Sleuths uncover hidden trove of Isaac Newton's world-changing Principia

"We felt like Sherlock Holmes."

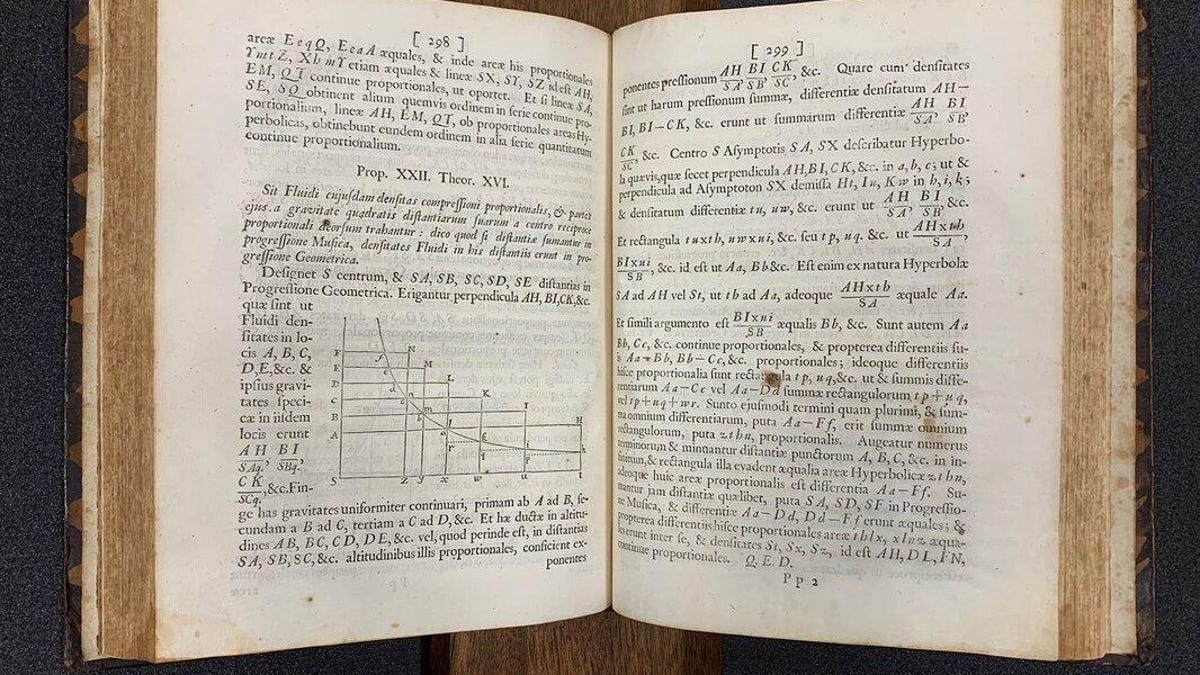

Caltech's copy of the Principia, owned in the 18th century by French mathematician and natural philosopher Jean-Jacques d'Ortous de Mairan. More recently, it was in the collection of Caltech physicist Earnest Watson.

A decade-long international search by two dogged historians has led to new revelations about one of the most groundbreaking science books ever written: Isaac Newton's 17th century Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica (Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy), which is viewed as seminal to the development of modern physics and astronomy.

The book, published in Latin in 1687 and known colloquially as Principia, lays out in mathematical terms principles of time, gravity and the forces of motion that have guided the development of modern physical science. Not exactly the light stuff of beach reading, and it's long been assumed the book's abstruse contents limited readership of the first edition to a small, select group of expert mathematicians.

But a Caltech history professor and one of his former students have uncovered copies of the first edition in 27 countries, doubling the number counted in the most recent census 70 years ago. Annotations filling those found volumes suggest the heady text's early run reached a far broader and more varied readership than previously thought -- in England and beyond.

"One of the realizations we've had is that the transmission of the book and its ideas was far quicker and more open than we assumed, and this will have implications on the future work that we and others will be doing on this subject," said Mordechai Feingold, a professor of the history of science and the humanities at Caltech. Feingold has for years studied the work of Newton, one of the most influential scientists of all time.

Feingold and former student Andrej Svorenčík traced copies of the book around the world, from the UK to Ukraine, Slovakia to South Africa, Russia to Japan, and detail their findings in a study published in the journal Annals of Science.

Isaac Newton's ground-breaking science book Principia.

"We felt like Sherlock Holmes," Feingold said of the pair's literary quest.

The last census of Newton's Principia, published in 1953, identified 189 copies. The new Caltech survey counts 386 copies, including 91 auctioned volumes and versions found in libraries and private collections. The study details each copy of Principia tracked so far -- its place of origin and provenance, how it was bound, and notes filling the margins that might shed light on when and how widely Newtonian ideas really started to take hold.

The findings, write Feingold and Svorenčík, "necessitate a major refinement of our understanding of the contribution of Newtonianism to Enlightenment science."

The clues largely rest in margins crammed with words and symbols handwritten by readers who once held the now faded books and pondered the formulas and theories that filled their pages.

"When you look through the copies themselves, you might find small notes or annotations that give you clues about how it was used," says Svorenčík, now a postdoctoral scholar at the University of Mannheim in Germany. "You look at the condition of the ownership marks, the binding, deterioration, printing differences..."

The global search grew out of a paper Svorenčík wrote for a class taught by Feingold. It looked at the distribution of Principia in Central Europe, where Svorenčík is from. But when Svorenčík's research turned up more copies than expected, Feingold proposed they take the search global.

"An early 'aha' moment came when I finished checking German library catalogues," Svorenčík said. "The previous census reported just three copies in Germany, but I found almost 20 copies (we report 21 copies in Germany including missing/stolen ones). That meant that there were substantial gaps in the previous coverage and many copies could and actually were found."

The pair calls their census preliminary and believe more undocumented copies exist in public and private collections. They estimate that more than 600 copies of the book's first edition, and as many as 750, were printed in 1687. In 2016, a first edition sold for $3.7 million, a record for a science book.

"It is our hope," the historians say in the study, "that publishing an interim report might yield information regarding other copies -- from private owners, book dealers and scholars -- so that a more comprehensive census might be attempted."