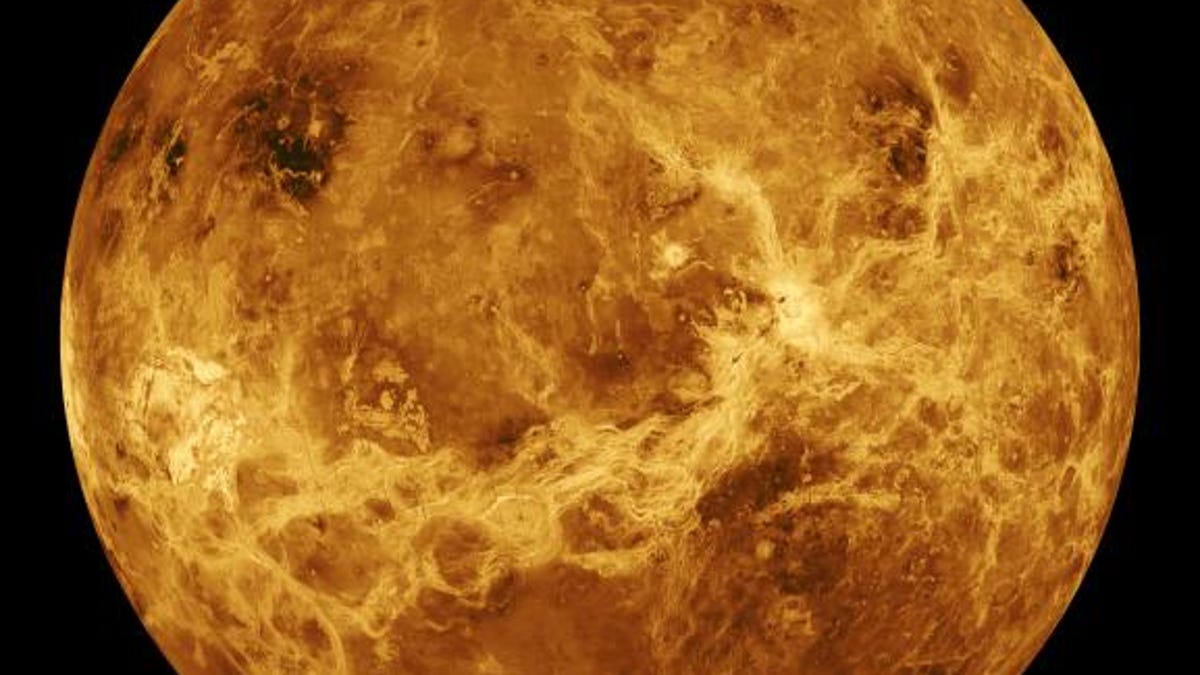

Failed Soviet Venus lander to crash-land on Earth instead

It's been 45 years since the Soviet Union tried to send the probe to the surface of Venus. The spacecraft's return could be too close for comfort.

Kosmos-482 was bound for the surface of Venus.

Soviet spacecraft Kosmos 482 was designed to survive the crushing atmosphere of Venus, but failed to escape the pull of Earth's gravity after launch in 1972. Pieces of the vehicle burned up while reentering our own planet's atmosphere a little later, but at least one big hunk appears to still be orbiting above us and may crash to Earth in the coming months.

One amateur skywatcher who has been monitoring the intriguing bit of space junk told Space.com he guessed it could come down as early as later this year. But other experts estimate it has at least another year or two before it reenters the atmosphere and likely makes a big splash somewhere.

Among the least concerned is the European Space Agency's space debris office, which told me the Soviet space scrap "is currently on a 203 km x 2402 km (126 x 1493 miles) orbit. Our predictions -- and they agree well with independent assessments -- don't see a reentry before the mid 2020s."

Another veteran satellite watcher, Marco Langbroek, plugged data for the Kosmos 482 Venusian lander into a model used by a number of NASA missions.

"Assuming the hardware still on-orbit is the semi-globular reentry vehicle, the model suggests it might survive until early 2020," he said.

However, Langbroek and everyone else I contacted for this story caution that predicting exactly when the failed craft will come back home is difficult because there's no way to know what part of it still remains. Its highly oblong orbit also makes modeling tough.

"We don't know a lot about (the remaining pieces of Kosmos 482), like their shape and rotation, which makes it difficult to get an accurate prediction on reentry," John Crassidis, a space debris expert at the University at Buffalo-SUNY told me. "Solar activity is an issue as well."

What makes Kosmos 482 a little different from your average piece of space garbage, though, is that it's particularly tough. If the chunk still in orbit is indeed part of the lander, it was designed to withstand pressures equivalent to the deep ocean and heat up to 467 degrees Celsius (872 F).

"If it *is* the entry sphere, it might well survive Earth atmosphere entry and hit the ground. In which case I expect it'll have the usual one-in-about-10,000 chance of hitting someone," writes Harvard astrophysicist Jonathan McDowell on his space report. "The vehicle is dense but inert and has no nuclear materials. No need for major concern."

McDowell agrees with ESA that Kosmos 482 could keep on orbiting for another five years or so, which means it might reach half a century in orbit since failing to come anywhere near its target.

Whenever the lander finally does make an uncontrolled landing on Earth instead, it's likely to generate some buzz when its orbit starts to decay towards inevitable reentry. The vast majority of space debris that makes it all the way back to the surface of Earth falls in the ocean, just as China's Tiangong-1 did last year.

But if the very remote chance that Kosmos 482 could hit a populated area does come true, it's liable to land with a bigger thump than the little fleck of space debris that tapped an Oklahoma woman on a shoulder in 1997.