WannaCry, what a wimp? Why security pros are staying chill

At a cybersecurity forum in London, experts call the ransomware, scary as it was at first, overexposed, unsophisticated and ultimately "a failure."

Hospitals across the UK were among the first to be hit by the ransomware.

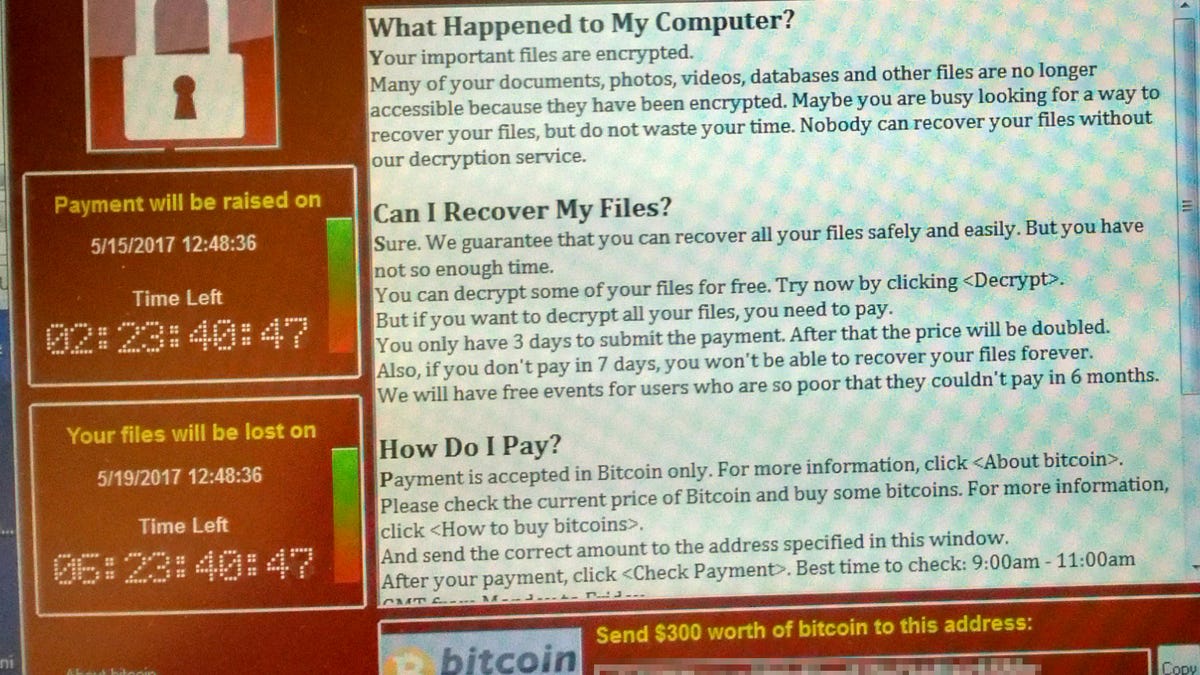

The WannaCry ransomware exploded onto the internet two weeks ago, causing havoc on Windows machines across the globe.

The initial spread has been stopped and PCs have been patched, but it was a rough stretch for the hospitals, small businesses and others that got shut down. Hundreds of people are out the $300 or $600 ransom payments.

And the threat continues to evolve.

You might expect the security industry, which was on the front lines against the attack that locked up 300,000 computers in 150 countries, to be freaking the heck out right now. But here's the weird thing: They're mostly not.

WannaCry was the first word on the tip of everyone's tongues at the Wall Street Journal's Cybersecurity Forum in London on Thursday, but the conversation surrounding the ransomware was calm and optimistic.

"Wannacry became too big," said Mikko Hypponen, chief research officer at cybersecurity company F-Secure. "It was unsuccessful. It was a failure."

As a financial attack, WannaCry went well wide of the bull's-eye. Unlike targeted ransomware attacks that tend to stay under the radar, it earned very little money -- tens of thousands of dollars rather than millions.

"Even the attackers were not aware of the potency of the weapon they were using," said Juan Andrés Guerrero-Saade, senior security researcher at Kaspersky. "It spread indiscriminately."

After examining the code, experts believe that WannaCry escaped into the wild before it was ready. "We got very lucky," said Guerrero-Saade. "It wasn't as bad as it should have been or could have been if everything had worked as was intended."

A victim's response

Do those who were victims of the attack agree? Dan Taylor is head of security for the UK's National Health Service, which was one of the first and largest victims of the attacks.

"Actually it wasn't the worst thing that could have happened to us," he told the forum's audience.

Yes, he conceded, there were service issues, but WannaCry has had no long-term effects on the NHS' systems. "It was a bit scary, but the lessons we have learned from it will make us better in the future."

When WannaCry hit, Taylor advised the NHS Trusts, which are all run as separate businesses, not to pay up, but couldn't make it a mandate. Unlike many other organizations affected by the ransomware, the NHS is about people -- who are often in emergency situations -- rather than data. "You're dealing with patients who need to use clinical services," he said. "We wouldn't say 'Don't pay.' You may have no option."

The perpetrators remain penniless

Ultimately, only 322 victims paid the ransom -- none of the NHS Trusts were among them. "That's nothing," said Hypponen.

The ransom that's been collected went to three bitcoin wallets, which ultimately makes it very difficult for the attackers to collect their spoils. Bitcoin transactions, though anonymous, are trackable, and every transaction can be seen. "Everyone is watching those wallets," said Guerrero-Saade. ""Nothing has been moved."

Ian Levy, technical director of the UK's recently established National Cyber Security Centre, encouraged people to not blow WannaCry's impact out of proportion. "It was a piece of software that was written to do something nasty," he said. "It was not a particularly sophisticated piece of software."

Cyberattacks are often referred to as "advanced persistent threats" or "ADPs," which, Levy said, make them sound much scarier and more sinister than they actually are. "Looking at the attacks over the last few years, ADP doesn't stand for 'advanced persistent threats,' it stands for 'adequate pernicious toe-rags'," he said.

Levy encouraged people not to talk about "cyberweapons" in the same breath as actual weapons -- it makes people think they have no chance of protecting themselves, when actually they do.

"People are saying WannaCry is the worst thing to hit the UK in a long time. Nonsense. Look what happened on Monday," said Levy, referring to the Manchester terror attack in which 22 people were killed. "Let's keep things in perspective."

Logging Out: Welcome to the crossroads of online life and the afterlife.

Tech Enabled: CNET chronicles tech's role in providing new kinds of accessibility.