NASA wants to catch the solar wind to sail through space

The space agency begins testing a revolutionary new sail that aims to harness solar wind for propellant-free propulsion.

The edge of the solar system is a long way away. It took Voyager 1, the only human-made object to travel beyond the edge of the solar system (a barrier called the heliopause), 35 years to get there. New Horizons is expected to reach the heliopause in 2047, a total travel time of 41 years.

With its new propellant-free propulsion technology, called E-Sail, NASA plans to harness the solar wind and reduce that travel time drastically.

"Our investigation has shown that an interstellar probe mission propelled by an E-Sail could travel to the heliopause in just under 10 years," engineer and principal E-Sail investigator Bruce Wiegmann said in a statement. "This could revolutionise the scientific returns of these types of missions."

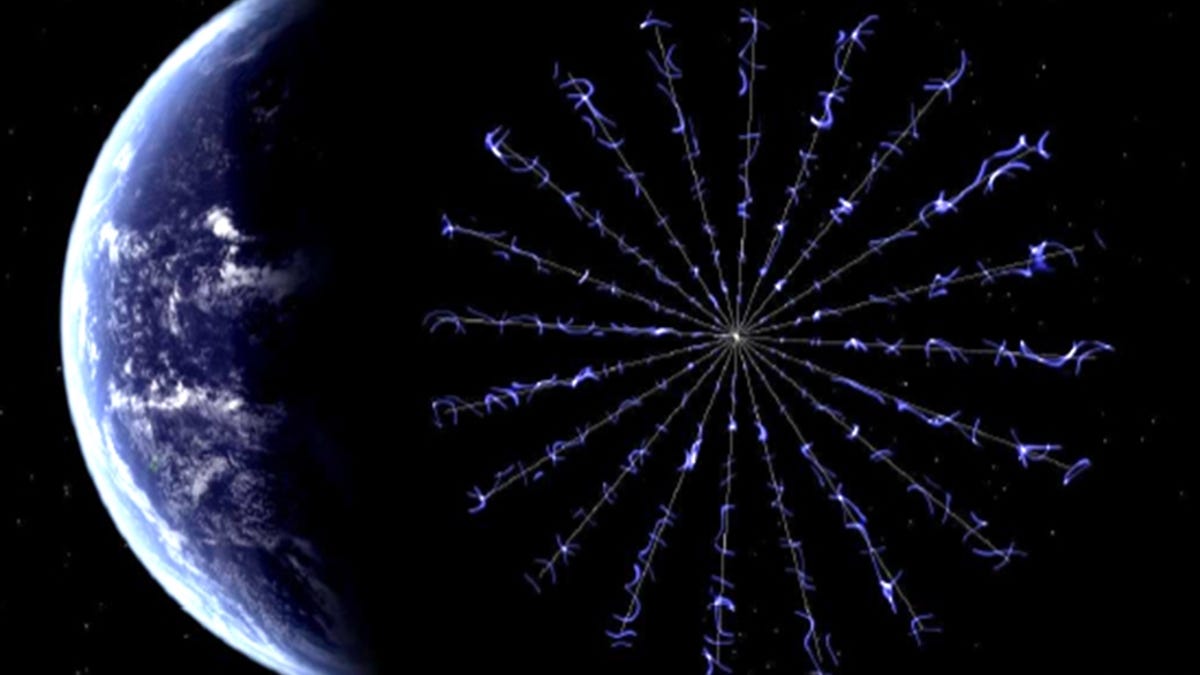

The Heliopause Electrostatic Rapid Transit System E-Sail doesn't look much like a sail at all -- more like a giant naked umbrella made of 10 to 20 aluminium spokes, protruding from the centre of the spacecraft. Each of these spokes is extraordinarily thin, just the width of a paperclip, and very long, about 20 kilometres (12.5 miles). These would be pulled into position by centrifugal forces caused by the slow rotation of the craft.

And it doesn't work like a terrestrial sail that is pushed by the wind itself.

"The sun releases protons and electrons into the solar wind at very high speeds -- 400 to 750 kilometers per second," Wiegmann explained. "The E-Sail would use these protons to propel the spacecraft."

The E-Sail's positively charged spokes would repel the protons electrostatically, which would in turn propel the craft. This is currently being tested in NASA's High Intensity Solar Environment Test system. This is a controlled plasma chamber that simulated plasma in space, and the team is testing the rate of proton and electron collisions with a positively charged stainless steel wire, which will degrade very little and allow for longer testing.

The plasma chamber where the wire is being tested.

There are several challenges involved in using the sails for propulsion. This has been demonstrated with the solar sail, a similar concept that uses light for propulsion. One of these is how far it can travel: At about 5AU (1AU is roughly the distance between the Earth and the sun) from the sun, light energy dissipates, and acceleration stops.

With the HERTS E-Sail, this could be less of a problem. The wires generate an electric field, the size of which increases the farther it gets from the sun. At 1AU, it would be around 600 square kilometres (232 square miles). At 5AU, it would be around 1,200 square kilometres (463 square miles). This would in turn increase its acceleration range. And, of course, it uses protons instead of photons.

"With the continuous flow of protons, and the increased area, the E-Sail will continue to accelerate to 16-20 AU -- at least three times farther than the solar sail," Wiegmann said. "This will create much higher speeds."