Venus is hell, but science is seriously looking for life in its skies

Researchers float a hypothesis about how microbial life could actually survive in the clouds above the toxic and overheated planet.

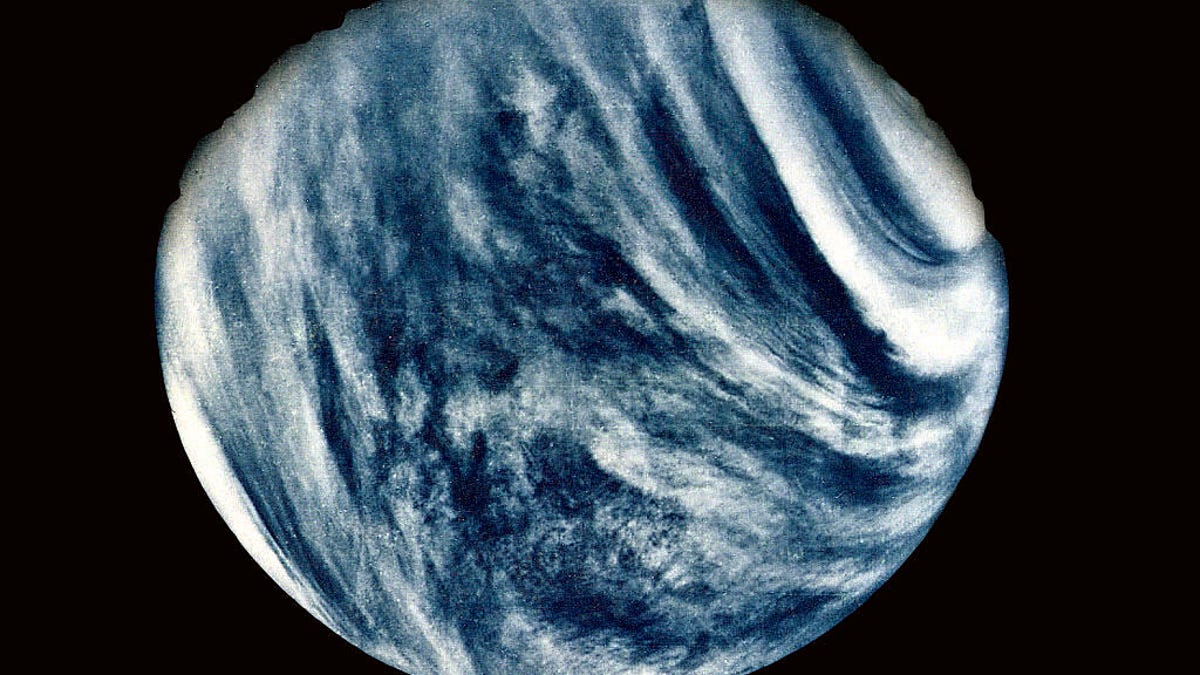

An ultraviolet image of Venus captured by Mariner 10.

For decades, the verdict has been in on Venus: It's a toxic, overheated, crushing hellscape where nothing can survive. But increasingly, our planetary next-door neighbor is getting a second look, or at least its clouds are.

Recent research proposes a way that microbial life could actually survive for eons aloft in Venusian vapors. If such a hypothesis were ever proved true, it could prompt a reevaluation of how and where we look for life in the universe.

Though the surface of Venus is subject to punishing pressures, and to temperatures around 800 degrees Fahrenheit (426 Celsius), certain layers of its atmosphere are quite nice. NASA has even gone so far as to propose creating a sort of cloud city at the second planet by sending craft that could hover at an altitude of around 30 miles (50 kilometers), where conditions are actually similar to those on Earth's surface.

Some measures suggest that aside from Earth, the atmosphere of Venus is the most habitable place in our solar system, because the pressure and temperature are in the range we're used to. Still, there'd be no breathable air -- and then there's the problem of sulfuric acid in the atmosphere eating away at your respiratory system and other vitals.

Of course, no one's expecting there to be any large humanoids flying around above the clouds of Venus. But there is this question: Could some nearly invisible microbes be persistently floating around, eking out one of the more precarious lifestyles imaginable, on the edge of one of the most malignant worlds known? Hardy organisms like tardigrades can survive radiation, extreme temperatures, starvation, dehydration and even the vacuum of space. Perhaps they have cousins on Venus?

Carl Sagan speculated about life in the clouds of Venus back in 1967, and just a few years ago, researchers suggested that strange, anomalous patterns seen when looking at the planet in ultraviolet could be explained by something like an algae or a bacteria in the atmosphere.

More recently, research published last month in the journal Astrobiology, from leading astronomer Sara Seager at MIT, offers up a vision of what the life cycle above Venus might be like. Seager has been a 21st century leader in the search for exoplanets, biosignatures, and worlds similar to our own. She's currently the deputy science director for NASA's Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite mission (aka TESS).

Seager and her colleagues suggest that the most likely way for microbes to survive above Venus is inside liquid droplets. But such droplets don't stay still, as anyone who's ever seen rain knows. Eventually they grow large enough that gravity takes over. In the case of Venus, this would mean droplets harboring tiny life forms and falling toward the hotter, lower layers of the planet's atmosphere, where they'd inevitably dry up.

"We propose for the first time that the only way life can survive indefinitely is with a life cycle that involves microbial life drying out as liquid droplets evaporate during settling, with the small desiccated 'spores' halting at, and partially populating, the Venus atmosphere stagnant lower haze layer," the paper's summary reads.

These dried-out spores would go into a sort of hibernation phase similar to what tardigrades can do, and eventually be lifted higher into the atmosphere and rehydrated, continuing the life cycle.

This is all speculation. Fortunately for Venusian life hunters, a number of astronomers and their instruments are trained on the complex planet. NASA is even considering a mission, dubbed Veritas, that could depart as soon as 2026 to orbit and study Venus and its clouds.

Meanwhile, more data from Venus, and perhaps new discoveries, may soon be incoming. The forecast for the planet remains, as it has for some time, cloudy with a chance of microbes.