Inside Ingress, Google's new augmented-reality game

Google reveals a strange new game from its Niantic Labs project this week -- and we're among the first to play it.

Last week we began to see the first hints of Google's first foray into so-called "alternate reality gaming," in which cryptic clues are strewn about the on- and offline worlds for the perusal of highly engaged fans. "What is the Niantic Project?" asked a teaser video. As of today, we know the answer: the Niantic Project is a game called Ingress.

As described in a teaser video, Ingress describes a world in which two shadowy sides are vying for dominance: the Enlightened, who are trying to establish portals around the world that will let them control people's minds, and the Resistance, who are trying to stop them.

The game takes the form of a free mobile app, now available on the Google Play store for Android devices. It is the second product from Niantic Labs, a startup accelerator within Google. Niantic is run by John Hanke, the former head of product management for Google's "Geo" division, which includes Maps, Earth and Local, among other divisions. Niantic's first project was Field Trip, an Android app for discovering the world around you. Released in September, Field Trip sends notifications to a smartphone whenever a person passes an area of possible interest -- a landmark, a park, a highly rated restaurant. In my use, it's been a fun way of exploring new cities and unfamiliar neighborhoods.

With a similar spirit of exploration, I set out today to give Ingress a whirl. The game is currently in a closed beta, but I got an early access code from Google. I downloaded the app and wandered onto the streets of San Francisco looking for some adventure.

Into the wild

Ingress begins with a series of training missions designed to orient new players. Quickly it introduces you to its quirky lexicon. Around town you will find various "portals"; the point of Ingress (at least so far) is to control them. To control portals you have to "hack" them, which is akin to a check-in on Facebook or Foursquare. Hacking portals rewards you with various items, the most important of which are portal keys and resonators. Portal keys allow you to link portals together; resonators power them up and can protect them from being stolen from your rivals. Linking three portals together creates a "field," which is more powerful than a portal, and is apparently essential for world domination.

All this hoofing around hacking portals is hard work, and Google makes you pay for it with something called XM. XM is short for "exotic material," and it shows up on your smartphone screen as a series of glowing blue dots on the street. Walking down the street draws XM to your person, refreshing your health. In my time with the game, I found it to be relatively abundant -- but only in places I hadn't yet visited. The point of XM is to get players to wander down unexplored paths.

After an initial tutorial upon opening the app -- which I received while standing awkwardly on a street corner, gawking at my smartphone like a tourist, getting more than occasional looks of disdain from passersby -- it was time to find a portal. At this point, I should confess that my sense of direction is terrible at best, and so much of my first effort in portal location was spent walking north down one street, doubling back south, and then realizing I was supposed to be walking west the entire time. This is not a complaint about Ingress -- that's roughly my procedure for finding any new address.

But it struck me, as I meandered through San Francisco's South of Market district, that while Ingress gave me a grid of streets to look at, it didn't tell me their names. As a player you appear on the map as a directional indicator, and the indicator spins with you, roughly in real time. But I would have had a much easier time navigating the game if it told me to head for 2nd Street and Mission, say, instead of a blue line that is two blue lines over from my current blue line, which is what Ingress asks you to do.

As you walk, a voice counts down the distance until you reach your targeted portal -- Ingress is a game best played with headphones in. Some of the portals appear tied to landmarks, like San Francisco's Castro Theatre, and some of them seem to appear at random spots on the street. The portals I encountered as I played were all virtual; or at least, I couldn't tell what they were supposed to be tied to. Once I finally found the first one, I "hacked" the portal, triggering a string of training missions showing off various facets of the game. Some portals are booby-trapped, for instance, and hacking them triggers virtual explosions that damage your health. Portals can also be upgraded so that they can link to other portals over increasingly long distances.

Exotic matter, indeed

Portals, resonators, exotic matter -- it can all sound like a lot of hooey, if you are not prone to enjoying science fiction-tinged conspiracy theories. It can also be a lot of information to process, particularly while you are standing on a street corner, keeping one eye on your surroundings lest you be relieved of your smartphone by an opportunistic thief.

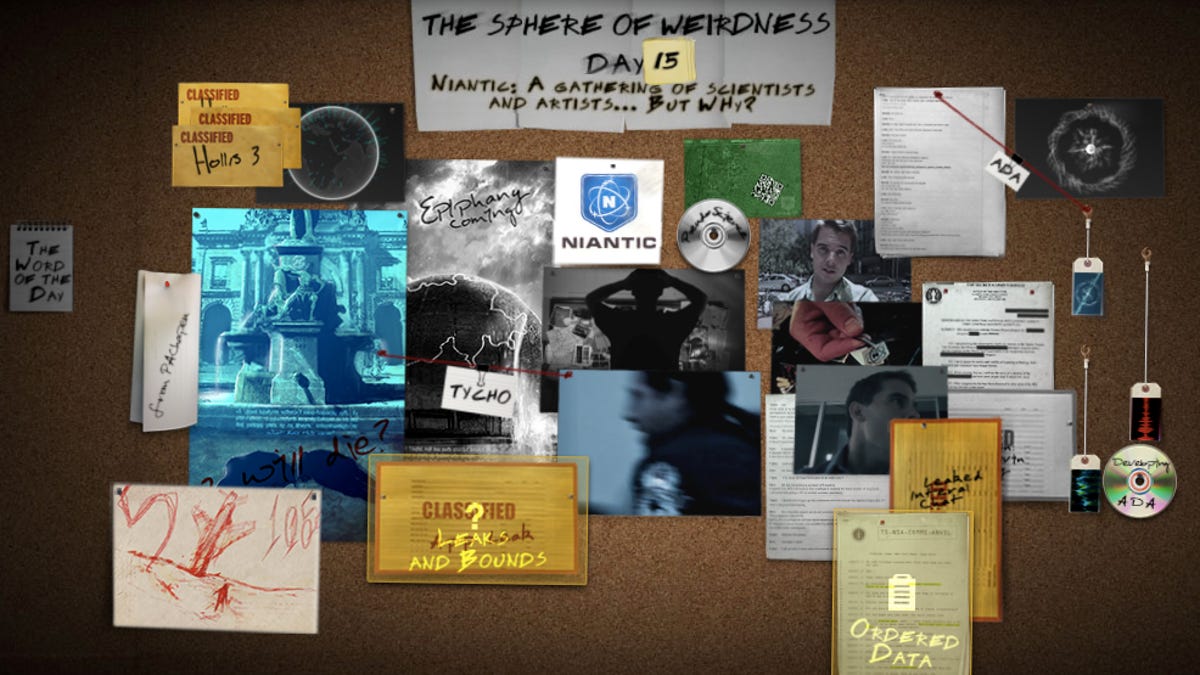

To that end, Google has set up a companion website, the Niantic Project, which contains a virtual cork board full of everything known so far in the in-game narrative. In a nice touch, a slider lets you go back and forth in time; newcomers can dive in at the beginning and see how the game evolved, or skip to the latest day and devour everything at once.

"You know every conspiracy is made infinitely more mysterious when you put it up on a cork board," said Michael Andersen, owner and publisher of ARGNet, a site that covers alternate reality gaming in exquisite detail. "Luckily, with the way they've designed the site, you can consume it piece by piece."

Andersen has yet to play Ingress; he is still awaiting his invitation to the beta. But he said Google is following many steps associated with successful alternate reality games, starting with the way they introduced it. While Ingress launched Thursday, aspects of it have been in public view since Comic Con in San Diego in June. There, a person claiming to be an artist named Tycho stood up and shouted about mind control for a couple minutes before being carted off by security. Posters that Tycho created materialized on his Tumblr hinting that whatever came next would be global in nature and tied to a series of landmarks.

"That kind of event, where the online activities merged with real-world activities, is a really cool thing to watch," Andersen said. "You're seeing all these different threads come together and pull apart."

The Niantic Project Web site launched last week, and by the time the game arrived Thursday there was already an impressive community wiki up and running with tons of information about everything that has been discovered so far.

And the portal-capture game that now makes up most of the Ingress app experience may be only the first chapter. Hanke told All Things D that the game could run as long as a year and a half, which would be a long time to spend fortifying virtual portals.

Conspiracy theory, meet Jamba Juice

The thing about layering things onto a world that can only be seen via smartphone is that it tends to make the real world look boring by comparison. On my smartphone, I was capturing portals and linking them to far-flung places; in the real world, I was a guy standing on a corner dodging people heading back to the office after lunch. Alternate reality games promise a kind of magical intersection between real and virtual worlds; Ingress, at least at this early stage, hasn't quite delivered it.

Some popular ARGs have managed to incorporate physical clues into their gameplay -- having players pick up a ringing pay phone in the middle of the city to hear a snippet of narrative, for example, or finding clue inside a bowling alley inscribed on a bowling ball. But unless the budget for Ingress is larger than expected, it's hard to imagine Google leaving physical clues around the world.

"One of the limitations of having a global game like this, where everyone can play, is it becomes much harder to pull through those physical aspects," Andersen said.

There's also the question of how Google will integrate advertising into the game. Zipcar and Jamba Juice are among its sponsors, according to All Things D; will players be able to capture a local smoothie store for in-game bonuses? It will if nothing else be interesting to see how Google works big brands into a story about mind control.

But these are early days in Ingress. Google has laid a few cards on the table, with the promise of many more to come. And until they do I'll be watching from afar, at least until they add street names to their maps.