The trail of hidden lakes on Mars finally goes dry in new study

A Martian Great Salt Lake was once thought to be hidden beneath a polar ice cap. Turns out it may have been a mirage.

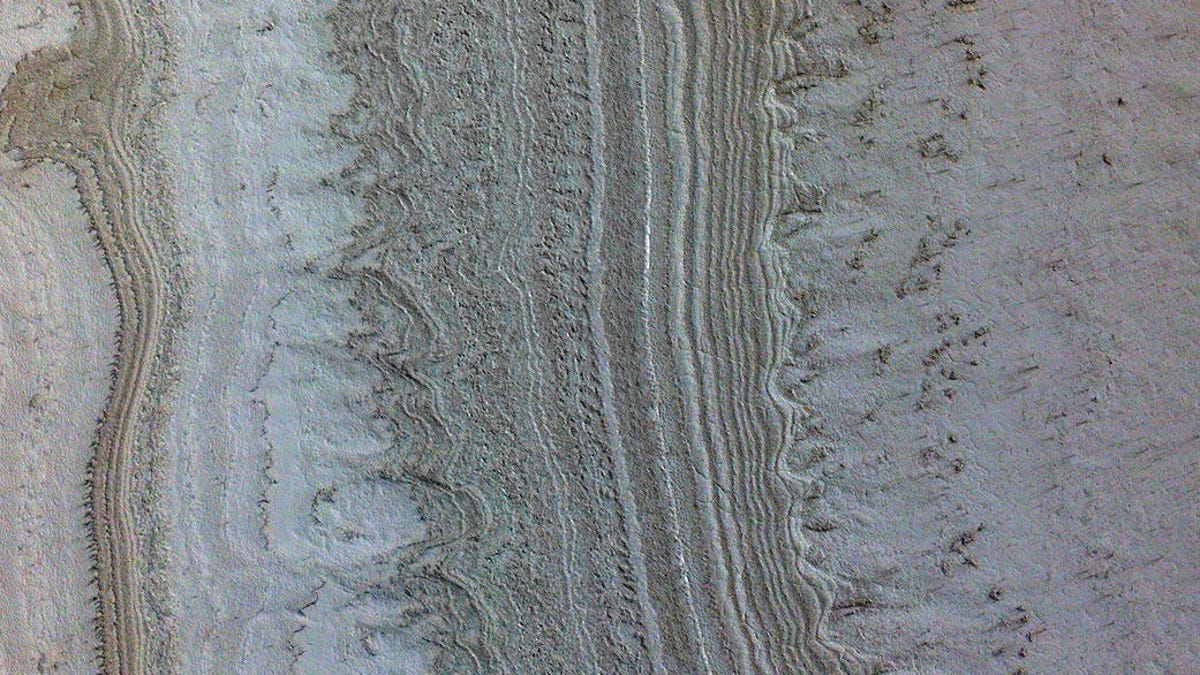

NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter captured this view of ice sheets at Mars' south pole.

Note to the adventurous: Your odds of ever getting to scuba dive in a hidden lake beneath the southern ice cap on Mars may have just turned to Martian dust.

In 2018, scientists using radar data from the Mars Express orbiter spotted what looked to be a salt water lake about a mile (1.5 kilometers) below the ice. But new research suggests what they saw was the same kind of dusty, volcanic rock that covers many a Martian plain.

A team led by Cyril Grima, a planetary scientist at the University of Texas Institute for Geophysics, put a virtual global ice sheet over a radar image of Mars. Volcanic plains at all different latitudes showed up looking the same way as the supposed lake under the south polar region.

The team surmised it's more likely that radar is showing volcanic rock beneath the ice than water that somehow remains liquid despite cold and dry conditions.

"For water to be sustained this close to the surface, you need both a very salty environment and a strong, locally generated heat source, but that doesn't match what we know of this region," Grima, who is lead author on a study published in Geophysical Research Letters, said in a statement.

The possibility of a Martian sub-polar water lake was already seeming less likely by 2021, when multiple studies, including one led by NASA, cast doubt on the idea, suggesting instead that the radar may be picking up a type of frozen clay.

"Science isn't foolproof on the first try," said Isaac Smith, a Mars geophysicist at York University. "That's especially true in planetary science where we're looking at places no one's ever visited and relying on instruments that sense everything remotely."

So ice fishing for Martian polar trout may be off the agenda for the coming decades, but there's still plenty more to explore on the red planet.

"I think the beauty of Grima's finding is that while it knocks down the idea there might be liquid water under the planet's south pole today, it also gives us really precise places to go look for evidence of ancient lakes and riverbeds," Smith added.

And one of those places just might hold a game-changing fossil that could alter humanity's perspective on life in the universe. Stay tuned.