Earth May Have a Nearby Twin. Here's What It Could Look Like

Scientists imagine α-Cen Earth would have water, graphite, a ton of diamonds... and maybe life?

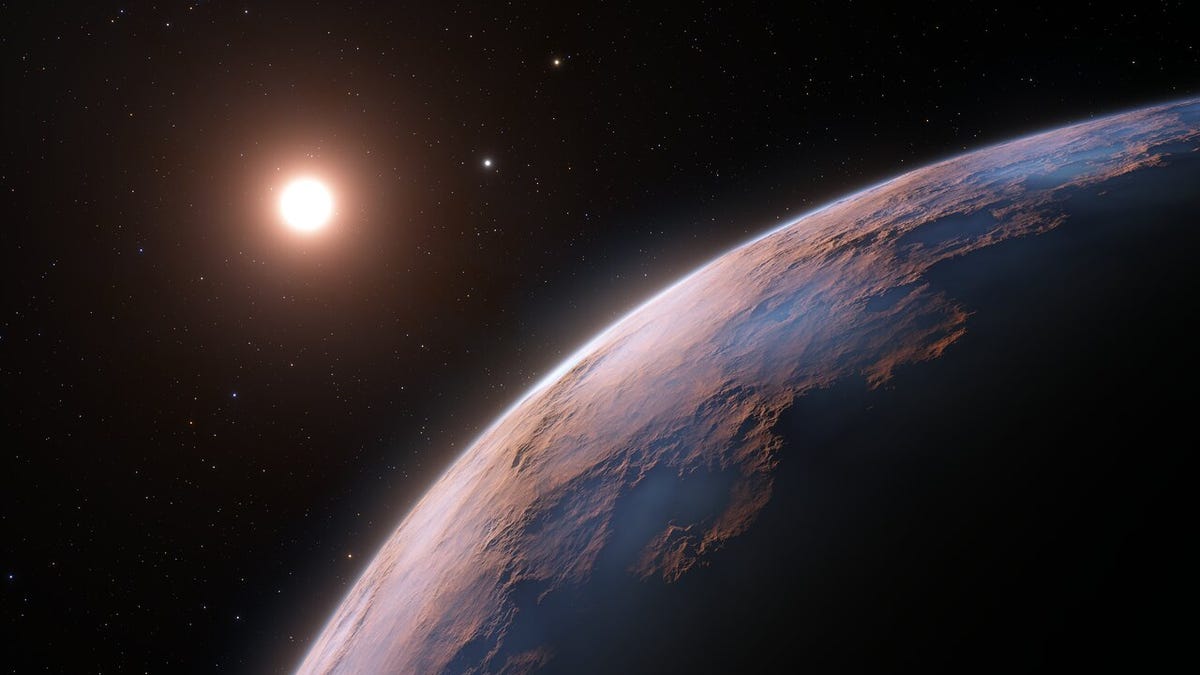

This artist's impression shows a close-up view of Proxima d, a planet candidate recently found orbiting the red dwarf star Proxima Centauri, the closest star to the Solar System and part of Alpha Centauri.

It may feel like Earth is alone at times, but the opposite is true. Approximately 10,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 (more than a septillion) planets call the cosmos home, and that figure doesn't even include all the rogue, starless ones.

Of course, a bunch are likely coated in wacky radioactive chemicals, made of pure gas or subject to scorching magma oceans -- but still, something like 300 million are expected to orbit sun-like stars, lie in their system's habitable zone, and if any are rocky, even resemble Earth. And another Earth might mean another lifeform.

If we're lucky, one of these Earth-twin contenders could be living a mere four light-years away, in our neighboring three-star system, Alpha Centauri. Holding onto that hope, scientists published a paper Thursday in The Astrophysical Journal that paints a fascinating picture of what such an alternate world might look like. If it's really there, that is.

The team calls it α-Cen Earth.

Based on data of what we know about Alpha Centauri, the researchers used numerical models -- some of which are pioneering for the field -- to create and measure a hypothetical, rocky, Earth-sized planet in the system's habitable zone. This region is basically the spot in a star system most likely to possess water and have "just right" conditions for life. For that reason, it's adorably deemed the "Goldilocks zone." Not too hot, not too cold, just right.

This illustration compares the Trappist-1 star system and the three planets in its habitable zone (in green) with our own solar system.

Strikingly, their models suggested α-Cen Earth would be pretty similar to our own planet. It'd have a mantle, or middle layer, dominated by silicates, and an interior with as much water storage capacity as Earth. The "other" Earth, however, might be a little more sparkly: A ton of graphite and diamonds, the study says, might be hanging out in its mantle alongside regular rocks.

But most surprisingly, and perhaps even most promisingly, the simulated α-Cen Earth appeared to exhibit an early atmosphere akin to Earth's during the Archaean eon, around 4 billion to 2.5 billion years ago. That's when life first emerged on our planet in the form of microbes.

On the flip side, though, α-Cen Earth would differ from normal Earth, the study says, because it'd likely have an iron core slightly larger than ours and a surface that doesn't abide by the theory of plate tectonics. This idea suggests Earth's surface is made of movable puzzle pieces which dictate how continents and oceans are arranged.

All things considered, the team's new study offers much more than a sneak peek into Earth No. 2. It serves as a stepping stone, both physically and metaphorically, for future exoplanet exploration. Not only do these models pave the way for understanding star-planet connections key in detecting habitability, but they also serve as a timely reminder that there are so many worlds are out there, just waiting for us to find them.

Lately, such a notion has been heating up with research into hyperspeed space sails that promise to take us to other star systems at 20% the speed of light -- we'd be able to reach Alpha Centauri in just 20 years with the devices -- and the trailblazing launch of the James Webb Space Telescope.

Though Webb has several astrophysical missions, a major one aims to search for habitable exoplanet atmospheres near sun-like stars. Just maybe, one day, it'll find the real second Earth.