Search Earth with AI eyes via powerful satellite image tool

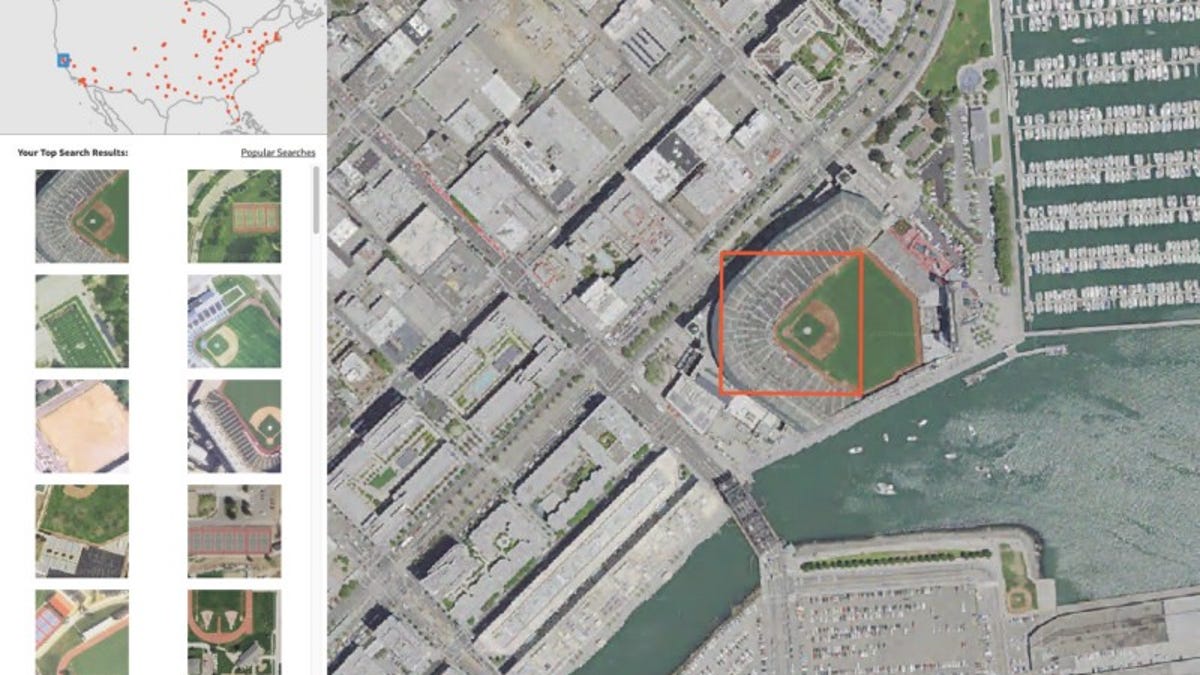

GeoVisual Search makes it possible to search satellite images of the entire world for matching objects. And it's just the beginning.

Want to know where all the wind and solar power supplies in the US are for some brilliant renewable-energy project? Or plot a round-the-world trip hitting every major soccer stadium along the way? It should be possible with a new tool that lets anyone scan the globe through AI "eyes" to instantly find satellite images of matching objects.

Descartes Labs, a New Mexico startup that provides AI-driven analysis of satellite images to governments, academics and industry, on Tuesday released a public demo of its GeoVisual Search, a new type of search engine that combines satellite images of Earth with machine learning on a massive scale.

The idea behind GeoVisual is pretty simple. Pick an object anywhere on Earth that can be seen from space, and the system returns a list of similar-looking objects and their locations on the planet. It's cool to play with, which you can do at the Descartes site here. A short search for wind turbines had me dreaming of a family road trip where every pit stop was sure to include kite-flying for the kids.

Perhaps this sounds just like Google Earth to you, but keep in mind that tool just allows you to find countless geotagged locations around the world. GeoVisual Search actually compares all the pixels making up huge photos of the world to find matching objects as best it can, an ability that hasn't been available to the public before on a global scale.

Fun as it is, the tool also gives the public a taste of Descartes' broader work, which so far has focused largely on agricultural datasets that can do things like analyze crop yields.

"The goal of this launch is to show people what's possible with machine learning. Our aim is to use this data to model complex planetary systems, and this is just the first step," CEO and co-founder Mark Johnson said via email. "We want businesses to think about how new kinds of data will help to improve their work. And I'd like everyone to think about how we can improve our life on this planet if we better understood it."

The tool's not perfect. I tried searching for objects that look similar to a large coal mine and power plant here in northern New Mexico and ended up with a list of mostly similar-looking lakes and bridges. Searching for locations similar to the launch pads at Cape Canaveral returned an odd assortment of landscapes that seemed to have nothing in common besides a passing resemblance to concrete surfaces.

The algorithm can easily mistake a whole lot of coal for a whole lots of water.

"Though this is a demo, GeoVisual Search operates on top of an intelligent machine-learning platform that can be trained and will improve over time," Johnson said. "We've never taught the computer what a wind turbine is, it just determines what's unique about that image (i.e., the fact there is a wind turbine there) and automatically recognizes visually similar scenes."

Right now the demo relies on three different imagery sources that include more than 4 petabytes of data altogether. You can search in the most detail using the National Agriculture Imagery Program (NAIP) data for the lower 48 United States because it has the highest resolution of one meter per pixel, making it possible to spot orchards, solar farms and turbines, among other objects.

Four-meter imagery is available for China that makes it possible to recognize slightly larger things like stadiums. For the rest of the world, Descartes uses 15-meter resolution images from Landsat 8 that are more coarse but still allow for identification of larger-scale objects like pivot irrigation and suburbs.

"As a next step, we certainly want to start to understand specific objects and count them accurately through time," Johnson said. "At that point, we'll have turned satellite imagery into a searchable database, which opens up a whole new interface for dealing with planetary data."

Descartes was spun out of Los Alamos National Lab (LANL) and co-founded by Steven Brumby, who spent over a decade working in information sciences for the lab. Near the start of his time at LANL, a massive wildfire nearly destroyed the lab and Brumby's home. More importantly, it sparked Brumby's interest in developing machine-learning tools to map the world's fires.

"At that time when we did the analysis (of satellite images of the fire's aftermath) it was pretty clear the fire had been catastrophic, but there was a lot of fuel left," Brumby told me when I visited Descartes' offices in Los Alamos last year.

When some of that remaining fuel burned in another big Los Alamos wildfire in 2011, Brumby says he was able to help out. During his time at LANL he was often called on for imagery analysis when disaster struck, from 9/11 to Hurricane Katrina and the breakup of the Space Shuttle Columbia. All those years of insight led to another Descartes project to analyze satellite imagery to better understand and perhaps even predict wildfires around the globe.

"You can use satellite imagery to warn you of stuff that's coming down the road and if you listen to it, you can be prepared for it," Brumby said.

Before and after the 2000 Cerro Grande fire, with the burn scar shown in bright red.

Brumby and Johnson spent the better part of an afternoon laying out the short- and long-term vision for Descartes Labs when I visited. In the short term, the company has been working in agriculture to better monitor crops, feed lots and other data sources.

"One of the things we're building with our current system is a continuously updating living map of the world, which is the platform I wish we had when we had to deal with some of these disasters back in the day," Brumby said.

Being able to check in on any part of the world in real time is one thing, but Descartes hopes to go further by applying artificial intelligence to see things in all those images that might not be immediately obvious to our eyes: the patterns that tie together all the activities captured in those countless pixels.

If a picture really is worth a thousand words, tools like the ones Descartes is developing could help write volumes about what our satellites are really seeing.

Solving for XX: The industry seeks to overcome outdated ideas about "women in tech."

Crowd Control: A crowdsourced science fiction novel written by CNET readers.