Watch for Stunning Auroras as an Extended Solar Storm Smacks Earth This Week

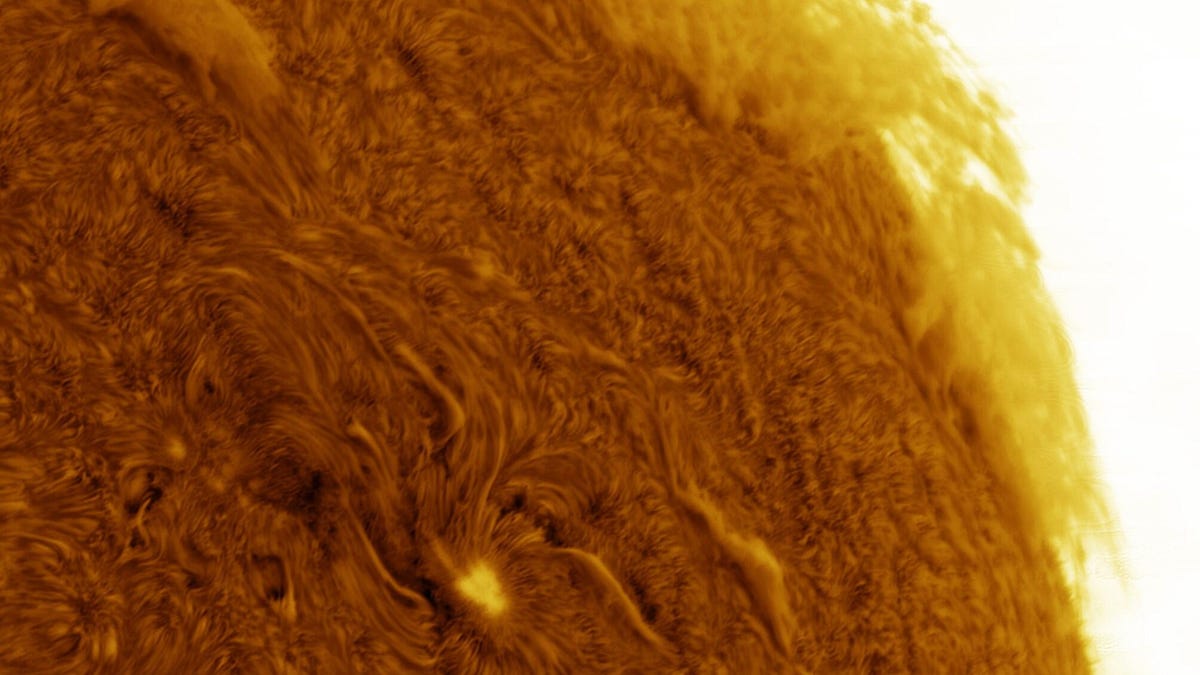

A view of an explosion in the sun's atmosphere, taken by photographer Martin Wise from Florida on July 15.

What's happening

Eruptions on the sun could trigger a geomagnetic storm on Earth this week.

Why it matters

Extreme space weather can disrupt radio communications and even affect the power grid. This time it's most likely that the main impact will be brilliant auroras.

The sun has been experiencing the stellar equivalent of gastro-intestinal distress over the past week, and now Earth is set to get blasted by a series of big burps from our local star over the next few days.

Forecasters from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Space Weather Prediction Center predict a series of minor and perhaps stronger geomagnetic storms from Thursday through Saturday as charged particles from multiple energetic eruptions on the sun, including one eruption described as a "solar tsunami," collide with our planet's magnetosphere.

The eruptions are what's known in heliophysics as coronal mass ejections, often gargantuan bursts of charged plasma from the sun's atmosphere that can disrupt radio communications, damage satellites and even affect the power grid on the ground in extreme cases when they collide with our planet.

More commonly, though, they create brilliant displays of the aurora borealis and aurora australis, also known as the northern and southern lights.

SPECTACULAR FILAMENT ERUPTION: A filament stretching halfway across the solar disk became unstable and erupted away from the Sun. Couple things to note: (1) A section of it twists (magnetic energy being released). (2) After the event two bright ribbons form - a two-ribbon flare! pic.twitter.com/d3GN6S5Dpy

— Keith Strong (@drkstrong) July 16, 2022

Unlike solar flares, which can also affect radio communications but travel at the speed of light and thereby strike our atmosphere with only a few minutes notice, CMEs move slower, taking several hours or days to arrive. CMEs often follow strong solar flares.

A particularly slow-moving CME was hurled outward from the sun on July 15 and is expected to hit Earth on Thursday, July 21. On top of this, holes opened up in the sun's corona earlier this week, sending even more charged plasma in our direction in the form of the solar wind. Also, on Wednesday a flare was followed by a wave of energy rippling through the sun's atmosphere that astronomers have dubbed a solar "tsunami," which could also produce another CME.

All these influences converging on our little planet have skywatchers excited.

"This geomagnetic activity might provoke auroral displays starting tonight (Thursday)," heliophysicist C. Alex Young and Raul Cortes write for EarthSky. "The stronger the storm the farther south the auroras might be observed."

Those at higher latitudes have already been reporting some pretty spectacular aurora sightings this week.

Last night was amazing!! The Aurora made a nice appearance in Summit, SD while thunderstorms to the east were simultaneously spitting out incredible CG lightning under a moon-lit landscape. I can’t believe I wasn’t dreaming!#sdwx #aurora #photography @TamithaSkov @NWSAberdeen pic.twitter.com/7q5MCLLCN6

— Alex Resel 📸 (@aresel_) July 19, 2022

There's been some hype in more sensational outlets about the potential dangers of this solar storm, but the bottom line is that we're looking at a minor to moderate geomagnetic storm over the next few days. This could cause some minor communications issues for mariners and aviators, and big satellite operators like SpaceX may want to cross their fingers that their constellations aren't affected.

For most people, though, the main effect will be the opportunity to see the dancing lights in the sky that let us know we're forever interconnected with the sun and its seemingly limitless power. Auroras may be visible as low as 55 degrees in geomagnetic latitude, which would include areas as far south as Idaho, New York and much of northern Europe.

It is, however, a reminder that much stronger geomagnetic storms are inevitable and threaten to do some real damage to our satellite-dependent communications networks and our power grids. As the solar cycle builds toward a peak in sunspot and flare activity over the next two years, the risk will intensify at a period of time when our presence in orbit is growing exponentially.

Not a bad idea to consider some redundancy for our power and communications needs going forward.

But for now get outside, enjoy the show and share your best aurora photos with me at @EricCMack on Twitter.