Climate change gets artsy (images)

Batik artist Mary Edna Fraser paints images of melting glaciers and shifting coastlines on silk to make beautiful, and sometimes sobering, creations.

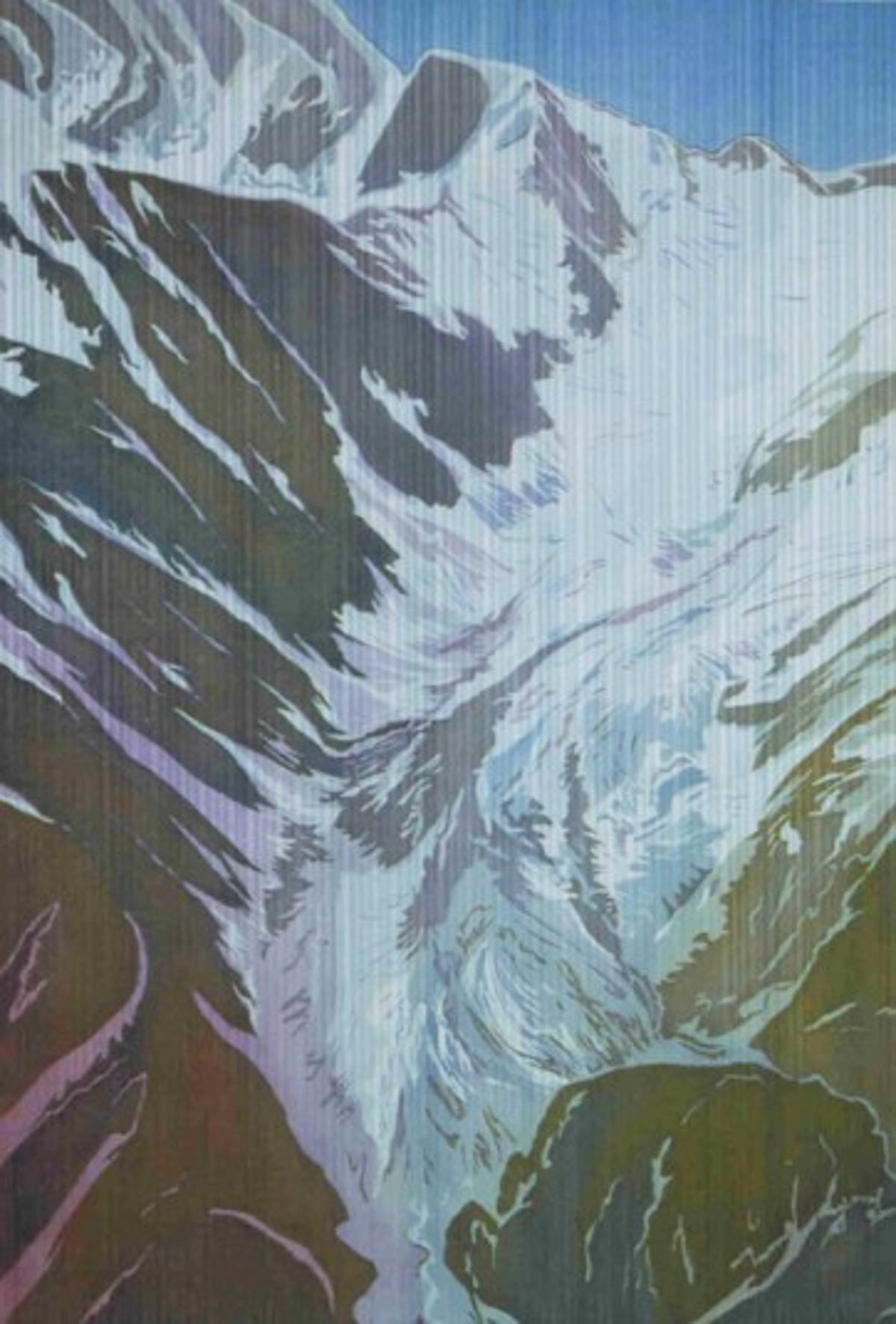

Glacial Canyon (Alaska)

Artist Mary Edna Fraser captures the beauty and fury of nature in hand-dyed silk batiks based on maps and charts; her own aerial photographs and memories of flight; and satellite and space imagery.

Her works depict everything from vibrant celestial portraits to the geological impact of such earthly disasters as Hurricane Katrina and the Gulf Oil Spill. She has also created numerous batiks of barrier islands, river deltas, mountains, and glaciers, sometimes depicting the ways global climate change threatens those landscapes.

Many of her climate change-themed canvases will be on display through November 6 at the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences in Raleigh. They're part of the exhibit "Our Expanding Oceans," which explores the major elements of global climate change, from melting ice to rising seas, through both art and science.

The exhibit is a sort of artistic companion piece to the book "Global Climate Change: A Primer," which was co-authored by geologist Orrin Pilkey and his son Keith, and which also features some of Fraser's creations.

Alpine glaciers could raise the sea level by 1 to 2 feet if they all melted, scientists say. "Glacial Canyon," pictured here, measures 60 inches by 36 inches, and is Fraser's tribute to the beauty and drama of glaciers as exemplified by the Triumvirate Glacier northwest of Anchorage.

"Current impacts of global change stir my scientific and artistic interest," the artist says.

Saint Louis 1988 & 1993

To make batiks, removable wax is applied to fabric, creating areas that will repel dye while unwaxed areas absorb it.

This batik, titled "Saint Louis 1988 & 1993," shows the junction of the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers near St. Louis in 1988 (left), and again during the flood of 1993. Increased extreme-rainfall events are likely to become more frequent because of global change, according to geologist Orrin Pilkey, a Duke University professor emeritus of geology.

To research this piece, Fraser flew over the site in a jet and spent time on the ground by the rivers' edges. The city of St. Louis is indicated in red.

Great Barrier Reef II (Australia)

Australia's Great Barrier Reef, as well as other coral reefs around the world, are threatened by warming water, ocean acidification, and rising sea levels, studies show. Human impacts on the reefs and the marine species that inhabit their ecosystems include pollution, mining, and burial by beach-replenishment sand.

Fraser says this 104x45-inch batik synthesizes her experience with underwater photography, which she likens to "flying under water, with colors and shapes constantly in motion."

While some of the artist's works capture the impact climate change has already had, others try to call attention to natural resources that could be lost as a result.

Boston II

Greater Boston, with a population of about 4.5 million, is located at low elevations and is thus highly vulnerable to rising sea levels, says Pilkey, who adds that cities will likely have to abandon low-lying portions and build seawalls and tide gates to protect against rising waters.

According to a U.N. study, other highly vulnerable low-lying cities include New York; New Orleans; Tokyo; Rotterdam, Holland; and Virginia Beach, Va.

In the same study, the U.N. urged cities and national governments to consider threats posed by environmental degradation and global warming in their urban planning and to come up with innovative ways to address the changes.

Bhutan's Himalayas

The Himalayas--called the "water tower" of Asia because the rivers emerging from them provide water to upward of a billion people--contain the largest mass of ice outside the polar regions. But they are retreating at a distance of 100 to 150 feet per year, Pilkey says.

Bhutan, whose Himalayan mountain range is pictured in this 37.5-inch by 54-inch Fraser batik, is a world leader in planning for global change, he adds. The country has plans in place to move small villages threatened with the loss of drinking water supply caused by melting Himalayan glaciers.

The National Science Foundation and National Academy of Science have featured Fraser and Pilkey's collaboration, as have the Duke Museum of Art and Emory University.

Kilimanjaro (Africa)

The snows of Africa's Mount Kilimanjaro, made famous in Hemingway's short story of the same name, are disappearing, Pilkey says. This small, rare tropical glacier atop the mountain currently stands 19,340 feet tall, but it is rapidly shrinking. In Fraser's silken aerial view, clouds shroud the iconic Kilimanjaro peaks.

Fraser often develops potential color palettes for her batiks on location.

Selenga Delta (Lake Baikal, Russia)

Fraser's work has been widely exhibited at venues including the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum, the National Academy of Sciences, and the National Science Foundation.

Much of her aerial imagery is shot with Nikon digital cameras from the open windows of her grandfather's vintage 1946 Ercoupe plane with her father or brother as pilots. This batik of the Selenga Delta in Russia's Lake Baikal, however, was her first to be created using Google Earth as a reference.

Melting of the permafrost on the delta and in this southeast Siberia region will add significantly to the methane concentration in the atmosphere, Pilkey says.

Mouths of the Mekong

Fraser based this 52x47-inch batik of Vietnam's Mekong river on a military map from the Library of Congress. The bloody color of the South China Sea contrasts with the edges of the tropical forests and "resembles a sorrowful, skeleton-faced Buddha," the artist says. Land mines from the Vietnam War still threaten those who remain in this countryside.

Growing human demands on the Mekong Delta, as well as on the Red River Delta to the north, will displace a larger proportion of the population in Vietnam than in any other country, Pilkey says.

Iceberg

Fraser based her 77x44-inch batik called "Iceberg" on a digital composite photograph by Ralph Clevenger. It depicts an Antarctic iceberg weighing approximately 300 million tons; the underwater image was shot in Alaska and flipped upside down.

The art accurately represents the amount of an iceberg that's hidden below the water's surface. Only one-seventh to one-eighth of an iceberg can be seen above water. Thus, the phrase "tip of the iceberg."