Why you shouldn't panic about coronavirus 'doomsday variant' headlines

Commentary: A variant alleged to be "worse than delta" has received a lot of media attention, but experts say it's far too early to be concerned.

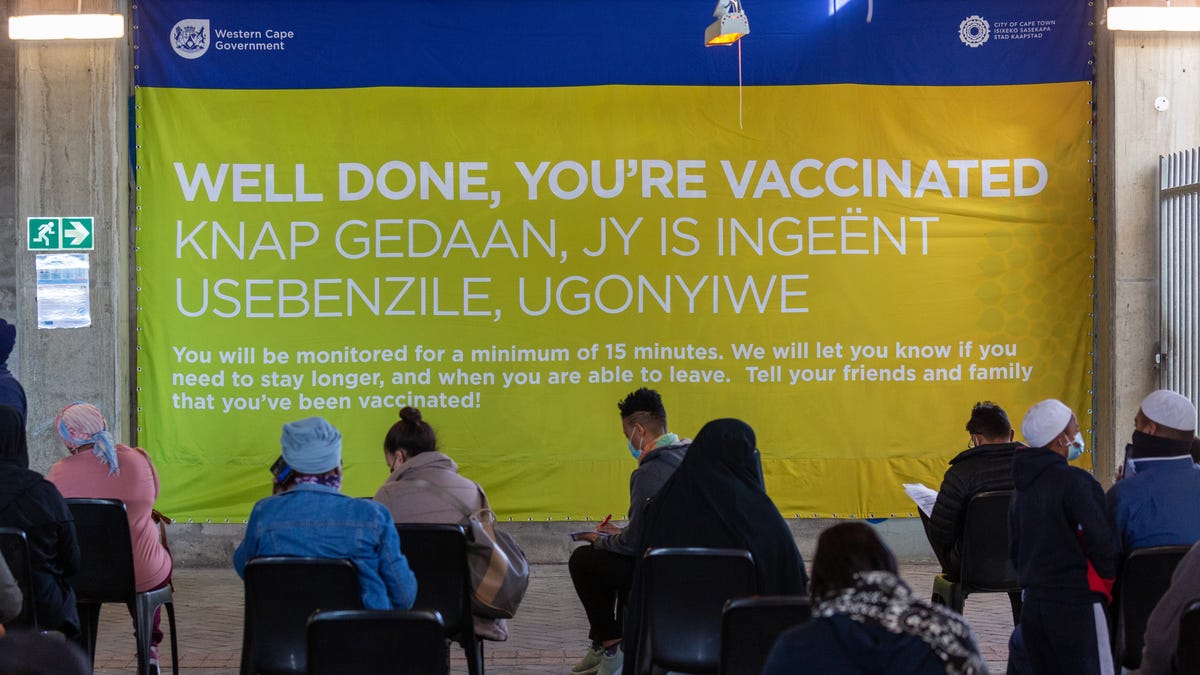

Vaccination is the best way to protect yourself from the coronavirus, including variants like delta.

The delta variant of coronavirus has forced a rapid rethink on the pandemic endgame. Its rapid transmission has seen it run rampant in places with low vaccination rates, like Australia, forcing half a nation into extended lockdown. In places with good vaccine coverage, like the UK, Iceland and Israel, delta has triggered a surge in daily case numbers.

Fortunately, though delta is more transmissible than previous variants, vaccines still protect us from its worst effects. In the face of rising cases, the jabs have been able to stem the flow of hospitalizations and death. But the emergence of delta has concerned scientists, experts and the public alike -- it has inspired a feeling of powerlessness and uncertainty about just how long the pandemic will be with us.

So when I saw headlines about a so-called "doomsday variant" of the coronavirus earlier this week, I felt deflated. They shouted that this new variant was "worse than delta." They warned of concerning mutations. But the stories left out valuable context.

In short, there's no reason to panic. There's no doomsday variant (we don't name variants this way), and there's little evidence this new mutant strain is worse than delta. "There is no evidence it is particularly transmissible, and it has not been flagged as a variant under interest so far," says Francois Balloux, a computational biologist at University College London.

The strain, currently dubbed C.1.2, was first detected in South Africa in May and in the last week has gathered significant attention because of a preprint study by South African researchers published Aug. 24. Preprints are research articles that haven't yet undergone a peer review process.

The preprint didn't gather much momentum until a Twitter thread by a former Harvard epidemiologist went viral on Aug. 29, rippling out across the Twitterverse. Hours later, mainstream publications across the world had cobbled together stories with alarming headlines foreshadowing disaster.

But the doomsday calls are premature and dangerous. They highlight a concerning pattern of reporting that has existed since the earliest days of the pandemic.

The C.1.2 coronavirus strain

First, the good news.

Coronavirus variants are constantly being produced in the bodies of infected individuals due to mutations in the genetic code. Most of these mutations are not beneficial and do not get passed on to the next generation of virus particles. This is expected.

Occasionally, however, a mutation in the genetic code of the coronavirus gives it a survival advantage. It becomes the dominant form of the virus in one person and, if they pass it on, goes on to infect many others. This is what happened with delta, somewhere in India, earlier this year.

Delta's constellation of mutations allowed it to evade the immune system a little better and move from person to person much faster. Good for a virus, bad for us.

Scientists are constantly monitoring new strains of SARS-CoV-2 that emerge across the globe. The World Health Organization classifies emerging strains that may pose a problem as "variants of interest" or "variants of concern." Delta, for instance, is a variant of concern and still accounts for around 90% of South African cases.

The South African research team is trying to evaluate whether C.1.2 would fall into one of these categories. Like many other researchers across the world, they've been monitoring new cases of COVID-19, analyzing the genetic code of each virus that infects patients and trying to find any patterns or unusual mutants.

This monitoring is crucial to detect changes in new strains. When it comes to C.1.2, the preprint study explains that there are some mutations that could give rise to a problematic variant. But it's very, very early days for research into this strain, and no functional studies have been performed in the lab to show C.1.2 might evade immunity or vaccines.

It makes sense to publish these preliminary results because the strain is notable for its unusually high mutation rate and does contain a variety of changes to its genetic code that have been detected in previous variants, including alpha, beta and gamma. However, alone, these changes aren't enough to say it's "worse than delta." It's important to note that, as more studies are performed, this may change, but it's far too early to say.

"It is too early to determine whether or not it is likely to create major problems or indeed even take over from the delta variant," said Adrian Esterman, an epidemiologist at the University of South Australia.

The science of understanding the significance of a new variant is slow -- much slower than an endlessly updating Twitter feed. The team will continue to track the emergence of C.1.2, but this is a slow, considered process involving a lot of lab work.

And that is where the problem lies.

Science and social media don't always mix well.

Persistent preprint problems

Getting scientific studies out as quickly as possible during the pandemic has been incredibly beneficial. Being able to quickly share new results and collaborate with other scientists across the world can advance understanding of the virus at a pace that matches how quickly it spreads. Geneticists, like Balloux, are able to monitor new lineages of the virus because of how quickly they spread.

And preprints are critical here, too -- they allow research to be shared almost instantaneously without having to go through peer review, which can take weeks to months.

Scientists can upload their manuscripts to websites online and have their results instantly scrutinized by their peers. Sometimes, other scientists will find flaws in the work and come to different conclusions. This is the scientific process in action. One study inspires the next or a new way of thinking until a truth is uncovered.

But science is incremental. It's a step-by-step process that takes a lot of time and is usually performed behind the curtain. The public then only really gets to see the end result: a new drug, a vaccine, a brain implant, a discovery decades in the making, a world-changing find agonized over for years.

During the pandemic, those incremental steps have been made visible to the public. This creates a problem. The slow pace of science does not match up with the extreme speed of information.

As early as Feb. 5, 2020, when scientists were only beginning to understand the coronavirus, they were confronted by this fact. Preprint papers were quickly making their way to the public via social media platforms and news reports. Often accompanied by alarming language and caps-locked cries, posts and news stories quickly went viral.

In the information vacuum of the early pandemic, fear and panic reigned supreme.

But the problem hasn't really gone away in the year and a half since. C.1.2 is just the latest example of the struggle between science and social media and how reporters deal with preliminary studies.

In Twitter posts and early reports, some of the crucial context around C.1.2 was missing. For instance, in a piece for the Conversation, the South African research team behind the preprint wrote that vaccines will still offer high levels of protection against C.1.2. This is an important note and knocks the "worse than delta" assertions on their head. Getting vaccinated remains key to battling any emerging variant of the coronavirus.

The team also clarify they are collecting more data to understand the transmissibility of C.1.2. They're acting cautiously -- but tweets and reports often do not.

Misinformation continues to be a problem during the pandemic, but one of the key battlegrounds remains the social media platforms where alarmism and doom-saying thrives. No one is immune to misinformation or scary headlines. Some positive strides have been made. Twitter, for instance, now allows reporting of political or health misinformation, and YouTube has been proactive in removing inaccurate content around therapeutics.

But in the 21 months since the pandemic began, the same problems persist. Bad studies go viral. Alarmist headlines get clicks. And if C.1.2 doesn't turn out to be the doomsday variant it has been incorrectly touted as, real damage is done. It can seem like the experts backflipped or didn't know what they were talking about. Trust in scientists and science communicators is eroded.

So keep in mind, there is uncertainty in science and research. Scientific progress does not occur on the timescales we're used to seeing on our Twitter feeds. The pandemic is an ever-changing threat. New variants will emerge and so will new questions. Answering them takes time, despite what the headlines might have you think. Stick to trusted sources of information, like the WHO and your local health networks, and read publications with a track record of honest, fact-checked reporting.

On top of all that, perhaps the best advice I can give is to just log off Twitter and get a vaccine.