Flying a simulated Apache helicopter

At the Lockheed Martin Simulation, Training and Support facility, I spent a couple hours testing some of the military's latest digital training equipment.

ORLANDO, Fla.--I'm sitting at the controls of an F-35 Lightning II and my missiles are locked in on a couple of nearby enemy fighters.

I fire twice, and off shoot a couple of missiles, screaming toward their target. Victory is mine. As long as I don't lose control of my own fighter and go plummeting into the ground.

I grip the controls and struggle back toward the aircraft carrier I launched from. The voice in my left ear becomes a little alarmed as I approach the landing strip and just about as I'm about to cartwheel into the sea, I manage to land.

Despite vanquishing my foes, the militaries of the world are probably lucky that I won't be fouling their skies anytime soon.

And of course, no one actually let me get behind the rudder of any eight-figure planes. Rather, I spent part of my Thursday at Lockheed Martin's Simulation, Training and Support facility here, getting a look at some of the latest military training equipment being employed today.

This was my latest stop on Road Trip 2008, during which I'm driving around the South writing stories on some of the region's most interesting destinations, attractions and technology.

As it happens, Orlando is home to some of the world's leading simulation technology, and that's largely due to the fact that the U.S. military has a huge training presence here. And that's why Lockheed Martin's predecessor, Martin Marietta, set up shop here in the 1960s.

Today, Lockheed's Orlando simulation facility is a giant campus with some of the widest hallways I've ever seen. And because it is playing host to training technology that is intended to help soldiers heading off to Iraq perform better, it has seen nearly 100,000 military personnel come through and partake of its simulation facilities.

Because this Lockheed outpost contracts its services to both the U.S. and some foreign governments, as well as other "customers," and performs more then 300 simulation systems demonstrations a year, it employs three dedicated systems engineers, as well as 52 strategic product engineers and 20 others who help out in various capacities, according to senior systems engineer Joe Freeman.

One of the first things Freeman showed me was an array of three connected computer monitors attached to a simulation system known as the Combat Leadership Environment (CLE). This, he explained, is used to put soldiers into the middle of daily missions and helps commanders teach them how to move through those missions while encountering unexpected difficulties.

"We try to stress them out," Freeman said. "If they're doing well," we can make the situations harder.

The idea, essentially, is to train soldiers to think on their feet and to follow proper standard operating procedure, even when confronted with scary or stressful conditions.

"As he goes through," Freeman said, speaking of a soldier, "they throw curveballs at him. As he drives around (in the simulated city) they can throw things at him, like mortar (attacks). That kind of adds to the stress level....We're not trying to teach them what to think. We're trying to teach them how to think."

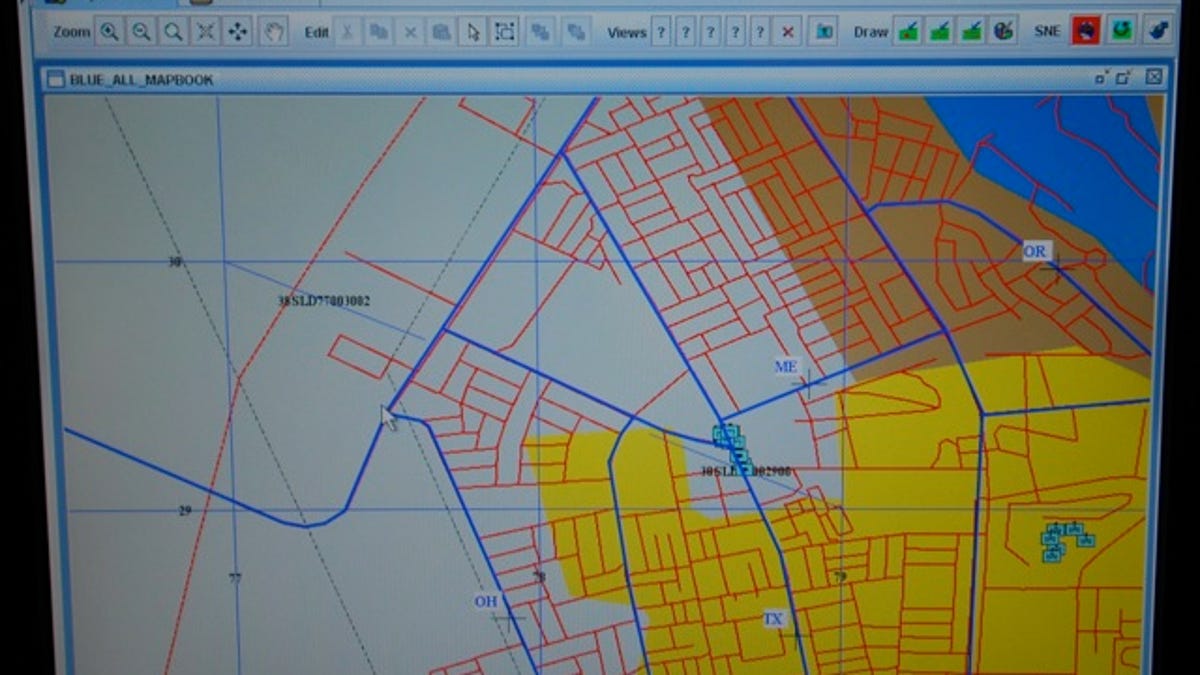

Next, Freeman demonstrated GUSS, the generic unmanned supervisory segment, which puts military personnel in the position of controlling unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), the drones that fly over war zones, attacking under the direction of someone behind a computer far away.

Using what's known as a situational awareness view, a soldier can control as many UAVs as they can comfortably monitor. And the system allows the UAV's director to see both the vehicle's planned flight path, as well as what's in its visual path.

Next up, I was ushered into the seat of a simulated Apache helicopter cockpit. I thought someone would show me how it works, but instead, I was told to "fly" the helicopter around a digital Baghdad, searching for enemy trucks to shoot.

Given my past performance at various flight simulators, I was sure that the very first thing that would happen would be that I would crash the Apache.

Instead, under Freeman's patient tutelage, I managed to keep the helicopter afloat for a while. He instructed me on using a pair of foot pedals to keep the aircraft from spinning out of control and in using a pair of joysticks to maintain a steady altitude and speed.

I seemed to be doing OK, with Freeman praising my flying, until he told me try to land it. Disaster.

As I got closer to the ground, as displayed on the computer screens in front of me, the Apache accelerated, and terra firma seemed to be approaching faster and faster. As Freeman exhorted me to recover, I crashed. Not good.

No matter. Except for the little problem with landing, Freeman said I had done well. My head swelled, and I think I'm ready to fly Apache missions now. Or perhaps not.

Then, it was on to the F-35 Lightning II. More of the same. I did well enough to earn a few compliments from the kind folks who held my hand through the simulation.

Another system Freeman showed me was the so-called Deployable Virtual Training Environment.

This, explained Freeman, is a system built from off-the-shelf computer components that is designed to give Marines a way to work on their combat skills while not in the field. It works by putting them through the paces of various battle scenarios involving any combination of friendly and enemy vehicles, weapons systems, and aircraft.

The last simulator I was shown was the Virtual Combat Convoy Trainer, a faux-Hummer housed in a room surrounded almost entirely by big screens on which is projected a digital representation of an on-the-ground scenario in Iraq.

I was curious about this, but then I was instructed to climb into the Hummer and to grab a real M-4 rifle. I was told to lean out the window and shoot the rifle at Iraqis that appeared on the screen. This was a very strange instruction for me to follow, given my feelings about war and guns, but I decided to pretend I was in a video game.

After all, that is pretty much what this was: a video game that just happens to have a slightly more meaningful purpose than, say, Call of Duty 4.

After a couple of minutes, I was told to climb into the turret of the Hummer and to fire away with the machine gun on top. It took me a minute to get the hang of that, but pretty soon I was blasting away at a series of enemy soldiers on-screen, mowing them down with ease. This was a very strange situation.

Even stranger, perhaps, was when one of the Lockheed Martin staffers climbed up on top with me and told me to pose in one of those iconic photos where soldiers grin and brandish their weapons. I put on my best smile and looked at the camera.

Before I left the Lockheed Martin facility, program manager and senior training systems analyst Steven Tourville came in and talked about what he said really differentiates the company from its competitors: an emphasis not just on giving soldiers the best technology, but on what he called Human Performance Engineering.

This is the philosophy that, since soldiers have been given more and more complex weapons, vehicular, and other systems to work with while in combat situations, they have a harder and harder time mastering them and therefore, are becoming more and more overwhelmed when in the field.

As a result, Lockheed Martin is emphasizing repeated practice in simulation environments with plenty of accompanying feedback. And that, Tourville said, has traditionally been the missing link.

"We acknowledge that technologies are great for training, but they may not always be the answer," Tourville said. "We're trying to improve the performance of the human."

As Road Trip 2008 continues, please be sure to follow my progress on this blog, as well as on Twitter and on my Qik channel.