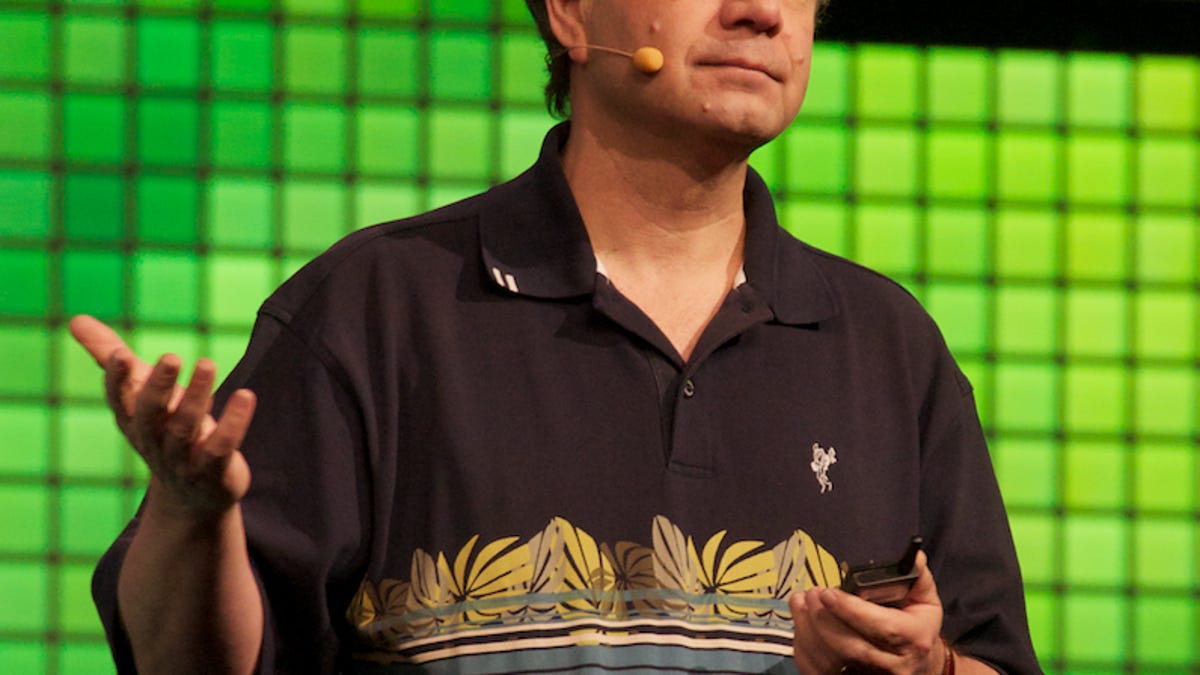

GDC: Sid Meier and his mind games

Game developer and guru tells developers that if they want to create the next best seller, they need to get inside the player's head.

SAN FRANCISCO--Legendary game developer Sid Meier took to the stage at the Game Developers Conference with a simple message to those who want to create the next best-selling title. The secret of making a great game, Meier said, is to get inside the player's head.

Psychology was never something Meier studied prior to getting into gaming. But as he explained to a crowd of developers at his keynote speech Friday, such a big part of game design ends up trying to figure out how the player will react to the things developers put in their games. Yet, as Meier explained, gamers are often a fickle beast. When good things happen in a game world, they often consider it their own doing, or accomplishment. But when something bad happens, they're quick to blame it on the developer.

The most obvious examples of this are in real-time strategy games, like Meier's own Civilization series. Meier said that players often overlook the logic within a game world in place of how they feel it should play out in fairness.

In his example, it was game testers of 2008 title Civilization Revolution who did not understand that they might lose a battle where they had the enemy outnumbered. Meier and the other developers had to build in a system that would remember past battles, so that the player was more likely to win a second battle after losing the first. This was to keep a player from experiencing too much disappointment or frustration.

The larger solution to user frustration, Meier said, is to add difficulty levels, something he admitted being wrong about just a few years ago. "In the past I said four difficulties were perfect...I was wrong about that. We need nine." Meier did this in his hit game Civilization 4, which celebrates its five-year anniversary later this year. As Meier explained it, offering more paths for a player to go through will plant a seed in their mind of "what if," as in "what if I try this battle or part of the story again. Will it be different?"

Meier urged developers not to spend too much time on these different paths though, at least if they're trying to save money and time. "No matter how good the graphics are, and how good your technology is, the player can always imagine something more compelling and more dynamic. Often we don't have to show everything that's happening in the game." Part of that, Meier said, is to tap into knowledge people are already bound to know from outside of a game. "This worked with Pirates," Meier said about his 2004 game title. "If [a player] sees a swordsman with a curly mustache, they probably know it's a villain they have to fight. So we don't need a whole lot of background on how he got there, or what his childhood was like."

But what about creating new experiences for things players have never seen before? Meier's answer to that was simple, in something he calls the "unholy alliance," an unspoken agreement players and developers make with every game they play. "I'm going to pretend certain things exist, and so are you to make this a better experience," he said. Followed shortly by, "this is an idea I should have trademarked."