Want to be better at math? Electric shocks could help

In ongoing research with children and adults, an Oxford University researcher finds that stimulating the brain with low-dose electrical currents could help improve learning.

In a room at Oxford University in England, children between the ages of 8 and 10 are working on math problems on computers while being administered electric shocks by senior research fellow Roi Cohen Kadosh.

OK, they're not really getting shocked, but they are getting a steady stream of low-current electricity delivered to their brains.

The procedure they're undergoing is known as Transcranial electrical stimulation (tES), and it's one of the most recent brain stimulation techniques to come about in a long history of electrical currents used to manipulate the brain. Unlike earlier electroshock treatment programs, which tended to placate people with mental disturbances, the goal of this work is to help people with learning disorders overcome their difficulties, and to help others learn better generally.

The kids spend 30 minutes twice a week being studied by Cohen Kadosh as part of his ongoing research into how electrical currents could help learning.

Cohen Kadosh just published a report in Frontiers in Human Neuroscience that details his work with two adult individuals suffering from Developmental Dyscalculia (DD), a condition in which people have difficulty learning math and processing numbers. DD affects nearly 7 percent of the population, according to the report.

Cohen Kadosh found that when he attached an anode to the area of the brain known as the left posterior parietal cortex and a cathode to the right side of the same region and applied the mild current, learning skills improved. Interestingly, when he reversed the electrical conductors, the treatment didn't work.

The experiment involved assigning each number from 1-10 a specific symbol. Then Cohen Kadosh asked the two participants to evaluate pairs of symbols and say which was bigger numerically. Only the study participant who got left-to-right brain stimulation was able to go from distinguishing pairs that were sequential to distinguishing pairs that were non-sequential.

Granted, two people is clearly a tiny sample group, but the findings dovetail with research Cohen Kadosh reported in the journal Nature in May of last year that showed that electrical stimulation could increase learning even in people without learning disabilities.

In that study, 13 Oxford students were given a type of electrical stimulation known as TRNS, or transcranial random-noise stimulation. Compared with a control group that got no electrical stimulation, they performed faster at both memorizing mathematical facts and executing complicated equations. Six months later, the "charged" group still performed 28 percent better than the control group.

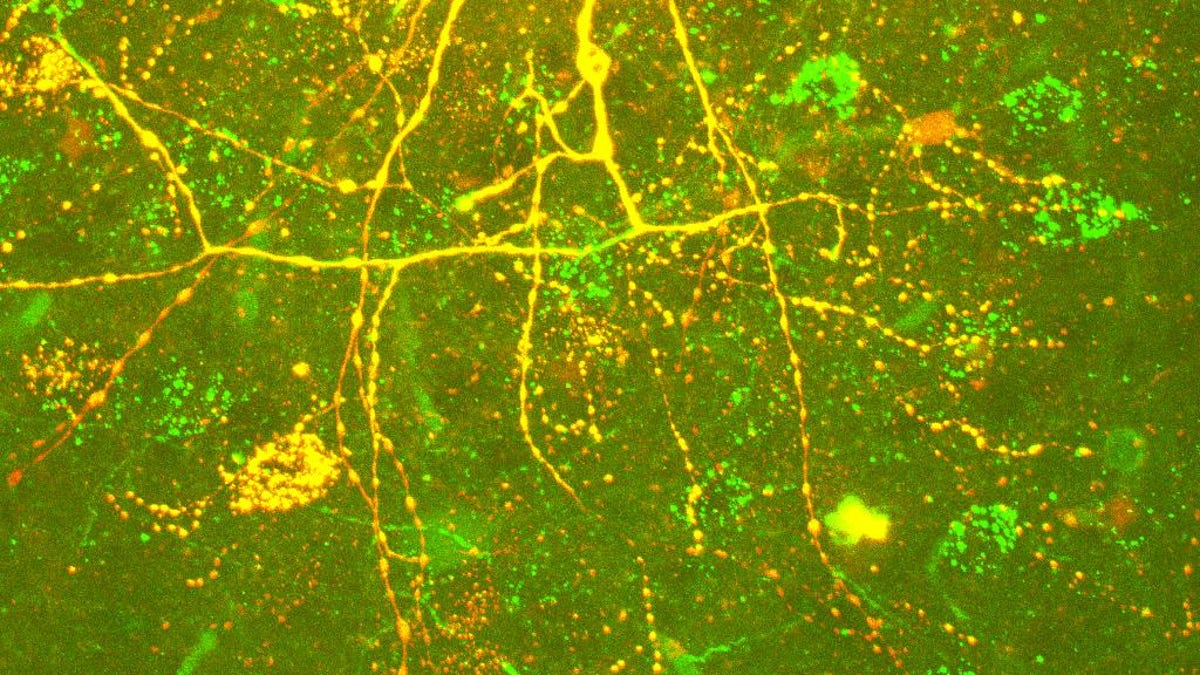

In the studies, people wear a tight-fitting cap through which current supplied by a 9-volt battery is passed. The current can be directed to specific parts of the brain and allegedly feels akin to having a baby tug on your hair -- gently. The theory behind why the research works is that the current lowers the threshold neurons have to reach before firing, and firing neurons help the brain transfer information, a key component of learning.

Brain-stimulating devices like the Focus headset are already available commercially, but Cohen Kadosh recommends caution. "It's early days but that hasn't stopped some companies from selling the device and marketing it as a learning tool," he told the Wall Street Journal. "Be very careful," he added. Still, if you want to disregard that advice and can't afford a new brain-boosting cap, you can learn how to make your own with a hot glue gun, two sponges, and few other doodads in this helpful YouTube video: