This is why DOJ accused Apple of fixing e-book prices

What's the difference between selling books for wholesale and selling through the agency model? Here's what Apple and some publishers are accused of.

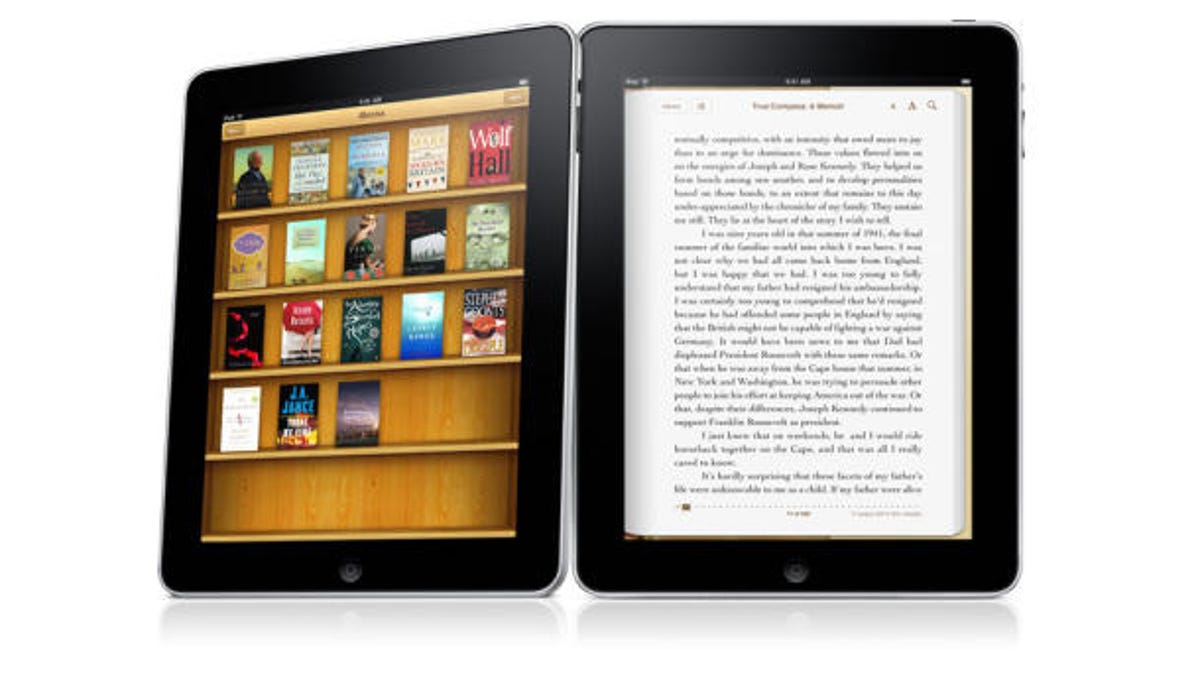

In 2010, Apple enabled some of the top book publishers to set their own prices for electronic books they made available on the iPad.

Since then, prices that consumers pay for e-books have risen and Amazon and other online book sellers that discount have been under pressure. The government said today in an antitrust complaint filed in New York, that the arrangement Apple struck with publishers Hachette, HarperCollins, Macmillan, Penguin, and Simon & Schuster was an attempt to control prices and violated the law.

The case could hurt Apple's position in the e-book market, a sector that is growing in popularity, should the publishers be forced to move away from a pricing model that benefited Apple. If it is proved that Apple is guilty of anti-competitive practices, the goodwill the company has generated among consumers over 30 years could also be damaged.

Here's what we know about why the government is peeved.

Perhaps Steve Jobs best explained the deal Apple offered publishers in his biography, which was written by Walter Isaacson:

"We told the publishers, 'We'll go to the agency model, where you set the price, and we get our 30 percent," Jobs told Isaacson. "And yes, the customer pays a little more, but that's what you want anyway."

Jobs then told Isaacson that the publishers were able to force the agency model on all the other retailers. That's what some say is a smoking gun.

Apple and the publishers have denied colluding on price. But the government alleges that top managers for the publishing companies were in regular contact to make "assurances of solidarity." Some of the publishers have now agreed to settle with the DOJ while talks with other companies continue, according to the Wall Street Journal. Apple has refused to participate in the settlement talks, according to reports.

An agency model allows the publisher, not the retailer, to set prices.

A wholesale model allows retailers to negotiate with publishers for rights to electronic books and then sell them to consumers for whatever price they want. This model is believed to be the one that fosters the most competition between retailers and most beneficial for consumers.

While Jobs' comments alone seem like trouble enough, add this to the mix: Apple had most-favored-nation status with some of the major publishers, according to reports. This means Apple was guaranteed to receive the lowest prices publishers offered to competitors. In other words, Apple would never pay more for books than its rivals.

Deals like this aren't new but seldom are they heaped onto arrangements like the one Apple proposed in 2010. In combination, it raises questions about whether someone is trying to stifle competition. Here's a good spot to remind you about the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890.

The main thrust of the act is pretty simple: "To protect consumers by preventing arrangements designed, or which tend, to advance the cost of goods to the consumer."

The law wasn't intended to thwart competition or prevent a skillful competitor, one who found a way to attract more business through legitimate means, from thriving. But deciding what is or isn't legitimate competition can be tricky.

Book publishers argue that in 2010, before Apple approached them with the agency model plan, Amazon was running away with the market. The company's Kindle e-reader was a hit. Amazon was slashing prices so much that the publishers feared that Barnes & Noble and other sellers would get priced out, leaving them and consumers with one massive player dominating book sales.

Media companies, including record companies and movie studios, are happiest when a retail market teems with distributors. This enables them to play one off the other.

The move to an agency model will lead to more diversity among sellers, according to Maja Thomas, a senior vice president of digital at Hachette. Speaking on a panel at the On Copyright conference two weeks ago, Thomas said the company's move to an agency model would help stimulate competition among retailers, nurture a healthier market and lead to more price flexibility.

Thomas told the audience that without a move to the agency model, indie bookstores would find it difficult to compete. She also asked how the agency model was any different from the arrangement Hollywood film studios have with theater owners.

"You could say film companies collude to force viewers to see first-run movies in theaters," Thomas said.

Thomas brings up a good point. I'm still trying to find out why the movies available for sale and rental on Amazon, iTunes, and Vudu are all roughly the same price.