It's alive...again! Scientists waking up 30,000-year-old 'giant' virus

A French team plans to wake up its second ancient virus in two years to study its genetic structure. Have these scientists never seen a zombie movie?

Bringing a 30,000-year-old virus back to life sounds like the plot of a real-life horror movie. So if you were scared by the incurable virus in the movie "28 Days Later," you might want to stop reading right now.

Scientists who discovered a prehistoric virus called Mollivirus sibericum in the Siberian permafrost plan to give the virus its first wakeup call since the last Ice Age (after first verifying that it can't harm humans and animals, thankfully). It's hoped the study could shed insight into ancient dormant viruses that could, it's feared, get another chance at spreading as permafrost retreats due to climate change.

The team, from the French National Centre for Scientific Research, announced its plans in a study published Tuesday in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) journal.

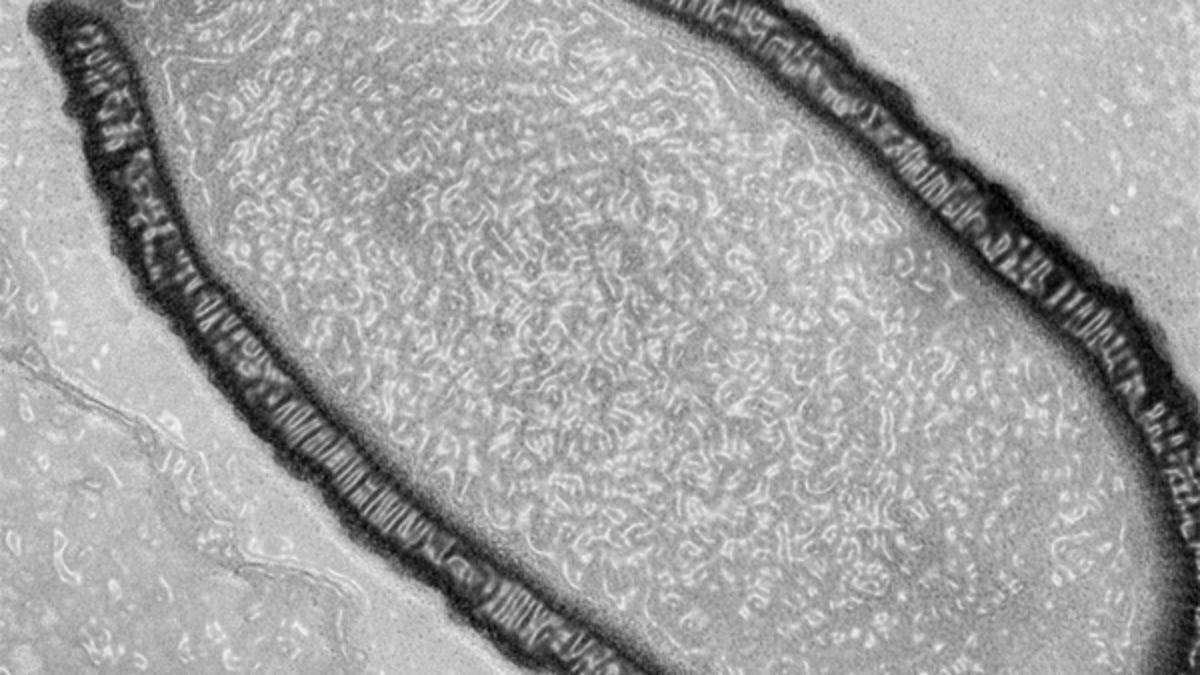

The virus is classified as a "giant" virus because it's visible by light microscopy. Mollivirus sibericum carries a complex genetic structure that houses more than 500 genes, according to the study's abstract. The influenza virus, in comparison, has only 8 genes.

The same team that discovered Mollivirus sibericum found another 30,000-year-old virus, Pithovirus sibericum, in the same Russian permafrost. As described in PNAS last year, those scientists revived a sample of Pithovirus sibericum in safe lab conditions and determined it was still infectious, though it only affects amoebas.

These cases raise concerns about such viruses in the context of melting permafrost.

Jean-Michel Claverie, an evolutionary biologist from the Structural & Genomic Information Laboratory at the Mediterranean Institute of Microbiology in Marseille, France, and co-author of the PNAS study, told AFP that the permafrost came from a stretch of land that contains valuable mineral resources such as oil. He noted that industrial exploration of this and similar sites is sure to continue as the ice continues to melt, and that could disturb undiscovered pathogens.

Claverie said it's possible that particles of these and other unknown viruses lurking in the permafrost "may be enough, in the presence of a vulnerable host, to revive potentially pathogenic viruses."

He added, "If we are not careful, and we industrialize these areas without putting safeguards in place, we run the risk of one day waking up viruses such as smallpox that we thought were eradicated."

OK, I'm officially scared now. Somebody hold me.