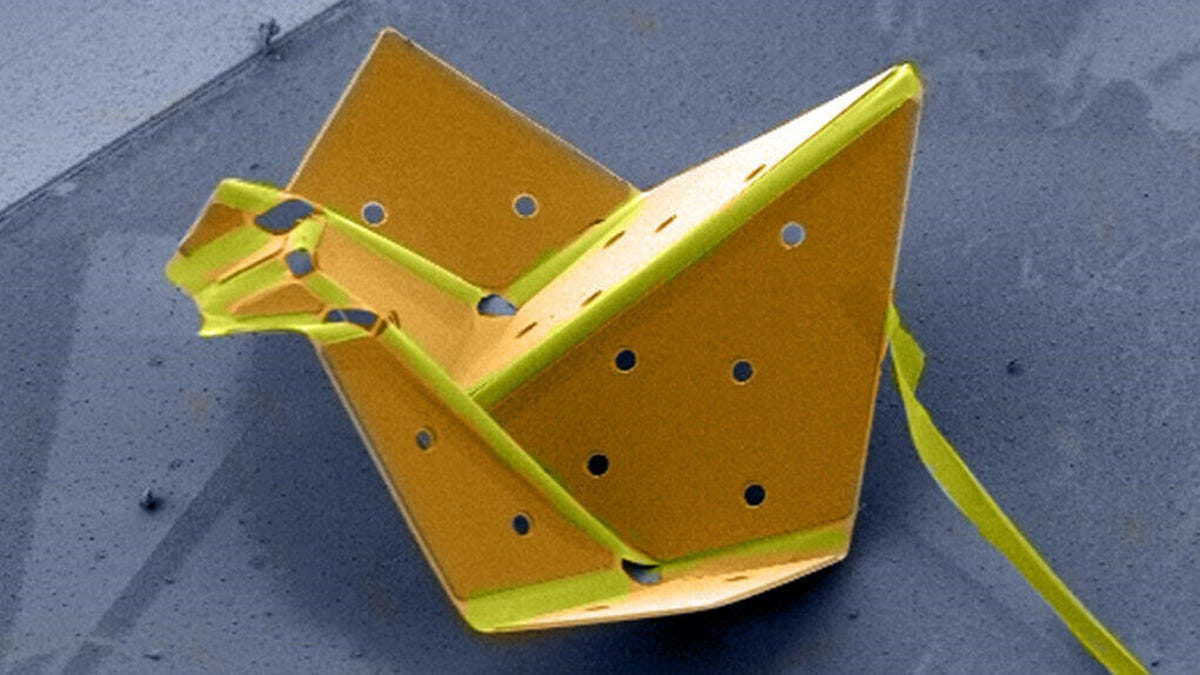

See the world's smallest origami bird fold itself into nanoscale art

The miniscule bird is a triumph for nanotech.

Scientists and engineers have previously taken robotics inspiration from origami, the art of folding flat paper into 3D objects. But a new creation is shrinking the idea down to nanoscale size.

On Wednesday, a team led by researchers at Cornell University unveiled what they believe to be the world's smallest self-folding origami bird. They published a paper on the work in the journal Science Robotics this week.

The tiny scale of the bird is hard to wrap your mind around. Co-author Paul McEuen of Cornell compared the nanoscale bird with a regular piece of paper: "One thing that's quite remarkable is that these little tiny layers are only about 30 atoms thick, compared to a sheet of paper, which might be 100,000 atoms thick."

Cornell released a video explaining the process and showing the origami in action, folding itself from flat into a dainty bird.

The nano-origami responds to voltage and can fold and retain its new shape. It can also be unfolded and refolded thousands of times. The bird has some novelty to it, but the same technology can be applied to other shapes.

The researchers are focused on developing smart nanobots that could be used for medical treatments. Cornell suggests one possibility would be "nano-Roomba-type robots" that target infections.

"We've learned how to build complex systems and machines at human scales, and at enormous scales as well," McEuen said. "But what we haven't learned how to do is build machines at tiny scales. And this is a step in that basic, fundamental evolution in what humans can do, of learning how to construct machines that are as small as cells."