How 'Dinosaur Fish' Stand on Their Heads

A preserved coelacanth is helping researchers tease out the secrets of an odd fish on the edge of extinction.

Coelacanths, also known as dinosaur fish, were thought to be extinct until a specimen was netted in 1938. These rare, primordial animals live in underwater caves, making them hard to study. So a team of scientists has gotten creative with a decades-old preserved specimen.

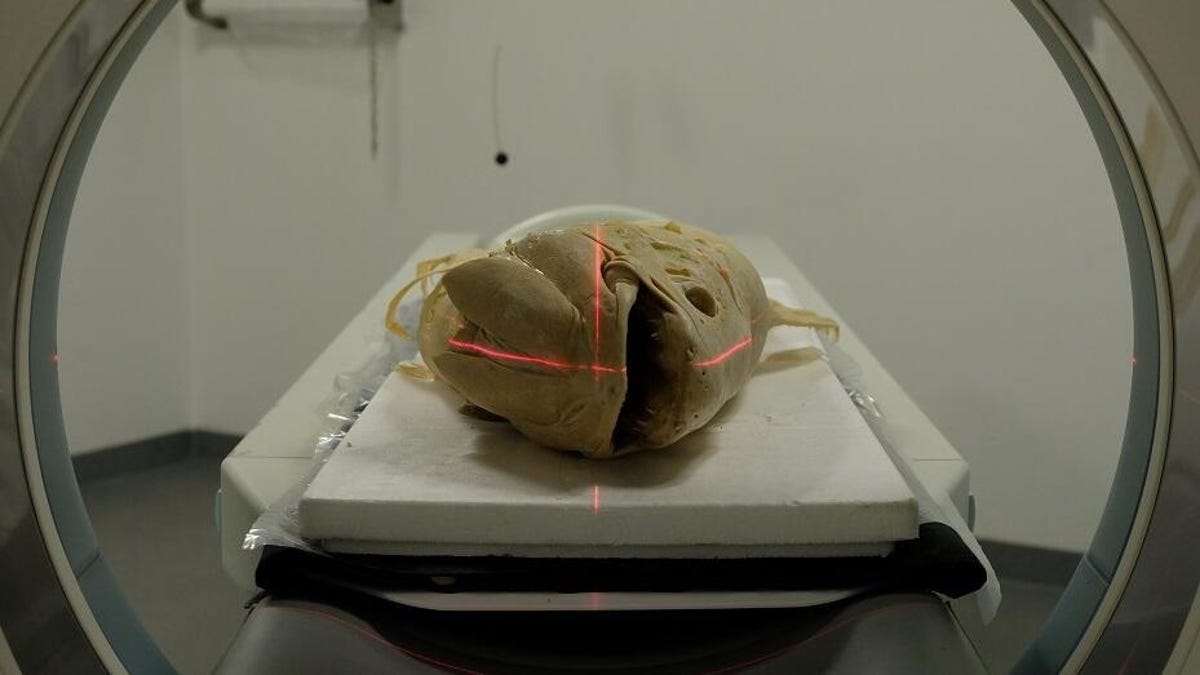

The fish -- known as "specimen number 23" -- had been hanging out in alcohol at the Zoological Museum in Copenhagen for 60 years. Researchers from the University of Copenhagen and Aarhus University took it out of its pickling juice and ran it through CT and MRI scanners to learn more about how the sea creatures work.

Biologists Peter Rask Moller (left) and Henrik Lauridsen pose with the Copenhagen coelacanth at the CT scanner.

The team has published a study on the fish in the journal BMC Biology.

"As many other coelacanth specimens have been dissected, its anatomy is no secret," University of Copenhagen said in a statement on Tuesday. "But very little is known about the fish's physiology – the way it functions."

The study helps explain the fish's unusual head-stand feeding strategy where it drifts along the seabed, head down, to catch prey. The researchers mapped out the fish's bones and fat.

"We discovered that the coelacanth has a special skeleton with a lot of bone mass in the head and tail, while there are almost no vertebrae. It's quite unique. The heaviest parts are at either end of the fish, which makes it easy for the fish to stand itself on its head," said co-author Henrik Lauridsen, a biologist at Aarhus University.

This CT image highlights the bone mineral density of the coelacanth specimen. That dense head structure helps it feed head-down.

Coelacanths have a long history on this planet. Fossil evidence of the fish dates back to over 410 million years ago.

The IUCN Red List, a catalog of threatened species, lists the West Indian Ocean coelacanth (Latimeria chalumnae) as critically endangered, one step up from being extinct in the wild. Learning more about the fish could help with plans to protect it. Capturing the rare animals for study could put more pressure on the species. That's a big reason why this research on the preserved coelacanth is important. It's a resource that's already available and the same techniques can be used on other specimens.

The researchers want to learn more about the secretive reproductive cycle of coelacanths. This fish stay pregnant for five years before birthing live young, but no one is quite sure where they have their babies.

"By analyzing the distribution of bone and fat in a fetus, we can probably find out at what depth fry are adapted to live," said Lauridsen. "This knowledge is also important in terms of preserving this critically endangered species – because when we don't know where they are, we can't know where to protect them."