Escaping Google's gravity: How small search engines define success

The search world is filled with Davids flinging stones at Google's Goliath. DuckDuckGo and Blekko, two engines fighting the search giant, may stand the best chances of hitting their mark.

It's not easy to compete in the world of search. Once you get past Google's juggernaut, you're still squaring off against Yahoo and Bing. But some of the smaller search engines are looking to attract people by offering what the others can't: peace of mind.

DuckDuckGo has skyrocketed to relative prominence as a Google alternative in the wake of National Security Agency spying allegations, initiated by whistleblower Edward Snowden. The search engine, founded in 2007 by Gabriel Weinberg, pulls in its results from numerous sources, but its best weapon is its pro-privacy stance.

"If you have a choice between great results, and great results and privacy," Weinberg said, "I think some people will choose the second one."

Weinberg has built and staked DuckDuckGo's reputation on its privacy policies. The search engine says that it "does not collect or share personal information," and it does not store IP addresses or "Unique User" numbers which many sites use to identify visitors by something other than a simple user name. It also doesn't share any of the data it does collect with third-party affiliates.

So how does DuckDuckGo get by in a search engine world that has learned to mine customer data for every possible nugget of information? It gets some venture capital funding, but the majority of its revenue comes from search ads -- no different from Google.

DuckDuckGo's business, Weinberg said, could be profitable -- if the company wanted it to be. It's made a lot of hires, he said, thanks to some funding from Union Square Ventures, but it hasn't been focused on making money.

"We have a sustainable business," he said, and emphasized getting "the big guys" to change their policies on search query privacy and instant answers.

While describing DuckDuckGo as "lean" but "not in danger of needing to raise money," he also admitted that the company could be more successful. But he was reluctant to define what success would mean to DuckDuckGo. "I don't think about it much," he said.

The company's long-term goal is to show up on ComScore market share reports, which it's a long way off from doing. But DuckDuckGo's privacy-focused marketing has helped rocket the search engine to more attention than ever before in the wake of the PRISM and NSA revelations.

It's getting more than 3 million searches per day now, up by about one-third since Snowden blew the whistle on the U.S. government. Search engine observer Danny Sullivan rightly points out that DuckDuckGo's 90 million monthly searches are practically invisible compared with Google's 13.3 billion monthly searches. But the sharp jump in DuckDuckGo traffic indicates anything but search engine apathy, argued Weinberg.

"If you assume only a few people know about us, then look at our growth," Weinberg said. "We're doing quite well."

Search engine Blekko does even more global traffic than DuckDuckGo, at 5 million daily searches. Blekko Chief Technical Officer Greg Lindahl pointed to his engine's well-rounded approach to search as reasons for its success. "If you're into exploring the Web, instead of just getting a specific answer, you'll find us better," he said.

Blekko, Lindahl said, has been focused on retaining a robust, broader approach to search. Think more along the lines of the 1980s Coca-Cola formula change. Whereas "New Google" is all about tying your personal interests to your search results so your searches are contained in a filter bubble of your preferences, Blekko is more like "Google Classic."

"If you don't click on news stories on Google, they don't show you news," eventually reducing the diversity of results, Lindahl said. "It can take a long time to disabuse Google of the notion that you don't like news."

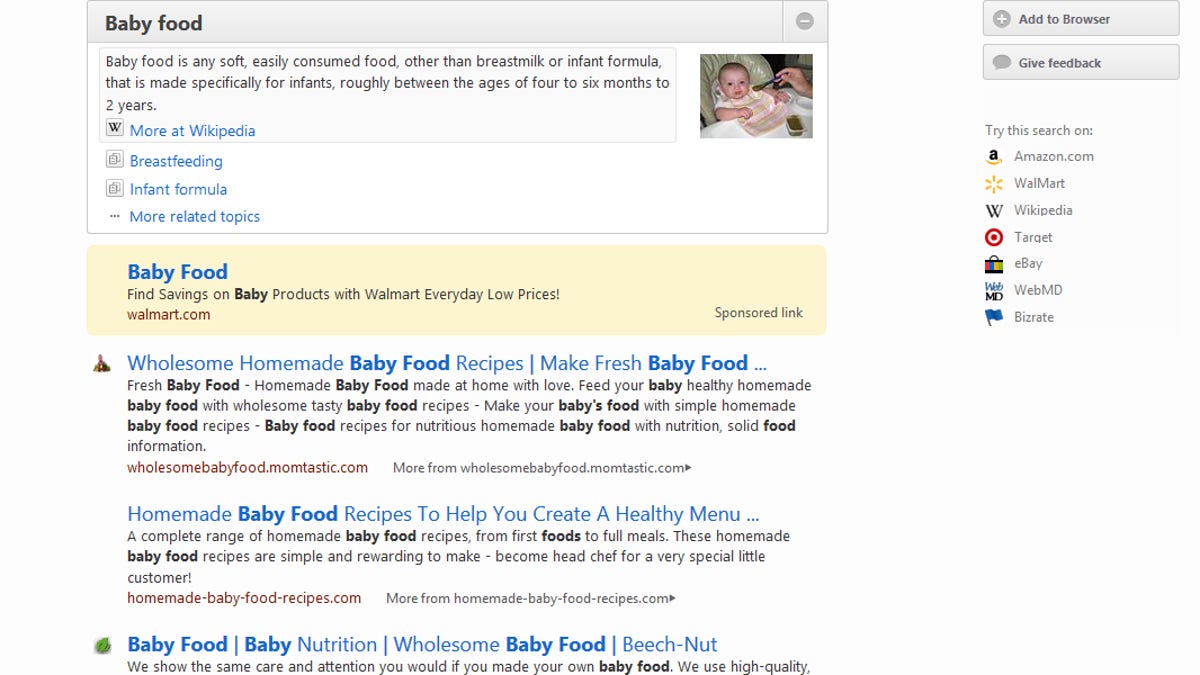

Blekko shows results relating to a wide range of possible intentions, he said. If you search for baby food, he suggested, Blekko will show categories for buying it, making it, and health concerns related to it.

Blekko shows results that make fewer assumptions of the user's intentions because it does its own indexing of the Web, Lindahl explained.

"We feel that to be successful we have to do more than show results from somebody else's index," he said. But "we don't think that we directly compete with any of the smaller options. Everybody competes with Google, and we have very friendly relations with all the alternatives."

Not unlike the alternative browser market, as the Web grows, the successful niche search engine doesn't necessarily have to peel millions of users away from the existing juggernauts. It simply has to convince enough people that privacy, or less presumptuous results, are the better way to do business.