China's great Big Tech experiment matters everywhere

Chinese authorities have spent the past year cracking down on Big Tech. Its impacts have already been felt around the globe.

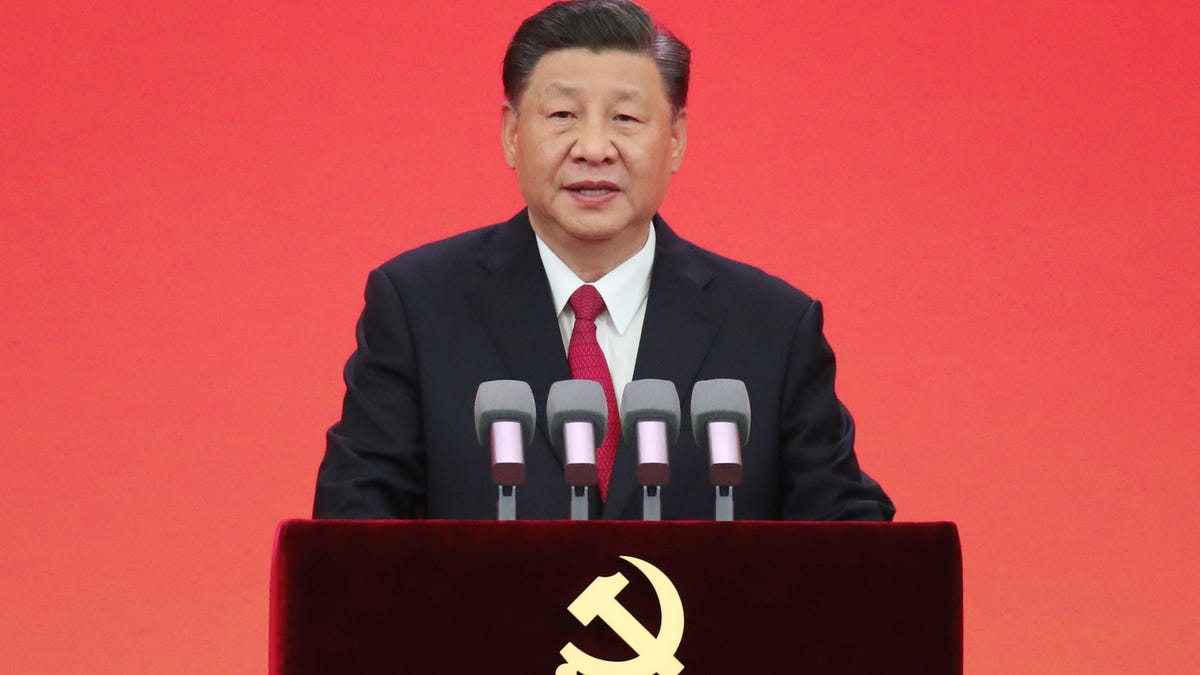

President Xi Jinping has run China for almost a decade.

As the US slowly grapples with how to handle the Googles and the Facebooks of the world, China is in the middle of a once-in-a-generation experiment in regulating Big Tech. The Chinese Communist Party has spent the last year enacting an unprecedented clamp down on its tech industry. The rest of the world should pay attention.

Authorities called off a tech IPO that would have been the biggest of all time, limited children to three hours of video games per week and signed sweeping new data privacy rules into law. The country's central bank barred the use of crypto. A year in, the Party's censorious zeal remains impactful. Yahoo and Microsoft have both pulled services out of the country over the past month, citing challenging legal and business environment, and Epic Games will shutter its Chinese Fortnite servers on Nov. 15.

The crackdown is part of a larger Chinese government campaign for "Common Prosperity," a phrase that's become ubiquitous in President Xi Jinping's speeches. Fueled by an economy that's grown prodigiously over the past 20 years, Chinese wealth inequality has gaped open. The country's top 1% holds 30% of the wealth. To bridge the gap, the party is targeting celebrity culture, debt-addicted companies like Evergrande and, perhaps most importantly, Big Tech.

The world's second-largest economy is now a real-life experiment in government clashes with Big Tech. The impact will be global. China isn't Vegas: What happens there doesn't stay there, as anyone holding cryptocurrency well knows. Many of the companies being reined in also have large footprints abroad. Tencent, for instance, owns the company that makes the popular League of Legends game.

The parallels with the US, where inequality is also a potent political topic, are obvious. President Joe Biden wants the country's richest to help fund his expensive infrastructure plan. Corporations, particularly tech giants, are common targets because they pay little in tax despite making stratospheric profits. Yet Washington has been careful about reining in its tech titans, unsure how to regulate industries that move much more quickly than the law.

The Common Prosperity push has raised questions about the party's motives and the potential costs. Some observers say the party is simply solidifying power under the guise of addressing inequality. That's a tactic Xi used in a 2012 anticorruption drive that saw hundreds of officials fired or locked up in the name of washing away social ills.

Cracking down on the tech sector comes with risks. Permanent damage to the economy and financial markets -- nearly $1.5 trillion in value has been wiped from the stock market since last October -- is a distinct possibility.

"Common Prosperity, on the surface, is a good thing," said Bhaskar Chakravorti, dean of global business at Tufts University's Fletcher School. "But there's a heavy-handed aspect to this which is troublesome."

China is trying to humble its tech titans, like Alibaba founder Jack Ma.

A historic year

A year ago, Alibaba founder Jack Ma stood in front of a crowd of business luminaries in Shanghai and criticized China's unsophisticated financial infrastructure. The country's banks, he said, had a "pawn shop mentality."

Two weeks later, Chinese regulators accused Ant Group, a fintech company spun out of Alibaba, of monopolistic practices. Ant's IPO was expected to raise $35 billion, making it the biggest offering of all time. It was blocked at the last moment.

Neither Ant Group nor China's government responded to requests for comment.

Many tech titans have since been humbled. Didi, China's equivalent of Uber, was forced off app stores after allegedly violating privacy rules. Alibaba was fined $2.8 billion for anticompetitive practice. The Chinese government acquired small stakes in TikTok maker ByteDance and the Twitter-esque Weibo. Meanwhile, many moguls have read the room and decided on early retirements, including the founder of ByteDance. Ma has kept an uncharacteristically low profile over the past year.

The Chinese approach to regulating technology comes freighted with moralism. State media called video games "spiritual opium" for children. Following cues, Douyin, the Chinese sibling of TikTok, last week introduced a five-second pause between videos with messages such as "go to bed" and "work tomorrow" for heavy users.

"Tech companies are promoting a vision of a Chinese person that does not equate with Xi Jinping and his party," said Jennifer Hsu, research fellow at the Lowy Institute think tank.

While authorities are happy to make examples of consumer tech platforms, the Party is still protective of enterprise technologies it sees as vital to geopolitical security. Huawei, which makes processors and 5G equipment, has been conspicuously unencumbered.

To be sure, not everyone is convinced China's actions aren't merited in some cases. Some companies, such as Ant Group, are monopolistic and deserve to be regulated, says James Laurenceson, an economist and director of the Australia-China Relations Institute.

"China looks at the role Big Tech has played in the US, and they're not impressed," Laurenceson said. "There is the prospect that China could make better decisions around tech than we've seen in the West."

Regulators also appear ready to let up on the sector when it gets results, as the country's top financial regulator recently indicated.

Still, the Party's moves have raised eyebrows. On Nov. 1, China's new data privacy law, known as the Personal Information Protection Law, goes into effect. It's similar to Europe's GDPR, except its rules about data collection apply only to private firms, not government entities. The absence strikes many critics as a deliberate extension of government oversight that has already created a real-world surveillance state.

Frances Haugen testified about Facebook's internal documents to the US Senate on Oct. 5.

Uncommon prosperity

On Oct. 5, Facebook whistleblower Frances Haugen urged a US Senate commerce subcommittee to regulate the social network more heavily. Warning that Facebook prioritized engagement over the wellbeing of users, Haugen told legislators that the company won't change on its own.

Calls to regulate Big Tech companies have been nonstop since the Cambridge Analytica scandal of 2018. Congress wants to make Facebook responsible for content posted on its platform, while the Department of Justice has sued Google for monopolistic practices. In 2019 Facebook was hit with a record $5 billion fine for violating data privacy rules. Big Tech companies say they're open to regulation but often prove resistant to proposed changes.

China has been far more aggressive in its approach. As the US had dithered in corralling its titans, China is doing something. China, not the US, is breaking new ground.

Chakrovorti said that China's crackdown thus far offers some lessons for governments abroad, but many are on what not to do. Calling off IPOs at the last moment is something the US and EU are unlikely to mimic. Still, Chakrovorti expects the EU will look closely at the way China has levied fines on its tech giants, and says lawmakers in some US states will likely learn from China's Personal Information Protection Law.

"The whole notion of data governance and privacy protection is still a gray area," Chakrovorti said. "Everyone is looking for a model."