Why You Can Trust CNET

Why You Can Trust CNET Facial recognition has always troubled people of color. Everyone should listen

Black and brown communities are often the first to warn about surveillance tech and the last to get recognized for it.

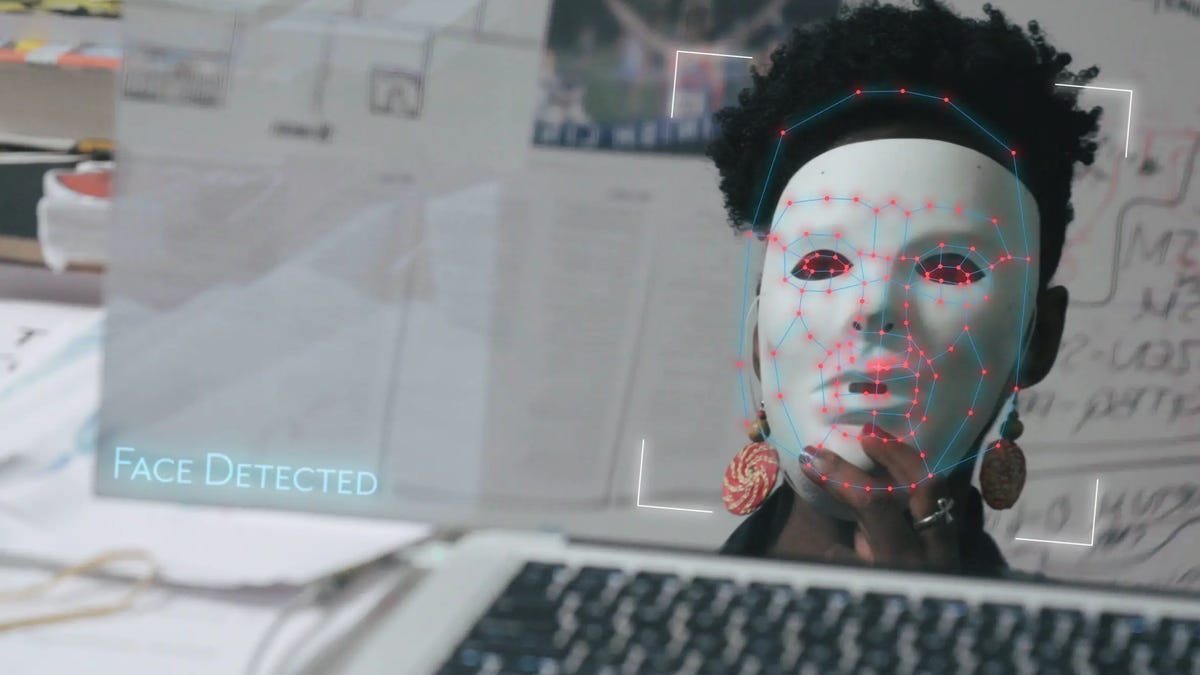

Researcher Joy Buolamwini's face was undetectable by the facial recognition system used in her student project -- unless she put a white mask over it.

When Amazon announced a one-year ban on its facial recognition tools for police, it should've been a well-earned win for Deborah Raji, a black researcher who helped publish an influential study pointing out the racial and gender bias with Amazon's Rekognition.

Amazon called for governments to place stronger regulations on the technology. Nowhere in its post on Wednesday did the company acknowledge Raji's work, which found that Rekognition incorrectly identified women as men 19% of the time.

"For them to write about this moratorium and not reference our work, or the ACLU's work to call them out in the first place, it's just been really frustrating for them to not acknowledge the role of that research," Raji said. "Prior to that callout, they were not saying anything about facial recognition."

Just two days earlier, IBM announced its decision to leave the facial recognition market. The company's CEO, Arvind Krishna, wrote in a letter to Congress that the company was against technology used for racial profiling and mass surveillance, echoing a call that activists have been making for years.

A familiar story starts to emerge: Companies are finally following the advice of experts who have warned about the dangers of bias in facial recognition and broader surveillance technologies.

But they're also failing to credit the people -- many of them from communities of color -- who flagged the problems in the first place. For instance, the concerns about bias didn't just come to IBM out of thin air -- these were issues first brought to light by two researchers, Joy Buolamwini and Timnit Gebru, in a 2018 research paper titled Gender Shades.

The research paper played a major role in steering the national conversation on facial recognition, which now has widespread scrutiny among federal lawmakers and local officials. Amazon was familiar with their work -- the company challenged the research days after Buolamwini and Raji published their findings.

"Whenever they make a stride forward, they almost never mention our names," Raji said. "It's very discouraging to see that and understand that you'll only be named in responses to the problem."

Facial recognition is one of many surveillance issues first raised by black and brown communities, which often don't get proper credit for their impact. CNET spoke with black privacy advocates and researchers who say they've often felt ignored or unheard about surveillance issues.

Citation in academic work is important, but recognition in public advocacy is crucial for attracting future researchers and funding. Beyond that, hearing these voices is critical because they help developers and companies miss blind spots that cause unintended consequences with new technologies.

"What people don't realize is that what that erasure does is it strips us of our collective revolutionary imagination," said Mutale Nkonde, CEO of AI For The People, a nonprofit for educating black communities about artificial intelligence and social justice. "It allows other people to come in and take credit, and it reinforces this story that the only people that can move the world are rich, white men."

Surveillance technology is becoming a mainstream issue thanks to hundreds of protests against police brutality and calls to defund the police since the death of George Floyd at the end of May. The many surveillance tools that police have are being used on protesters -- but for years, have historically been used against marginalized communities.

The shift means that major police reforms, like the Justice in Policing Act introduced by House Democrats, include restrictions on surveillance, like banning facial recognition without a warrant. That policy proposal comes from the work of researchers like Buolamwini, Raji and Gebru, and concerns raised by the communities most affected by this technology.

Groups like Mijente, which fights for Latinx rights, have long called for Amazon to cut its ties to the Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency, raising concerns about how their technology is used to help track and arrest immigrants.

"Historically, marginalized communities have been the most surveilled and have the most harm perpetuated against them because of surveillance," said Chris Gilliard, a professor of English at Macomb Community College who studies institutional tech policy and privacy. "It's not surprising that they are the ones who are most vocal, most active and the earliest to speak out."

Surveillance's racial bias

Brooklyn tenants protesting against facial recognition in May 2019.

Communities of color -- particularly ones in low-income areas -- often serve as testbeds for surveillance technology. And most of that equipment is funded by taxpayers and installed by police in those neighborhoods.

"When you have a technology that is used typically by law enforcement, you're also going to have a higher proportion of black and brown people that are affected," Nkonde said.

In Detroit, police rolled out Project Green Light in 2016, a public-private partnership through which officers had access to real-time camera footage from businesses in the city. The cameras are now in more than 500 locations around the city, which has a population that's 80% black.

Facial recognition is now being offered as a luxury for apartment buildings, but in New York, public housing tenants have lived with facial recognition since 2013. In Brooklyn, tenants like Fabian Rogers and Tranae Moran warded off facial recognition installations for their housing complex.

The two had a personal experience of surveillance technology coming into their homes and are among the first in the country to show that these tools can be pushed back. When their campaign first started, Moran expected their facial recognition concerns would get ignored.

"We're the last people they talk to but the first people they deploy these programs on," she said.

The victory against facial recognition in their apartment building was one of the first times that public pushback against the surveillance tool changed policy. That fight inspired the No Biometric Barriers to Housing Act and showed others that public outcry could lead to changes against surveillance measures.

"It's pretty revolutionary that a community of tenants would get together and say, 'fuck this, this doesn't belong in our living space,'" Gilliard said. "I don't think it'll ever get the credit it deserves for doing that."

Before Amazon's Ring had more than 1,000 police partnerships, it started with a pilot program in a Los Angeles neighborhood where more than half of the residents were minorities.

The video surveillance doorbells and its many partnerships with police have faced plenty of public scrutiny from lawmakers since, but its earliest criticisms come from Gilliard and Nkonde -- many of which had been ignored at the time.

Nkonde recalled a visit two years ago to the house of a friend, who had a Ring doorbell facing visitors. There was a criminal investigation in the neighborhood at the time, and police requested video footage from residents in the area.

She was with her family, including her son, who was pictured in the doorbell's feed. Her friend sent the footage over to police but didn't see what the issue was.

"My friends did not understand why that was problematic, that my child's picture would end up in this database just because he came to the door," Nkonde said. "There was a real explainability problem."

Momentum for change

Despite being the first to recognize and call out issues with surveillance and racial bias in algorithms, Black and brown privacy advocates said they don't feel heard when they raise these issues.

The concerns around surveillance are ringing louder than ever now with calls for police reform, but for a while, many had felt ignored until the arguments got co-opted.

"The black experience involves a lot of bringing up issues that we're personally connected with and watching those issues only be taken seriously once someone outside of us reinforces those ideas in a mainstream way that someone can accept," Raji said. "When you discount the voices of black and brown people who have the most critical points about the risks of the technology, you water down the arguments."

That watering down can look like a one-year moratorium on facial recognition being celebrated when the original push was for a complete ban on the technology. Or a proposed law that calls for facial recognition limits, but only for federal investigations, leaving millions of immigrants vulnerable to identification searches by ICE.

Moran and Rogers felt that watering down happen first-hand. The legislation inspired by their fight against facial recognition would protect people who lived in public housing from surveillance, but there was a key flaw in the policy: Rogers and Moran didn't live in public housing.

"A lot of the times, lawmakers will jump to conclusions on what communities need and then you have policies where everyone thinks there's progress, but when you look at the fine print, they're Swiss cheese," Rogers said. "You need to have conversations with people affected because it's only through people who have experienced these things that you know where the real problems lie."

The calls for surveillance reform could be a hollow victory if the changes don't mean much for the people most affected by the technology. It's not just the policies around facial recognition that need to change, but the voices directing those reforms too, privacy advocates said.

Gilliard said he's found that people don't see the issues with surveillance like facial recognition because they don't feel affected by it. It's often black and brown communities trying to warn about these blind spots. With the momentum behind police reform, there's more hope that people will start to listen.

"You often have to convince people that it's not just someone else getting harmed," Gilliard said. "Even though marginalized communities are hurt more often and more severely at first, a lot of these unjust practices usually don't stop there. It just starts there and branches out."