For the German election, no fake news is good news

Compared to the US, Britain and France, Germany’s national election looks downright boring. That’s a good thing.

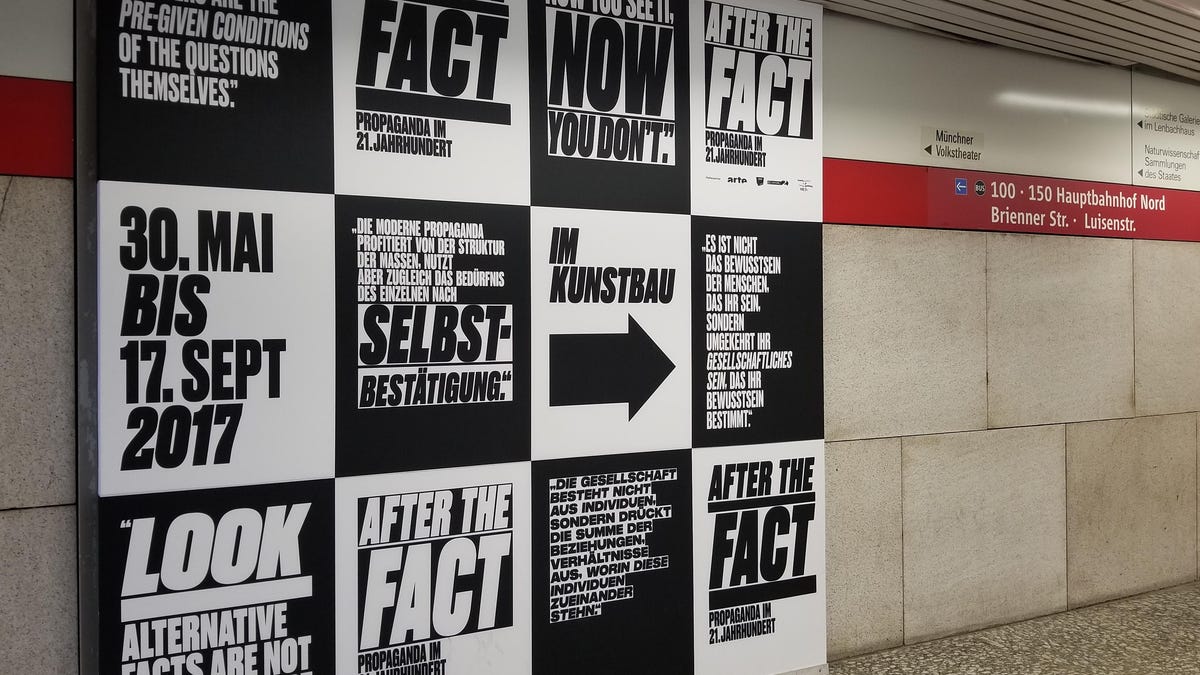

An exhibit at Munich's Lenbachhaus-Kunstbau Museum shows how the propaganda of today isn't necessarily what we picture.

German Chancellor Angela Merkel stands amid several young women dressed in white in a photo that's made the rounds on social media. They're Muslim child brides, a post claims.

"Merkel wünscht den kinderbräuten alles gute," it says in German. "Merkel wishes the child brides all the best."

Except those aren't child brides. And the photo isn't new. It's from April 2016 when Merkel visited a refugee camp in Turkey. She was greeted by young women dressed in their best outfits, not wedding dresses. But try telling that to the thousands of people who shared it online.

That's exactly what Correctiv, First Draft and other groups are attempting to do. These organizations, along with help from tech companies like Google and Facebook , are investigating stories that gain traction in Germany and could impact the country's national election on Sunday. They want to make sure the sort of viral rumors that spread in the US don't happen here.

"There was definitely a lot of misinformation, which had an impact [in the US]," said Jutta Kramm, head of fact checking at Berlin-based Correctiv. "So we said, maybe we should be prepared in Germany."

Fake news has been on everyone's mind since last year's US presidential election. It doesn't help that President Donald Trump uses that phase as his favorite insult for news organizations like The New York Times or CNN. In a year when three of Europe's most influential countries -- UK, France and Germany -- have national elections, it has become increasingly important to ferret out lies before they're widely spread on social media sites.

Photos from April 2016 of German Chancellor Angela Merkel (center) being greeted with flowers in Turkey were circulated online shortly before the 2017 election. People mistakenly said she's surrounded by child brides.

When it comes to Germany, organizations like Correctiv have one advantage: there's not much misinformation about the German election going viral online. Even stories that do gain traction are shared only hundreds or thousands of times, not millions like the lie about the Pope endorsing Trump for president or Hillary Clinton running a child abuse ring out of a Washington, DC, pizzeria. And the long-awaited data dump from hacks of the German Parliament and other German government groups hasn't materialized.

"It has been very ho hum [in Germany]," said Eoghan Sweeney, global training director at First Draft, a nonprofit trying to educate people how to spot fake news.

But that doesn't mean anyone is taking a breather.

All about refugees

Germany, with its strong economy and stable government, has been viewed as the defacto leader of the European Union, particularly with the UK's plans to exit the EU. Angela Merkel is running for her fourth term as German chancellor, and many pundits expect her to beat her opponent, Martin Schulz. Her campaign posters tout, "For a Germany in which we live well and happily."

The reserved 63-year-old, whose nickname is "Mutti" (German for "mother"), is a sharp contrast to Trump, who tends to say whatever he's thinking, particularly through 140-character Tweets. Merkel doesn't even have a Twitter account. Now the German chancellor has been been anointed by some pundits as the new "leader of the free world" -- a position neither she nor her country really relish.

That also has made her a target in misinformation campaigns. Most fake news spread in Germany relates to Merkel's earlier open-door policy for refugees.

A group of refugees hold signs in Munich last year, trying to make Germans feel more comfortable with them following backlash.

When hundreds of thousands of people fled war in Syria and other countries in late 2015, Merkel adopted a strategy to welcome them to Germany. No European country has received as many requests for asylum as Germany, according to the UN. All told, Germany took in more than a million refugees. That fact -- combined with sometimes inaccurate news of violent crimes -- has sparked backlash against Merkel's policy, and it also has caused her and many other Germans to become less open to refugees.

"There is one dominating topic [for misinformation in Germany], and that is everything that is related to refugees, migrants, Muslims and Islam," Correctiv's Kramm said.

Hoaxmap keeps track of the number of rumors about refugees commiting crimes or being granted excessive welfare that have been debunked in the country. Between April 2013 and the middle of September 2017, the total tallied by Hoaxmap was 482.

The rate of new rumors has dropped since 2016, said Karolin Schwarz, one of the creators of the Hoaxmap blog. Instead, there are more conspiracy theories and statistics being taken out of context, she said.

"Right wing populists still use asylum politics and criminal migrants for their campaigns, but things have changed," said Schwarz, who now works for Correctiv. "We have a lot more conspiracy theories, like one about Merkel planning to get 12 million refugees to Germany."

Modern propaganda

As I walk down a long ramp into Munich's Kunstbau Museum, I can see framed newspapers lining a wall. There's actually 151 of them, all from the day after the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorists attacks on the World Trade Center in New York.

I stop by a small TV and put on a headset to listen to Anita Sarkeesian, a feminist media critic and GamerGate target, talk about sexism in video games . Next, I walk by a display of advertisements that encourage Italians to have children as part of last year's "Fertility Day" campaign. One poster, showing an attractive woman holding an hourglass, says (translated from Italian): "Beauty knows no age, fertility does."

Another display shows Trump Mexican wall memes, while another contains a Facebook post from Germany's far-right Alternative für Deutschland party that shows a woman cooking and says, "Do you also see a woman cooking in a kitchen? This is politically incorrect." The post was in response to a proposal by a German minister to prohibit sexist ads.

Lenbachhaus-Kunstbau Museum included a wall of 151 framed newspapers, all from the day after the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center in New York.

I'm at an exhibit called "After The Fact: Propaganda in the 21st Century." It's part of a special program from the Lenbachhaus-Kunstbau Museum about how the propaganda of today isn't necessarily what we picture. Along with the exhibit, the museum organized several free talks spread over three months on topics such as "From Propaganda to Fake News: Deception, Manipulation and Truth in the Contemporary Media Environment."

The exhibit's point: Even though we tend to think of propaganda as a tool of totalitarian regimes like Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia, it's a lot more. The exhibit's curators want to "broaden the definition in light of the societal, political and technological developments of the 21st century." One of those developments is the spread of fake news.

That's true even in Germany, which has some of the strictest hate speech laws of any democratic nation. It's illegal, for instance, to display Nazi symbols or deny that the Holocaust happened. Even during a neo-Nazi march in August in Berlin, people were barred from chanting anti-semitic phrases or carrying Nazi regalia. Instead, the demonstrators stood in complete silence.

In a law going into effect in October, Germany will be able to fine social media companies as much as $57 million if they don't remove or block hate speech from their platforms within 24 hours. While the new regulation has been criticized by digital and human rights groups, Heiko Maas, Germany's federal minister of justice and consumer protection, said the law is meant to "prevent a climate of fear and intimidation" and extend to the digital world the German regulations found in the real world.

Even as hate speech is banned in Germany, fake news and propaganda have found ways to evolve and spread.

Tech and news working together

Silicon Valley has been grappling with the role social media sites played in swaying the US election. Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg , who at first downplayed the impact his company's social network may have had on the spread of false news, has now embraced those concerns and is working to address them globally.

While the fake news scourge is muted in Germany, Facebook still has a presence. The company has discovered and removed tens of thousands of fake accounts here by identifying patterns of activity such as repeated posting of the same content. It also has hosted account security training sessions for members of the German parliament and political parties.

Facebook has placed ads in publications like Süddeutsche Zeitung, Der Spiegel and Stern to give readers tips to spot fake news. And it has partnered with Correctiv, First Draft and others to make people more aware of misinformation.

Campaign posters for German Chancellor Angela Merkel and her opponent, Martin Schulz, dot the side of the road in Berlin. The national election will be held Sunday.

"Protecting authenticity and ensuring a safe and secure environment is an ongoing challenge -- one that requires vigilance and commitment," a Facebook spokesperson said in a statement.

Google, for its part, is focused on three things when it comes to the German election: "promoting accurate content, offering data the provides helpful context and surfacing unheard voices." It too is working with Correctiv and First Draft to monitor misinformation during the German election.

"We strongly believe in the importance of quality journalism and the power of collaboration between tech and media companies to strengthen it," Isa Sonnenfeld, head of Google Germany's News Lab, said in a blog post. "During elections, this is more important than ever."

WahlCheck

"Hallo und herzlich willkommen beiWahlCheck17, dem Newsletter mit dem täglichen Update zu Fake News und Falschinformationen," the message says. "Hello and welcome to WahlCheck17, the newsletter with a daily update on fake news and false information."

WalhCheck17 -- ElectionCheck17, in English -- is a joint effort by Correctiv and First Draft to alert journalists and other subscribers to what misinformation is being shared online.

"Our project is not debunking fake news about Taylor Swift or other celebrities," said Kramm, a former editor at the Berliner Zeitung newspaper. "It's not even looking at science or planet change stuff. It's now focusing on the general election campaign."

When a story is spotted that appears to be false, the WahlCheck17 team conducts an investigation. If it can prove the report is a lie, it will write a post of its own.

Tools the team members use to investigate include Google Trends, Facebook's Signal and Crowdtangle, and Trendolizer to determine what content is being shared. Newswhip lets the investigators predict how widely a piece of content will be shared, while Trendsmap keeps track of Twitter trends by location and Botswatch monitors bot networks. They also use the Fact-Check Tag for Google Search and Google News to increase the visibility of fact-checked information.

Facebook also share articles that have been flagged as "disputed" with Correctiv/WahlCheck 17. If the team determines a report to be false, Facebook will display a post from the investigative team alongside the original post in the new Related Articles feature that became available in Germany in August. It doesn't delete the fake news report, though, even if Correctiv or others prove it to be false. That's because Facebook doesn't want to be the "arbiters of truth ourselves," in the words of Zuckerberg.

Even with the tools, debunking rumors "comes down to basic journalistic fundamentals," First Draft's Sweeney said.

People "say, 'how can we evaluate fake news, what are latest tools?'" he said. "I'm not pulling out a big red contraption that says, 'this is true, this is not.'"

The original plan was for WahlCheck17 to monitor online rumors in the four weeks leading up to the election. Now it will continue for at least one week afterward. And there are efforts to go beyond that. First Draft, for instance, is working on curriculum for media outlets to teach them skills and tools to evaluate what they're seeing online.

The teams are too small to evaluate everything, and there's a constant worry that they may be too late. But they also relish their successes when they can debunk something -- like the supposed Merkel-child brides photo.

"Sharing and posting stuff is a very easy thing to do," Kramm said. But "people must learn to be a bit more responsible and know about what happens if they spread fake news."

iHate: CNET looks at how intolerance is taking over the internet.

Life, Disrupted: In Europe, millions of refugees are still searching for a safe place to settle. Tech should be part of the solution. But is it?