My past life as a projectionist: How robots took my job

Commentary: I’m 25 and already my job has been stolen by machines.

Robots might enslave and kill us one day, but more importantly, they're going to take our jobs.

If it makes you feel better, machines have been slowly replacing us for centuries. In the 19th century they became textile workers, in the 1950s they became assembly-line workers and in 2003 an unkillable robot from the future even became governor of California. No wonder people are scared.

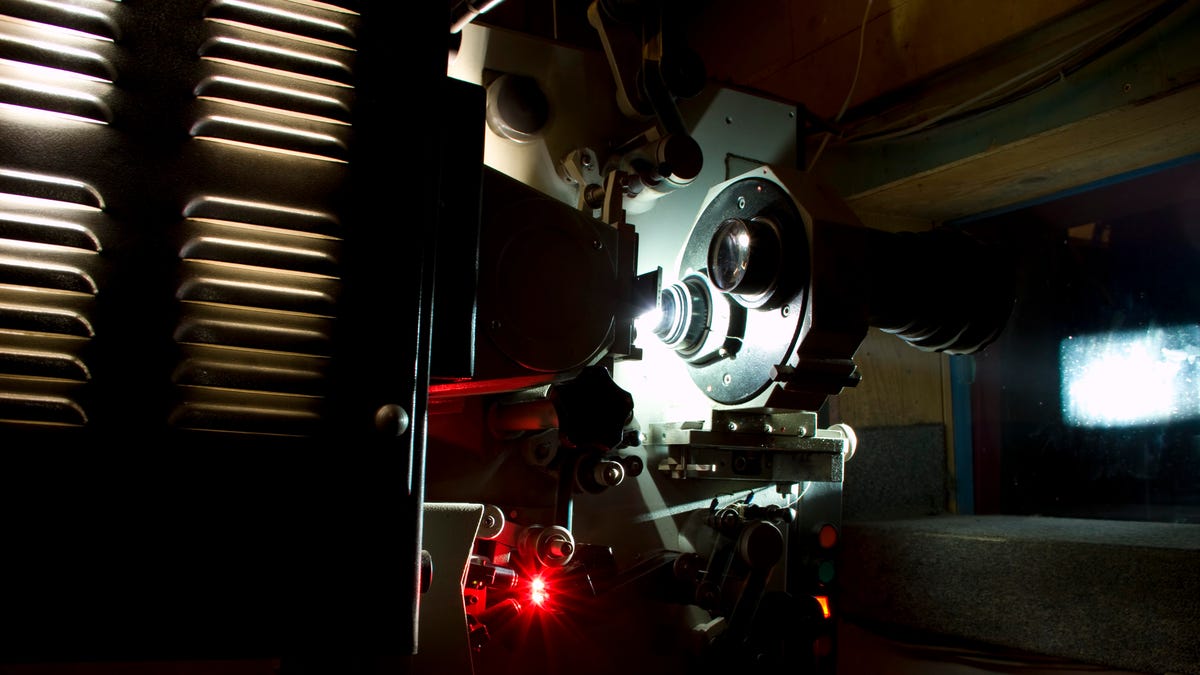

I myself have been a victim of industrialisation. Kind of. Between 2011 and 2014, when I was studying at university, I was a cinema projectionist on the side. It was wild.

It took two months for the grizzled projection vets to train me to lace up 35mm film on a projector -- I remember one of the first lace-ups I got right off the bat was for Bridesmaids. But on my very first solo shift everything changed. Head office made the decision to phase out 35mm projectors for entirely digital ones. After learning the arcane trade of projection, it was deflating: Everything I knew would be useless six weeks later.

Invariably, the first question people ask me is the same. "Did you just sit in the projection room and watch movies?" No. I'm offended at the implied accusation of negligence.

I sat in the projection room and finished uni assignments. It's way different.

Yeah, pretty much.

But seriously, there was no time for this in the 35-mm era. If you weren't darting around the room to lace up projectors, you were splicing trailers onto prints, maintaining equipment or physically moving prints around or between rooms.

(And even if there was time, the projection rooms were soundproof, which means no sound comes in. You'd have to watch with audio from a tinny speaker about as good as the one on your phone.)

More important than any of those duties, though, was precision. The consequences of error were huge. For instance, if a print wasn't secured properly on its platter it could spin off the edge and wreck shop. This ends up with you having to stop the movie midway through and spend four to six hours untangling an ungodly amount of film.

Naturally, this would mostly happen during the 9:30 p.m. session, meaning you wouldn't leave until 4 or 5 in the morning. Thankfully, I wasn't around in the 35mm print days long enough for this to happen to me.

Especially concerning were Bollywood prints. They'd arrive a few hours before first screening as opposed to the standard three days, and almost always in something resembling a damp hemp box. Bollywood prints were notoriously flimsy and prone to going rogue on the platter.

It sounds odd to say, but there was an art to lacing up a projector. It always tickled me. You could tell who was working on a given night based on the way the projectors were laced up. Each person had a preferred route. Some had tricks and shortcuts they learned over a period of decades. But it was a dying art.

All the full-time projectionists were gone about six months after I started. Some quit, others were made redundant. I stuck around, because I was a casual and I was cheap.

"Get your degree and run for the hills," I remember my old boss telling me. I was going to do that anyway.

The problem was simple: Computers are extremely good at being projectionists. It's tempting to get nostalgic about the age of the human projectionist, to wax lyrical about the benefit of a human touch, but there's no competition.

Robots were so good at being projectionists that it was a struggle to find work to do. Once a week I'd make playlists, little more complicated than doing so in Spotify, for the projectors to run: This ad here, that trailer there and then the feature film here. Then it was scheduled, and the computers would do the rest. No lacing up, no splicing trailers to films, no moving prints around.

Instead, I'd wander the hallways looking for lights to fix, or I'd clean the port glasses that projectors shoot through. Stuff that needed to be done once a fortnight got done once every couple of days.

Once digital kicked in, you could get away with more movie watching. Remember the New York battle scene in the first Avengers flick? The one that starts with the famous "That's my secret, I'm always angry" line? I watched that about 130 times. This was in the digital era, and Avengers was in cinemas forever. I stopped to watch every time I walked past a projector playing that scene. Good times.

When I started, back in 2011, there were often four people working each day. Two projectionists doing the day shift, and two doing the night. That got cut down to one a day, one a night. Then half your shift was being a projectionist, the other half cleaning cinemas or whatever.

Last I checked, my cinema chain now has one projectionist for every two sites. They drift in between, making sure everything is in order, but computers do most of the work.

Some really intelligent people are really scared of AI. Philosopher, neuroscientist and general smart guy Sam Harris has a terrifying TED Talk on artificial intelligence, while Elon Musk, who is essentially Iron Man, calls it the "biggest risk we face as a civilisation." The public are onto AI as well. Around 73 percent of US citizens think AI will kill more jobs than it makes, according to a Gallup Poll.

AI can be scary because of the complexity of the jobs it can replace. I was 21 the first time a machine took my job, and I'm going to bet it's not the last time. Then again, when you hear about, say, Paris' last porn cinema being forced to close because of the advent of internet porn, it's clear that some jobs are better left to the robots.

Blockchain Decoded: CNET looks at the tech powering bitcoin -- and soon, too, a myriad of services that will change your life.

Follow the Money: This is how digital cash is changing the way we save, shop and work.