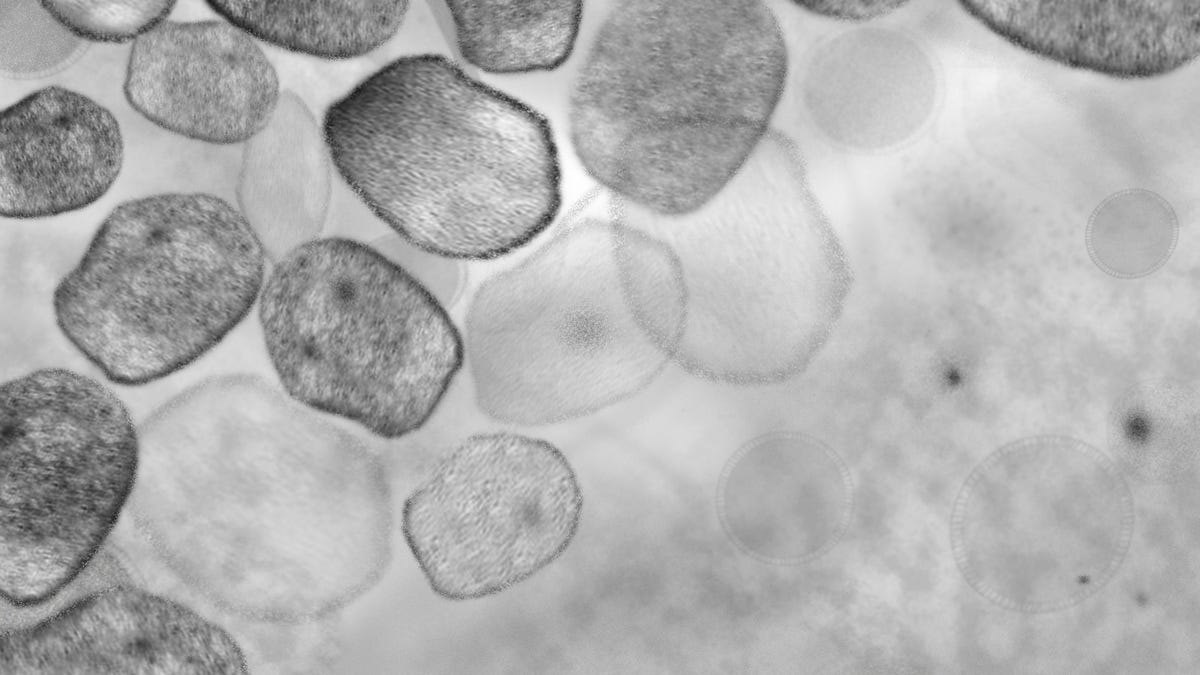

An example of measles after three days with the rash.

About the measles vaccine

Vaccination against measles is either covered by the MMR vaccine or the MMRV vaccine. Both protect against multiple diseases including measles, mumps and rubella, but MMRV includes varicella too, which is the virus that causes chickenpox. For a complete comparison between the vaccines, check out this chart from the CDC.

The American Academy of Pediatrics and the CDC recommend that all children get two doses of the measles vaccine: one shot at 12 to 15 months, and another one at 4 to 6 years.

Most people in the US have been vaccinated against measles. This protection is considered lifelong: one dose is about 93% effective, and two doses are about 97% effective, with a range of 67% to 100%, per the CDC. If you weren't, or you're unsure of your vaccination record, reach out to your doctor. You may get another MMR vaccine dose if you don't have documentation, according to the CDC.

And if you were born before 1957 -- regardless of your vaccination status -- you also have measles protection in the CDC's eyes, because you probably had it as a child.

What you can do about it

Vaccinated adults should have very little to worry about in regard to measles. However, if you live in an area with a confirmed measles case, or if you've traveled internationally, you can reach out to your health care provider if you're worried about your risk.

But if you're the parent of a young child who missed one or both doses of the measles vaccine, contact your pediatrician as soon as you can.

This applies not only to children in the US, but to people living in all countries.

"For three years, we have been sounding the alarm about the declining rates of vaccination and the increasing risk to children's health globally," Ephrem Tekle Lemango, UNICEF's chief of immunization, said in a November news release. "We have a short window of opportunity to urgently make up for lost ground in measles vaccination and protect every child. The time for decisive action is now."

According to Kedl, the Ohio outbreak over the winter was "consistent with the next step of things" when measles vaccination rates continue to wane, adding that "the next thing that will likely happen is you'll see an increased frequency of outbreak."

"This is not a problem that needs a solution," Kedl said. "This is a solution in need of acceptance."