When zeppelins ruled the skies (photos)

Road Trip 2011: The Zeppelin Museum in Friedrichshafen, Germany, is a treasure trove for airship lovers.

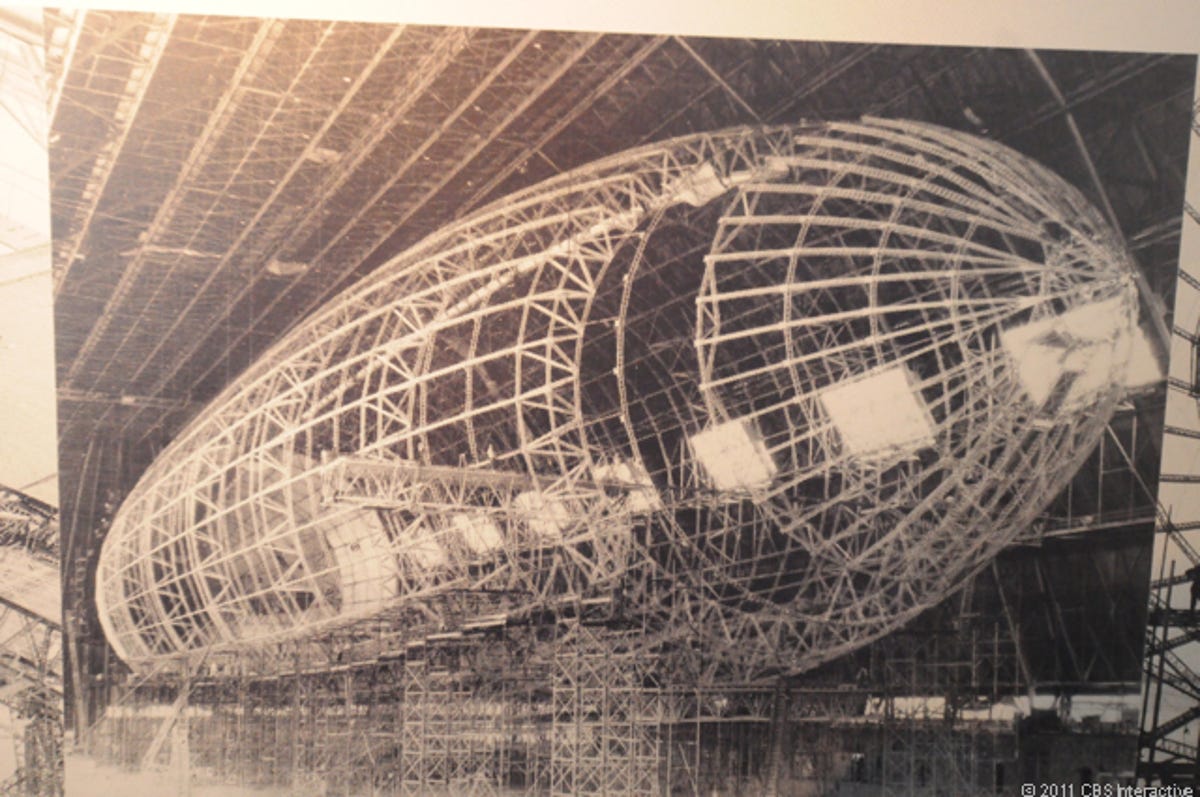

Zeppelin structure

FRIEDRICHSHAFEN, Germany--It seems an odd place for a museum celebrating the history and achievements of an aerial innovation, but right on the shores of Lake Constance here is the Zeppelin Museum, an homage to Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin's airships.

Of course, once you enter the museum, you realize it's not a strange place at all--in fact, the world's first zeppelins were created here, and many, including the most famous of all, the Hindenburg, were based right here in Friedrichshafen.

There were 119 zeppelins built in the first half of the 20th century, and 130 were planned. Today, those German zeppelins are no more, but they live on at this great little museum.

Here, we see a photograph in the museum of the construction and interior structure of the Graf Zeppelin, one of the greatest of the early airships.

Zeppelin model

This is a scale model of a zeppelin at the museum, with a cut-out section showing some of the infrastructure inside, including the water tanks, the small tanks on the bottom. This model also shows two of the five gondolas on the zeppelin.

Hindenburg size comparison

Before the disaster, the Hindenburg was a famous attraction in its day. On May 6, 1937, it exploded in Lakehurst, New Jersey. The Hindenburg was 245 meters long, the longest flying vessel ever, and its size is seen here in comparison to the size of the Zeppelin Museum.

Construction ladder

This is the original construction ladder used for maintenance on the Hindenburg.

Scale Hindenburg hangar

This is a scale model of the Hindenburg's hangar. Having seen the ladder in the previous picture, the size of the ladder in this photograph gives a better sense of the scale of the hangar, and the Hindenburg itself.

Restroom

This is a replica of one of the restrooms aboard the Hindenburg. Passengers aboard any airplane today would not feel this bathroom was decades old.

Bedroom

This is a replica of one of the bedrooms on the Hindenburg. Though it was a giant airship, it originally carried just 72 passengers.

Interior structure

This is a giant, real-size replica of some of the interior structure of the Hindenburg.

In and out of the hangar

These are photos from the Zeppelin Museum of the Hindenburg both inside and outside of its hangar. Because of the wind that blew strongly at Lake Constance, perhaps the most dangerous maneuver of all for a zeppelin like the Hindenburg--prior to its explosion--was being towed in or out of the hangar. The wind was capable of smashing the airship against the walls of the hangar.

Gondola

This is one of the original five gondolas from the Graf Zeppelin, otherwise known as LZ-127. The gondolas hung on the lower sides of the zeppelin, and a crew member would work there for about four hours. The task of driving the zeppelins was so taxing--partly because temperatures could reach 122 degrees Fahrenheit-- that each pilot could only work about four hours before being relieved. New pilots were brought in even as the zeppelins flew through the air.

Daimler-Benz motor

This is an original Daimler-Benz zeppelin motor.

Count Von Zeppelin

A bust of Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin, as seen at the Zeppelin Museum in Friedrichshafen, Germany. The count was given a large grant from the King of Wurttemberg to build his original zeppelins. Many people thought he was crazy until his creations were the toast of the world. Then they thought he was a genius.

Hindenburg lounge

This is a replica of the lounge aboard the Hindenburg.

Hindenburg reading room

This is a replica of the reading room aboard the Hindenburg. Note the mailbox on the left wall. Many passengers sent postcards while aboard, but the postage was so expensive--since the airship could deliver mail in just a few days versus the amount of time it took by ship--that most of the costs of a zeppelin flight were paid for from this postage.

Hindenburg propeller

This is a propeller from the Hindenburg.

First zeppelin

This is a scale model of the world's first zeppelin. Launched for the first time in 1900, this early airship was far smaller than the Hindenburg and was made using a design that allowed the zeppelin to flex in heavy winds.

Floating hangar

While most of the later zeppelin hangars were built on solid ground, some early ones were constructed over water. The idea was that the hangar could be oriented into the wind, allowing for the zeppelin to be pulled out of or put back inside the hangar without the wind fighting the operation, and potentially threatening to destroy the airship.

Disaster medallion

This is a medallion commemorating the destruction of the Hindenburg in 1937.

Newspaper

Seen here is a newspaper reporting the destruction of the world famous Hindenburg.

Wine list

This is an original wine list from the Hindenburg.

Radio

This is an original radio from the Graf Zeppelin.

Zeppelin with swastikas

This is a replica of LZ-130, the Graf Zeppelin, which was adopted by the Nazis for propaganda use during the 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin. Count von Zeppelin said that he would allow his airships to be used by the Nazis even though he didn't approve of their politics. This may partly explain why Hermann Goering, a senior Nazi leader, was opposed to the zeppelin program and demanded that the last of the airships be dismantled so the Nazis could use its aluminum in the World War II war effort.

Military hat

This is a hat worn by a Germany military official aboard one of the military zeppelins.

US Navy zeppelin on a ship

Though Germany fought against the United States in two world wars in the first half of the 20th century, the U.S. adopted the zeppelins, and one was even launched from a U.S. Navy ship, as seen here in this archival photograph.

Zeppelin over New York

Seen here is a U.S. Navy zeppelin over New York.

Spy plane

For a time in World War I, the Germans used zeppelins to conduct reconnaissance missions. They would fly the airships high above the clouds and then drop these small vehicles down from the zeppelins on rope, allowing the occupant to keep tabs on what he saw below.

Macon

This is a replica of the U.S. Navy zeppelin, the Macon. It was based at Moffett Field in Mountain View, Calif., before the airship crashed off the California coast in 1935.

Venice biennale

For the 2009 Venice biennale, artist Hector Zamora created a whole series of artworks depicting the fictional arrival of a group of zeppelins in the famous Italian city. Some people saw the photos and thought there were actually zeppelins dominating the skies over Venice. In reality it was all computer-generated.

Von Hindenburg

A bust of Paul von Hindenburg, seen at the Zeppelin Museum, in Friedrichshafen, Germany.

Zeppelin china

This is actual china from one of the zeppelins.