Take a look at Zipline's new drone delivery system

The startup's technology vaults airplane-like drones into the air then snatches them back when they return from delivering medical supplies.

Zipline drone launch

In Yolo County, California, startup Zipline has begun testing its second-generation drones with dozens of flights each day. The drones are already in use delivering blood to hospitals in Rwanda, but Zipline hopes to expand to other countries and other medical supplies.

Zipline drone

The Zipline second-generation drones have a 10-foot wingspan.

Zipline drone repair

Zipline technicians repair a drone wing. The wing is modular and can be easily replaced.

Zipline drone package drop

A Zipline drone drops a test package over a test site on a ranch in Northern California. Here you can see the dual propellers atop the drone.

Zipline drone package parachute

A Zipline drone delivery package descends by parachute to the ground. Zipline can land it on a patch about the size of two parking places.

Zipline drone catcher

Zipline's system flicks a cord up to catch a hook at the back of a passing drone to snatch it out of the air. The cord pays out to decelerate it then winds back in to lower the drone like a caught fish.

Zipline drone launcher loading

Two technicians place a 45-pound Zipline drone on its launch system. Zipline launches dozens of tests flights every day.

Zipline drone midflight

A Zipline drone flies over the hills and trees of Yolo County, California.

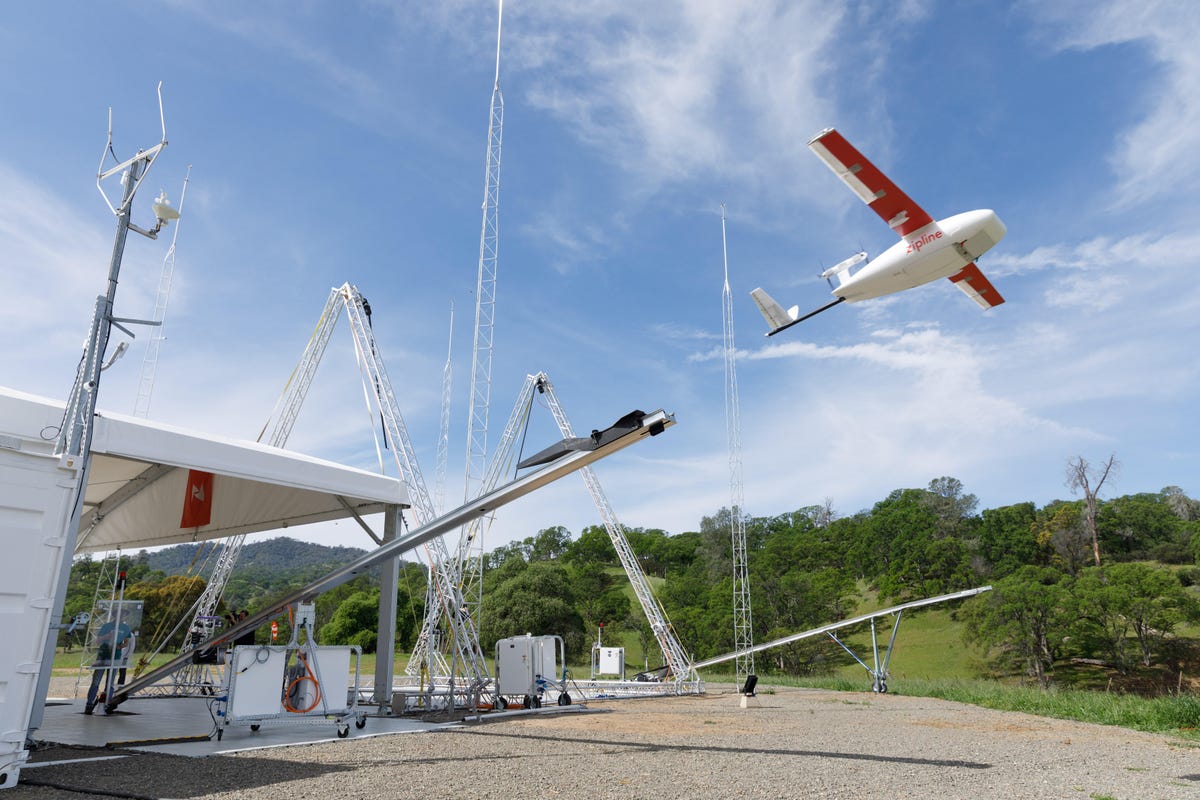

Zipline drone midlaunch

An electric motor winds a cable that slings a Zipline second-generation drone into the air in Yolo County, California.

Zipline drone wing

Zipline drones are designed to fly at night and in the rain. They integrate with air traffic control systems and are equipped with blinking lights like ordinary aircraft.

Zipline battery charging

After each flight, a Zipline drone's battery and electronics package is placed into a rack for recharging. It takes about five battery packs to operate two drones continuously.

Zipline battery pack

A Zipline drone battery and electronics package. They use the same battery cells as a Tesla car.

Zipline battery loading

Zipline's second-generation drones have a compartment for easy installation of a new battery and electronics module before each flight.

Zipline payload loading

The Zipline drones have a compartment that accepts a payload about the size of a cake box and weighing up to about 4 pounds.

Double Zipline drones

Zipline flies its drones in looping test flights over a quiet ranch in the Central Valley foothills.

Zipline drones fuselage

The Zipline drone fuselage is sculpted into a teardrop shape from lightweight styrofoam.

Zipline coordination

Dan Czerwonka, head of global operations for Zipline, communicates with the startup's base station by walkie-talkie.

Zipline drone launch site

Zipline's test site in Yolo County, California, consists of a storage container, a couple of temporary buildings on a graded gravel patch, and the aluminum struts of the launch and capture systems.

Turkey vulture

Drones aren't the only flying objects at its Northern California ranch site. Here a turkey vulture soars over the hills and fields.

Zipline drone package drop

A Zipline drone drops a test package over a test site on a ranch in Northern California.

Zipline drone wing

A 10-foot Zipline drone wing goes into the shop for maintenance.

Zipline drone dual motors

Dual propellers move the drone at speeds up to about 80 mph. If one motor fails, the drone will still fly on a single one, and during cruising only one is used.

Yolo ranch hillside

The rolling hills around Zipline's test site is surrounded by oak trees filled with acorn woodpeckers and fields filled with western meadowlarks. In summer after winter rains stop, much of the green fades to brown and yellow.

Zipline launcher lightning protection

Zipline's test site is equipped with four towers topped with a fuzz of wires to dissipate electrical charge and reduce lightning risks.

Zipline drone

A view of a Zipline drone from the rear.

Going to Zipline dropoff site

It's a 10-minute drive on dirt roads to reach the site where Zipline's drones drop test packages.

Zipline drone QR codes

Zipline drones have QR codes; a smartphone app scans them in a process that begins a drone self-test of its different systems.

Zipline drone near miss

Zipline tries out new software at its Central Valley 's test site, and drones don't always snag the cord that's supposed to stop their flight. If they miss, they buzz around in a circle for another attempt.

Zipline drone launch site

Zipline stores old drones in a white shipping container.