Funky-Cute Echidnas Blow Snot Bubbles to Keep Cool in the Heat

Sometimes called spiny anteaters, echidnas have developed some fascinating ways to chill out in Australia.

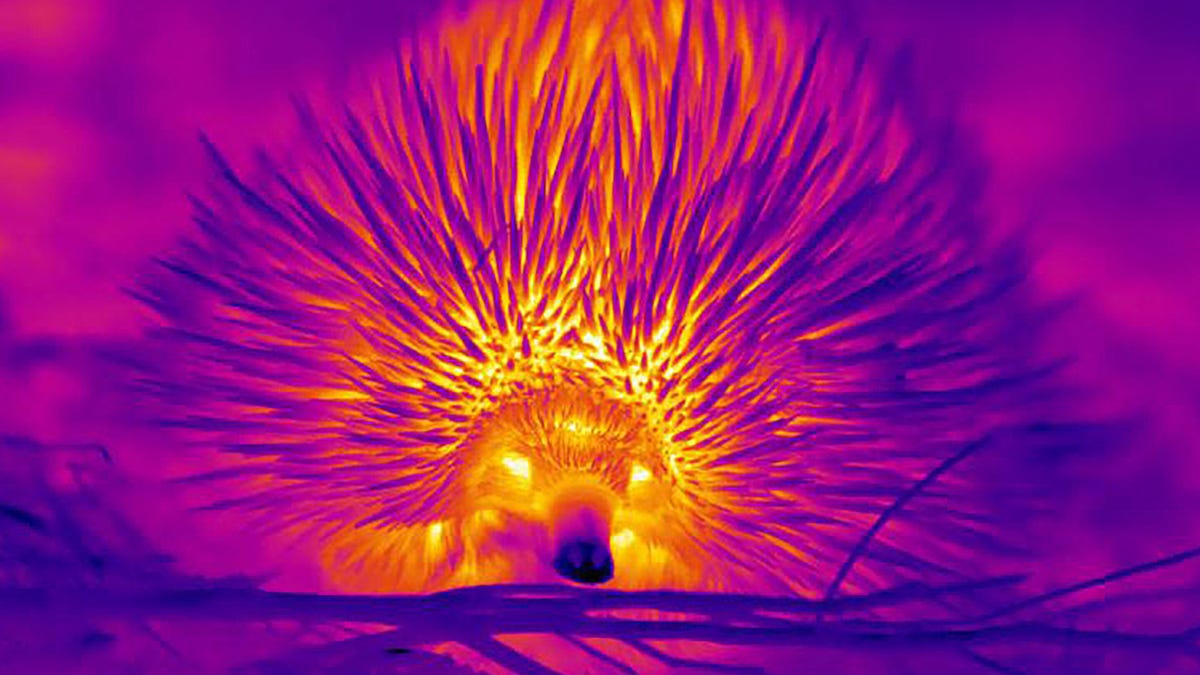

Researchers used thermal vision to investigate how echidnas cool themselves off.

Echidnas are magical little creatures. They're oddly cute, egg-laying mammals with quills. They're related to platypuses. Like many animals, they will likely face new stresses as the climate crisis continues to turn up the heat. New research is showing how short-beaked echidnas in Australia have unusual ways of keeping cool.

Curtin University researcher Christine Cooper specializes in native Australian birds and mammals and is the first author of a study on echidnas' thermal regulation abilities published on Tuesday in the journal Biology Letters. The work is helping scientists understand how echidnas might respond to a warming climate.

Cooper used an infrared camera to record thermal videos of wild echidnas. The animals blow mucus bubbles from their noses to dampen the nose tip. The researchers discovered how the moisture then evaporates and cools the echidna's blood. The animals' spines also act like flexible insulation that can be "closed" to retain warmth or "opened" to cool off. The spineless parts of their bodies, like the undersides, can also shed heat when needed.

"Echidnas can't pant, sweat or lick to lose heat, so they could be impacted by increasing temperature and our work shows alternative ways that echidnas can lose heat, explaining how they can be active under hotter conditions than previously thought," Cooper said in a Curtin University statement.

The study included 124 echidnas monitored over the course of a year. It had been thought that echidnas primarily dealt with dangerously high temperatures by changing their behavior, including becoming more nocturnal during the summer. As the paper notes, "Echidnas have a more sophisticated suite of thermoregulatory strategies than has been generally appreciated." That resiliency may be help the species survive in a warming world.