Student Debt and the Racial Wealth Gap: Partial Forgiveness Alone Won't Solve This Crisis

Commentary: It's going to take more than $10,000 or $20,000 to fix this.

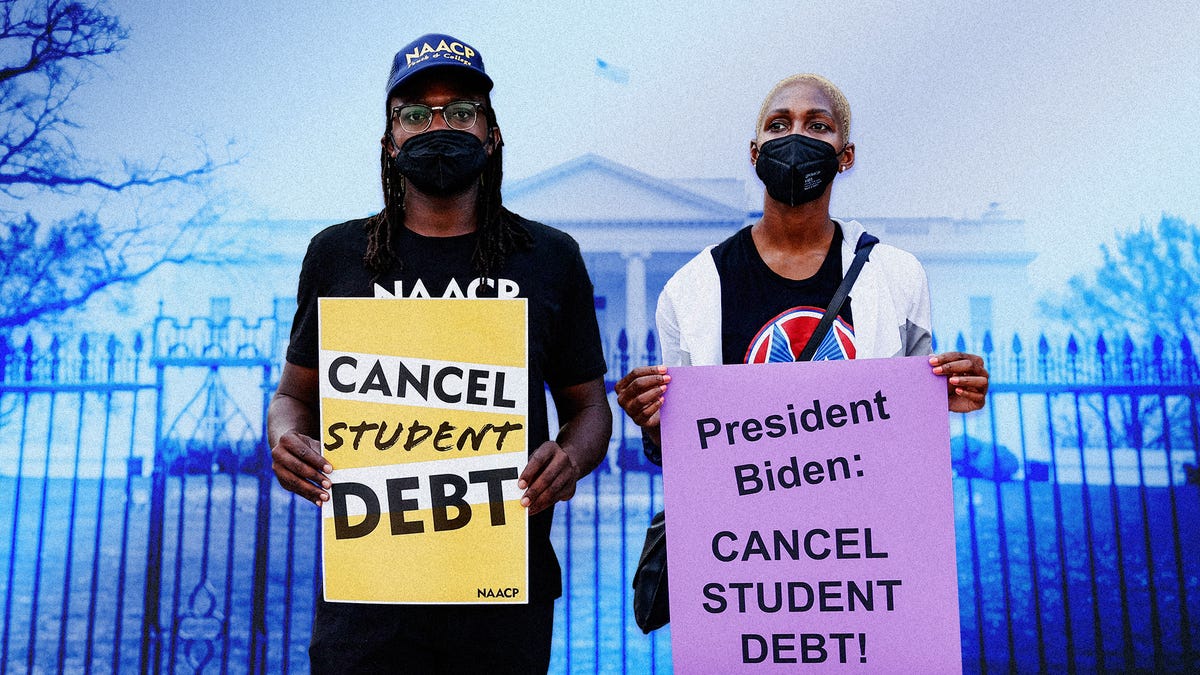

Right now, the Biden administration's student loan relief plan is on pause. Sadly, it's been blocked by a federal appeals court as it reviews allegations from six Republican-led states that the plan isn't legal and would deprive state-based loan companies of revenue.

That's just one of the many setbacks and objections that the student debt relief program has faced in recent weeks. In another lawsuit, which was denied, a conservative legal group in Wisconsin went after the White House for saying the plan could narrow the racial wealth gap and improve racial equity, thereby alleging the government had an "improper racial motive."

Really?

And all this political backfire over just partial relief for some borrowers. Imagine the uproar if all student debt was eliminated or if higher education was made free.

But this column isn't about how I want naysayers to buzz off. Instead, it's about how after this temporary order gets sorted out, we best turn our focus on fixing our broken US higher education system, starting by focusing on the most financially vulnerable and penalized of all borrowers: Black Americans.

The nation's $1.7 trillion student debt crisis puts a disproportionate burden on Black borrowers because of the racial wealth chasm. On average, Black households have about eight times less wealth than white households, and Black students borrow $25,000 more for higher education.

Because of greater financial need, Black people take out a larger amount of loans with the hope that it will pay off when they get a job following graduation. But the effect is cyclical -- higher loans mean they pay more compounding interest over time, and since they earn less on the dollar than their white counterparts, it's harder for them to pay back the loans than other groups (this is especially true for private loans, which can have higher interest rates than federal loans and minimal consumer protections). A 2019 study from Brandeis University found that 20 years after first enrolling in school, the average Black borrower still owed 95% of their original student debt. And according to the Brookings Institution, three times as many Black borrowers default on their loans compared with white borrowers.

Moving forward, we should center reform on racial inequities. In doing so, we have a better chance of not only helping this core group of struggling borrowers, but everyone who was sold a false bill of goods -- by school counselors, lenders, college administrators and, most of all, our elected leaders -- about the reality of an expensive college degree.

A system where people aren't saddled with student debt would benefit everyone. "A higher education is as basic as an elementary or secondary education nowadays," Senior Fellow Andre Perry of Brookings Metro said in an August interview with The Current. "Society needs its populace to be more highly educated. And so we need a system that treats it as much."

Why and how student debt reform should go further

The administration's loan forgiveness plan is an effort in the right direction. It vows to cancel up to $10,000 in federal student loan debt for borrowers earning less than $125,000 a year (or $250,000 for married couples), or up to $20,000 for low-income Pell Grant recipients.

But as my recent So Money guest Peter Dunn, a certified financial planner, stated: "This is essentially a short-term solution. It doesn't address the larger underlying issues in the US higher education system."

Most importantly, policy and financial experts say the move isn't enough to really help to narrow the racial wealth divide. In a conversation on my podcast with Jean Lee, president of the Minority Corporate Counsel Association, we discussed the impact of student debt on Black and marginalized groups. "The federal government is disproportionately really profiting from Black students because they tend to take out larger loan amounts than any other group," Lee said. "There's an opportunity for the government to certainly make a bigger difference."

Read More: Student Loan Debt Is Crushing Millennials' Financial Dreams

Carl Romer, a former research assistant at Brookings who coauthored the study Student Debt Cancellation Should Consider Wealth Not Income along with Perry, told me in an email that based on their findings, "The more student debt that gets canceled, the more ameliorative effect it will have on the racial wealth gap."

More debt forgiveness would be better for the current generation of borrowers, but where do we go from here? How do we ensure that the next rising college student doesn't borrow more than they can afford for a degree that won't necessarily lead them to a well-paying job? How do we avoid the next generation getting crushed by the burden of lifelong debt from skyrocketing tuition?

If our goal is to create a level playing field, here are some ways policymakers can narrow the racial wealth gap and address what has become a major social and economic crisis in this country.

Eliminate interest

The first step Lee suggested is for the administration to cancel all interest for Black borrowers. "Compound interest really adds up," she said. One study by JPMorgan Chase found that 13% of Black borrowers might never pay off their loans because the additional interest prevents them from being able to pay down the principal. Combine that with an overall rising cost of living and the fact that Black students face pay discrimination, which makes upward mobility even more inaccessible.

Ballooning interest rates have a long-lasting negative impact on wealth inequality. I found one analysis showing how a borrower with a federal loan balance of $28,000 and a 5.8% interest pays an extra $80 per month, meaning that if interest were eliminated, they could save roughly $9,000 over the course of a decade. Imagine if someone could invest that money in a retirement fund or it could go toward a down payment on a home instead.

Consider wealth, not income

To qualify for the current debt relief plan, borrowers must earn under a certain income threshold. But how much someone earns -- without any context of their financial obligations, their generational wealth or how much total debt they actually hold -- is an arbitrary metric.

Lee made an effective argument on my podcast that student debt relief shouldn't be based on income levels. For example, if someone is making above the $125,000 income cap, it doesn't mean they can afford to repay their debt, particularly as inflation continues to make it harder to afford essentials. Plus, the reality after graduation is different for marginalized households. She noted that Asian Americans, Black Americans, Latinos and Indigenous groups often have more than one generation within a home, supporting not only their own family but also their aging parents. "What if you have three generations living in a home, and you're the sole breadwinner, or everyone is relying on you?" Lee posited.

Student debt cancellation reform should consider wealth instead of income, according to Perry and Romer. "Policies should be evaluated by their expected impact on people at different wealth strata," Romer told me. "Because Black families have lower wealth than non-Black families, they are less able to help with the costs of high education. This contributes to Black students dropping out of college for cost reasons, and leaves Black households more likely to have student loans with no corresponding increase in income," Romer said.

For context, more than half of Black households with student debt have zero or negative net worth. The primary issue is that Black people are in an overall more precarious economic position, with less intergenerational wealth because of the history of discrimination. That means Black students with debt are less likely to surpass the net worth of their parents' generation.

Expand access and funding for public colleges

While higher education still correlates to greater lifetime earnings, that equation isn't so simple for Black borrowers. The idea that a degree will "pay off" is more questionable if you're still encountering discriminatory obstacles in housing, employment and other arenas once you graduate.

Private institutions are on average about 282% more expensive than public institutions. But many community colleges are subsidized, making them low-cost alternatives, with an associate's degree often serving as a stepping stone to pursuing a bachelor's degree elsewhere. Perry argued on The Current that the subsidies already in place in the public sector should be expanded so that the cost of attendance in four-year public universities is free.

Ultimately, tuition reform should make public higher education degrees more financially accessible, which would eliminate the need for Black students -- and all students -- to take out loans in the first place. And it would mean that young people, especially from the most disadvantaged groups, would no longer be penalized for wanting to advance their education.