A super-Earth just discovered in our cosmic backyard might contain an atmosphere

Gliese 486 b is an interesting candidate when it comes to studying exoplanet atmospheres.

Gliese 486 b is incredibly close to its host star, with an orbital period of just 1.5 days.

About 26 light-years from Earth lies Gliese 486, a red dwarf star. These types of stars litter the Milky Way; they're basically everywhere. But we can't see any from Earth when we look up into the night sky, because they're just not very bright. Gliese 486 is no exception. However, if you have yourself a good enough telescope, Gliese 486 can't hide.

Astronomers, studying the star over a four-year period between 2016 and 2020, noticed periodic dips in its brightness -- the telltale signs of an orbiting exoplanet. In a study published in the journal Science on Thursday, researchers detail the discovery of the planet, dubbed Gliese 486 b. It's the third-closest exoplanet discovered with this method. Thousands of planets have now been discovered in our galaxy, but Gliese 486 b is particularly noteworthy because astronomers believe we may be able to study whether the planet has an atmosphere.

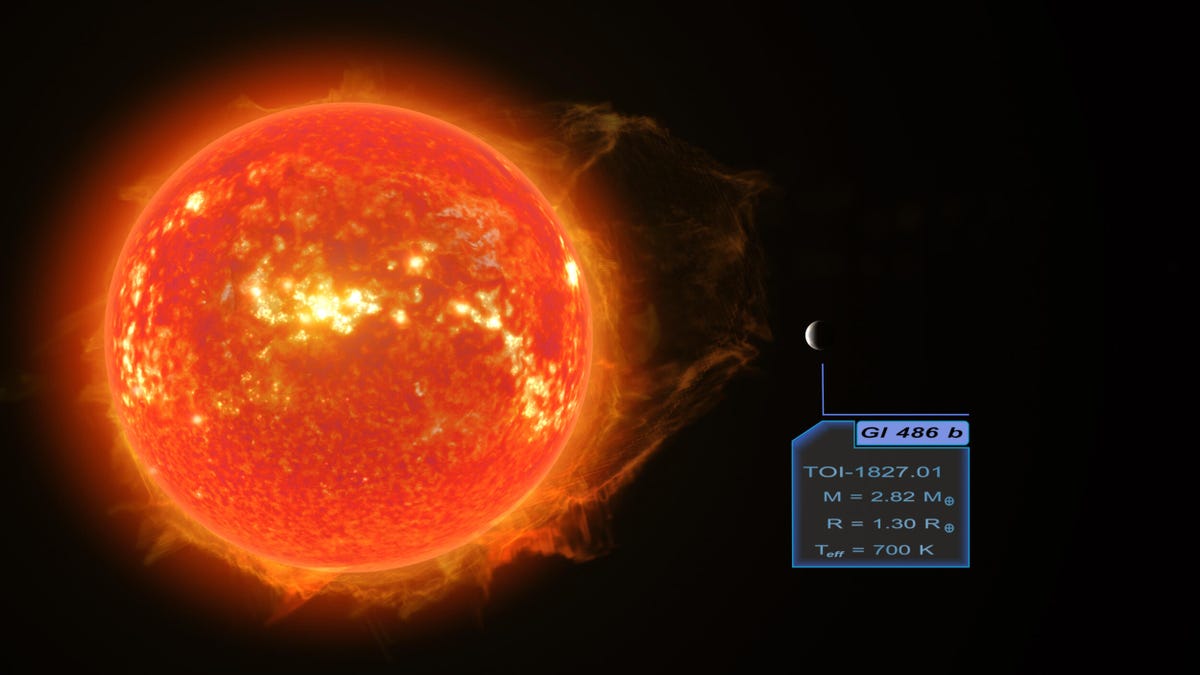

The rocky world is slightly larger than Earth but three times more massive (a so-called "super-Earth") and makes a full orbit of its parent star in less than 1.5 days. Data from two exoplanet-hunting missions, NASA's TESS, a space telescope, and the Carmenes survey, by Spain's Calar Alto observatory, which specifically looks for planets around red dwarfs, was obtained to study the newly discovered planet.

Though we've found a ton of exoplanets, they're not easy to see. Planets don't reflect a lot of light, so you have to find them indirectly. One way to do that is to look for dips in the brightness of a star, the "transit" method, which signifies a planet moving in front of the star. Another is to assess how a star's radial velocity changes, which happens when a planet is tugging on the star and it appears to "wobble" when observed. For Gliese 486 b, both methods were used -- giving researchers a powerful tool to define more of the planet's characteristics.

Hot damn.

The researchers write that Gliese 486 b isn't a hellscape planet made of lava, like some of the exoplanets we've found close to stars. Rather, its surface is a mild 800 degrees Fahrenheit, making it cooler than Venus but still toasty enough to melt lead. "Its temperature ... makes it suitable for emission spectroscopy and phase curve studies in search of an atmosphere," the team write.

Spectroscopy allows researchers to split light into its various wavelengths, which can tell them about the chemical composition of its atmosphere. It wouldn't be the first time we've been able to assess the atmosphere of a super-Earth, that honor goes to 55 Cancri e, but 486 b would be the closest yet and could give us clues about the planet's habitability.

There's no reason to think we'd find life there, but an atmosphere would certainly help. And with the recent discussions around "life" on Venus, perhaps it's worth investigating.

The much-delayed James Webb Space Telescope, which is slated to launch later this year, will also be able to observe exoplanets like this and begin to slowly peel back the cosmic curtain on the worlds lurking in deep space.

Follow CNET's 2021 Space Calendar to stay up to date with all the latest space news this year. You can even add it to your own Google Calendar.