Why You Can Trust CNET

Why You Can Trust CNET Legal end of an era

A flea-market discard reminds us the long reach of short-sighted lawyers. Who owns my daughter's heritage?

My grandparents lived very long lives. My mother's father was born in 1893, grew up on a sheep ranch in Australia, fought for the British in World War I, suffered numerous life-threatening calamities and collisions as a semi-professional adventurer, and lived 86 years. My father's parents both lived to the age of 96. And my mother's mother lived to be more than 100 years old. She was a professional musician who played in the big bands, backing movies like Abbott and Costello's Here Come the Co-eds and played most famously in Phil Spitalny's Hour of Charm All Girl Orchestra, chronicled in the book Swing Shift. (Sadly that book was written after the memories of most of the sources had begun to degrade.)

When I was a boy and visited my grandmother in her Manhattan apartment, the prominent photograph in the kitchen was an 8x10 glossy photo that was to become the trademark image on many releases by Columbia Records. Though 20 years older than me, I remember how spectacularly black-and-white that professional photo appeared. It was quite some surprise, then, when I returned home one day to find a version of that photo pasted on the front cover of a multi-record set. Years of glue and sun had turned the photo on the album brown-and-yellow, but I could see clearly what the half-tone process had blurred--the proud faces of my grandmother and her sister backing the horn section with their shiny trombones. The albums came from my mother-in-law, who had seen the set at a flea market and bought them as a surprise for me.

It has been many years since I've owned a phonograph, and many more years since I or my family had access to one that would play a 78 rpm recording, the standard of the 1940s. Nevertheless, it gives me joy to have this physical relic of a bygone time when my grandmother was part of a momentary cultural phenomenon. And now that the records have been sitting in our dining room for months, I'm beginning to wonder just what they might sound like.

Last week I heard about a new technology for playing unplayable records developed by Carl Haber called IRENE. The technology scans the surface of a (usually unplayable) record and then digitally reconstructs the sound based on image analysis. In the words of the story:

Haber got the idea for this setup a few years ago, when he was driving to work and listening to NPR. He heard a report on how historic audio recordings can be so fragile that they risk being damaged if someone plays them by dragging a needle over their surfaces. It made Haber wonder if he could get the sound off old recordings without touching their delicate surfaces.

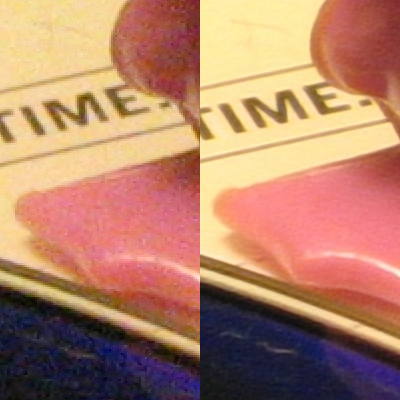

Too cool! But even more cool is something I know from signal processing technology: If one has multiple correlated signals (such as multiple copies of a record), one can use those multiple signals to get a higher-resolution version than any of the individual signal. Look at this pair of photos from a Wikipedia artcile on Super Resolution:

Astronomers use techniques like this to coax some amazing astrophotos from simple Webcams. What might my records sound like if I bought multiple copies from the many auctions I've seen on eBay, image them with IRENE, and then stack them to achieve a result that might even sound like the orchestra did the day they recorded the original master?

Unfortunately, the licensing agreement published on the record forbids me to do so.

The RESTRICTED USE NOTICE (capitals in the original) clearly states:

These records are manufactured and sold under United States Patents Nos 1625705 and/or 1702564 (and other patents pending) and are licensed by the manufacturer only for non-commercial use on phonographs in homes. All purchasers and users are notified that these records may be used only for non-commercial purposes on phonographs in homes.

So it would be illegal to take these records either to the Lawrence Berkeley Laboratories (where IRENE is being developed) or to the Library of Congress (where it is being evaluated), since neither is a home. And it would be illegal to use IRENE because that is not a phonograph. Talk about double jeopardy! So what is the lesson I should teach my daughter? That it's OK to ignore the law? Or that it's OK to abandon one's heritage because of a short-sighted system based on perpetual agreements? I believe that the longer, richer, and fuller lives we live, the more important it is that we share our lives liberally with the generations to come. That is the lesson I hope to teach.