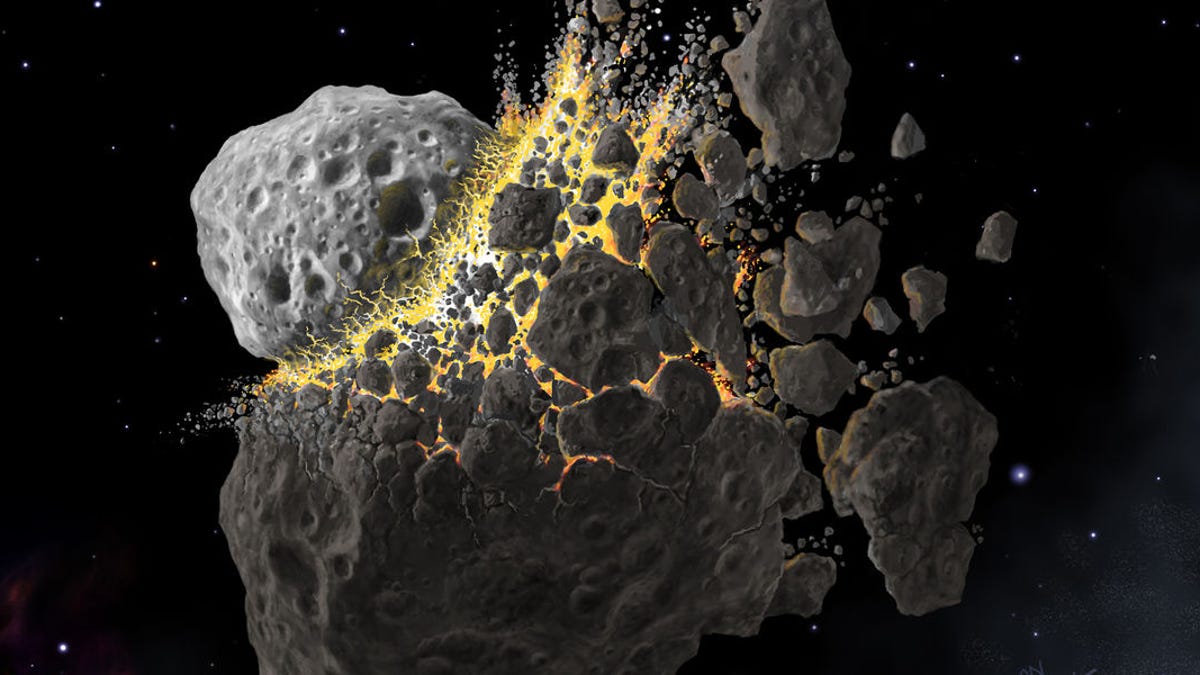

We are living in the debris field of an ancient asteroid collision

An epic crack-up in space almost a half billion years ago remains a major source of the meteorites that smash into our planet today.

Long, long ago when trilobites were one of the dominant forms of life on Earth and dinosaurs were yet to appear on the scene, there was a huge collision in outer space that broke up an asteroid, showering our planet with meteorites. Some scientists have suggested this ancient pummeling could have contributed to an explosion of biodiversity at the time, and new research suggests we've been getting hit by remnants of the cosmic crash ever since.

A study published Monday in Nature Astronomy compares the types of meteorites found on Earth before and after the collision 466 million years ago and reveals a profound difference. It shows that the prehistoric smashup still dictates our meteor "weather" on Earth today.

"Looking at the kinds of meteorites that have fallen to Earth in the last hundred million years doesn't give you a full picture," explains co-author Philipp Heck of the Field Museum in Chicago, in a release. "It would be like looking outside on a snowy winter day and concluding that every day is snowy, even though it's not snowy in the summer."

Heck and his colleagues analyzed crystals from ancient meteorites that fell to Earth before the collision and found their chemical makeup to be very different from the meteorites that have been sent our way after that dividing line 466 million years ago. Over a third of pre-collision meteorites are what's called primitive achondrites, whereas today less than half a percent of meteorites are of that type.

In other words, the meteorites that are common today are actually pretty rare on cosmic and geological time scales. Conversely, meteorites that have become rare today were more common before the collision.

It's as if we are still living under the fallout of that ancient incident, masking what would otherwise be normal meteor traffic, probably originating from the asteroid belt. In fact, Heck's team found that a significant amount of meteorites that impacted earth before the collision can be traced to Vesta, a minor planet that is one of the largest objects in the asteroid belt. It's probably not a coincidence that Vesta's history includes its own major collision event about a billion years ago.

The new research shows that ancient history isn't always just that, sometimes it also explains what's going on now.

Learning more about the history of the different kind of meteorites that space has flung our way could also help us better understand how all kinds of bodies in our solar system interact and maybe even provide humanity with a heads up prior to major collisions like the one that probably caused the legendary Tunguska Event.

Crowd Control: A crowdsourced science fiction novel written by CNET readers.

Tech Enabled: CNET chronicles tech's role in providing new kinds of accessibility.