When in Roma

Science is all well and good, but getting pregnant might take some magic.

This is part of CNET's Technically Literate series, which presents original works of short fiction with unique perspectives on technology.

Dorte DeSwaart was the best scientist I ever hired: intelligent, inventive, industrious, disciplined and persistent. A 6-foot-tall beauty from Amsterdam, she had only been at Lamark Technology a year before she discovered the link to an important tumor-suppressive pathway that was going to win us a Nobel, at least. Aside from being our brightest hope, Dorte was also nice, just plain nice. I'd rush into the lab after catching a late shuttle from Palo Alto, sleepless after a long night spent wrestling with my 2-year-old's tantrums, my 6-year-old's insomnia, my 10-year-old's nightmares and the 6-month-old's asthma, my hair uncombed, boots untied, jacket splattered with baby spit, and there Dorte would be, handing me a cup of the hot cocoa she made herself, dabbing my jacket clean with spot remover, replacing the pot of dead ivy on my desk with the fresh roses she brought in from her own garden. Dorte was everything I longed to be: a calm, generous, sweet-tempered woman with a happy family, a successful career and a brilliant future. "How does she do it?" I thought, splashing cold water on my face in the lavatory mirror after one particularly frazzled morning.

"It's easy for her," a harsh voice behind me said. "Her work is going well, she's about to make an important breakthrough, she isn't going through a divorce, and she doesn't have four children."

I looked up, startled. The only other person in the room was a small woman in a cafeteria worker's uniform.

"I didn't know I was talking out loud," I apologized. I waited. Had I been talking out loud? And even if I had -- how had she known whom I was talking about? And how did she know so much about me? I turned to face her. A spy? The work we were doing at Lamark -- Dorte's work with dysfunctional cilia especially -- was delicate and needed to be kept secret. "Who are you?" I demanded.

The woman ignored me. "She'd give anything to have what you have," she said and turned to go. I was left with an impression of two gray eyes, heavily fringed with lashes, mocking me beneath a black baseball cap.

For the rest of the morning I thought about what I had heard, wondering if I had actually heard it. It was as if that odd little woman was excusing me, somehow, for failing to be as perfect as my research assistant, while in the next breath suggesting that Dorte, about to make "an important breakthrough," envied me. Envied me for what? My job? Ever since my recent promotion to senior director of the Oncology Department I had been under pressure; the job involved far too much administrative work, which I am not good at, and not enough time in the lab, which I love and used to -- but who knew anymore -- be good at. She wouldn't want my job and she surely would not want my divorce. Dorte's husband, Fred, was a gentle giant of a guy and their marriage, at least on the outside, looked solid. My marriage to Talc had always been shaky, nothing new there; we had survived the shutdowns of two of his startups and only his affair -- if that's what it was -- with one of his investors had kicked us over the edge. As for the children -- did Dorte really want four children? My god. A faulty condom, a missed pill, a defective IUD and, with the last, a drunken night of make-up sex with a sobbing husband in a gated, heavily guarded and hideous resort in Santo Domingo. Anyone could have four children under those circumstances. But maybe Dorte couldn't? I had heard her say she and Fred wanted children, lots of children, and that they hoped to have more soon.

They already had one. Lisbet was 3, one of those impossibly beautiful little girls who don't look quite real. Dorte and Fred were both big-boned people with rosy cheeks, and though they'd left the Netherlands long ago they still looked slightly foreign in their handmade sweaters and clogs worn with socks. Dorte sometimes actually came to work in braids, and Fred, a medical technician at Stanford, wasn't embarrassed to be seen off duty at Peet's in tie-dye. But Lisbet was tiny, elfin, with a dandelion explosion of red curls, a porcelain complexion and a highly developed sense of style, pointing out Stella McCartney and Zulily designs on the laptop which her parents eagerly ordered. They adored her. Photos of Lisbet covered every free surface of Dorte's workstation and she phoned or Skyped or texted emojis to the child at least three times a day. On Friday afternoons she took Lisbet out of day care and brought her to work; we gave her a toy microscope to play with and she busied herself for hours drawing pictures of cells. She wanted to be a "science mama," too, she said, when she grew up.

One Friday, about a week after my encounter with the odd little cafeteria worker, Dorte brought Lisbet in as usual, but Lisbet was unusually whiny and restless and she soon tired of her coloring and her microscope and begged for gelato. When Dorte asked, I nodded yes, of course, they could leave and go get something to eat. Coming out of a meeting later that day, I was surprised to see them both still sitting in the cafeteria. Dorte's breaks rarely lasted more than 10 minutes but here she was, at a corner table with, I was shocked to see, the same old witch in the baseball cap, who, hands waving, eyes flashing, seemed to be spinning some sort of fantasy which had Lisbet entranced, her gelato untouched. Dorte met my glance with a roll of her eyes. She had no use for storytelling, I knew that, because I had tried to give Lisbet a fairy tale book last Christmas at the DeSwaart's annual cookie party and Dorte, politely, firmly, had placed it high on the mantle. "Don't you read to her at bedtime?" I had asked, surprised, and Fred, taking my elbow and leading me to the table laden with hand-painted plates piled high with fragrant stroopwafels and boterkoeks and Janhagels, had said, "Yes. We read to her at night. But from 'Origin of the Species.'" I thought he was kidding, and laughed, but of course he was not; neither he nor Dorte made jokes and they never said anything that was not factual.

"What was that all about?" I asked Dorte when she brought Lisbet back to the lab for her backpack and jacket.

"Just a story," Dorte answered.

"About an egg," Lisbet said, excited. "This girl threw an eggshell into the ocean and it turned into a boat and she sailed away and was safe..."

"A story," Dorte repeated, patient. "Your friend came up and started talking to us..."

"My friend?"

"She said she knew you."

"No way," I began, but Lisbet interrupted.

"Can we come back for another story next week, Mama?"

Dorte smiled. "Of course meissie. If you want to."

But Lisbet didn't come back the next week. I don't know exactly how it happened; my own week was taken up with administrative meetings, organizing the upcoming international conference in Rome, fights with Talc and endless schedulings and reschedulings of soccer practices, swim practices, day care cancellations, PTA meetings, doctor appointments, lawyer appointments and physical therapy sessions with the baby; I did try to emulate Dorte and say "If you want to" to my family and assistants once or twice and I did of course notice that Dorte was absent from work but I didn't get the whole story until Fred emailed to tell me that Lisbet had died.

How? Dorte volunteered nothing but I had found in working with her that if I asked direct questions she would answer directly and that is how, over the next few months, I slowly found out the details. It seemed that after they went home that Friday night Lisbet developed several large open sores on her lips and inside her mouth. Their pediatrician told them this was not uncommon. He said that her fever would break soon and the sores would clear up by themselves. He advised them not to take Lisbet to the hospital. Lisbet wasn't in any pain, though she looked like she should be; she was sweet and quiet as ever, singing that depressing song from "Frozen" -- the same song the baby liked so much -- and drawing eggshell boats. She was completely recovered by Tuesday but then, overnight, bam, open sores again. Dorte and Fred panicked, overruled their pediatrician, and took her straight to Emergency. That was Wednesday. By Thursday Lisbet was dead. She had picked up a renegade staph infection in the hospital which had torpedoed straight through her tiny body -- those open sores were an open invitation for infection and none of the doctors could save her.

A lot of couples can't survive that sort of tragedy. Talc and I, who couldn't survive even an evening together at that point, would have been destroyed if anything happened to any of our children, but Fred and Dorte never blamed each other -- or the doctors -- or the hospital. They just grieved. It was hard to watch. They didn't have a funeral -- they were agnostics -- and after a week, Dorte came back to work. She walked around as if she was made of broken glass, but she monitored her zebrafish with her usual attentiveness and she was as calm and caring as ever, the one who took your eyeglasses off and cleaned them with a soft cloth, the one who brought you hot tea and spiced cocoa, who asked about you and did not speak about herself. The kids and I would see her and Fred silently riding their bikes through the Stanford campus or out at Crystal Springs on the weekends, cheeks flushed, legs steadily pumping, and they always greeted us with a friendly wave, but the evenings of Indonesian takeout and pingpong in their cottage stopped and we were not surprised when they politely refused to accept the season tickets to Montalvo that Talc and I did not have the heart to go to together.

No one saw them socially until Dorte, to my relief, hosted her cookie party months later on December 5th. Coming in with the children, the baby in my arms, I was shocked to see Lisbet's trike still on the front porch, her water wings still on a patio chair by the pool and her big wicker chest of dolls and stuffed animals still open in the living room. My three oldest filled their plates and went into the game room immediately to watch videos, but the baby wanted the toy box and I saw it was safe to set Happy down beside it, for the glass coffee table, its edges still padded with bumper strips, was cleared of books, vases and knickknacks, and when I carried my gift bottle of brandy into the kitchen I saw sippy cups and a Peter Rabbit china set in the cupboard and Cheerio boxes and juice pouches stacked on the pantry shelves.

"It's like they can't move on," I said to our marriage counselor, when I told her about it the next day.

"Really?" she said. "It sounds to me like they are moving on. They're probably saving these things in hopes of having another child soon."

"Maybe." I was hesitant. "They're already in their 40s."

"That's not too late," the marriage counselor chided. "The important thing is to keep on trying." She looked first at Talc, then at me. "Don't you agree?"

We did. Talc and I had been "trying" as best we could and around the beginning of that next year he finally moved back in. It wasn't easy for us to be together -- his irritating little he-he of a laugh, my careless cracks -- and we weren't patient people, like the DeSwaarts, but at least his girlfriend had gone back to Korea, I had stopped my raging jags, and the children had calmed down. When it came to the kids, we both agreed on one thing: They came first -- and agreeing on that helped us agree on other things.

We had been lucky with our children. They were a rowdy group, high-strung and highly accomplished. Our oldest, Harry, had just scored 2,349 on his sixth grade SAT; Hilary captained her soccer team, swim team and gymnastics team; Hannah played a flawless violin solo at a recent New Mozart recital; and Happy -- well, we just wanted Happy to live up to his name, and so far he had. I tried -- and failed -- not to brag about them, and I also tried, and failed, to ignore Dorte's hungry looks at the Facebook photos I used as screensavers. Now that I understood she and Fred were trying to get pregnant I saw all the signs -- the way Dorte bolted from the lab at odd hours to meet Fred at home, her uncharacteristically dainty walk down the corridors when she returned, her countless doctor appointments, her pallor and the dark circles under her eyes. Despite her obvious exhaustion, her work had never been better. Her recent discovery of a previously unknown function of the p53 gene had us all excited. But Dorte, always conscientious, refused to reveal any of her findings until she was sure they were correct. I nagged but it got me nowhere. Despite pointing out that her discoveries could, once published, not only win us every major prize in the world but lead to the actual cure of pancreatic cancer, Dorte could not be pushed.

One evening when we were both working late, I brought my tea over and sat down beside her in the cafeteria. Scientists are night owls and neither of us was tired, though we agreed we would not mind owning a few helpful robots -- I wanted one to dictate letters and departmental memos and Dorte said she'd like one to help Fred in the garden. "So much of what is coming out in technology today still seems like magic to me," I admitted.

"Magic?" Dorte shook her head. "There is no such thing as 'magic.' Only common sense, applied sensibly."

"Galileo was an astronomer who believed in astrology," I reminded her. "Newton was an alchemist who spent his life trying to turn lead into gold."

Dorte wagged her finger at me, unsmiling. "You're teasing," she said.

"What about all these new," I ventured, "inventions at the fertility clinics? Have you and Fred had any..." I almost said luck, but stopped myself, "positive results yet?"

"No," Dorte admitted, dropping her eyes. "We have not tried everything yet of course, but we have tried clomiphene, metformin, ICSI, IUI, so many IVFs..." her voice trailed off. "Six IVFs. None of them took. It surprises me," she said, frankly. "Before I met Fred I was pregnant all the time."

"Miscarriages?" I asked.

She gave me a puzzled look and I looked away. Who knows why I never even considered abortion for myself. Surely I should have when the amnio results came back on Happy. But I hadn't. Talc hadn't. On that, we'd been united. Or crazy. Or arrogant. Thinking we were super powers who could handle the special demands of a Down Syndrome baby and still be good to each other and to our other children.

"I'm sorry," I said. "Maybe, next week, at the International Conference? Why don't you bring Fred to Italy this year? Sometimes just getting away helps. And Rome is so..."

"Rome?

The harsh voice was familiar and we both looked up. Before we could say anything, the cafeteria crone, whom I had not seen in months, pulled out a chair and sat down. She had a feral smell that despite myself I half liked. But she paid no attention to me. Her gray eyes were on Dorte.

"I have a friend in Rome who can help you," she said.

"A fertility doctor?" Dorte asked politely.

"A Roma."

Dorte looked at me.

"Gypsy," I explained, and raised my eyebrows. Dorte was the last person in the world to go to a fortune teller.

"Miracle worker," the woman corrected me.

"Dorte and Fred don't believe in miracles," I said, smiling, but Dorte, reminding me I had a meeting, blew me a kiss, waved me away and turned toward the old woman. My cell buzzed; I had to get back; I left them there.

I love Rome; Talc and I honeymooned there, years ago, but I was almost glad he decided to stay home with the children this time; I was overwhelmed with the thousand niggling tasks needed to make the conference run smoothly and for the first two days I scarcely left the hotel. On the last afternoon I finished my duties early and escaped from the stuffy conference rooms without being noticed; I had a few hours to wander through the Jewish Quarter, buy a few presents, peer over the bridge into the Tiber, and just sit with an espresso at a cafe in Trastevere before I had to get back.

It was while I was returning through the piazza by the ancient church of Santa Maria that I saw a blonde head, crowned with braids, gliding high above a crowd of Japanese tourists. "Dorte!" I called. I hadn't seen either her or Fred since we'd arrived; hoping they'd been holed up in their room making a baby, I hadn't even resented Dorte's last-minute decision not to present her findings on the p53 gene. Calling her name again, I pushed through the crowd but she was no longer by the fountain where I thought I had seen her. Turning, I saw her climbing the church steps with a young girl. The girl could not have been more than 14, a slim teen with tangled black hair, and, when she turned to glance behind her, I saw she had a silver ring in her nose and the same astonishing light gray eyes I had seen on the cafeteria worker. A beggar? Dorte was notoriously generous; I had seen her give 10, even 20 dollar bills to the homeless asking for handouts at the Sunday farmer's market. But Rome wasn't safe like Palo Alto. Remembering reading in my guide book that "any able-bodied beggar is probably a robber," I decided to follow them.

It was dark inside the church after the glare of the piazza and it took a second for my eyes to adjust. Except for a few scarfed women kneeling in front, the church was empty. Puzzled, my eyes passed over the domed golden ceiling with its rich mosaic figures to scan again the vacant pews. No one. I shrugged. Dorte in a church? Not likely. She must have slipped out a side exit the minute she saw where she had been taken. For some reason, however, I lingered. I found myself standing by the door and though all I did was stand there, I felt something bubble up, not a prayer exactly, but an exhalation, a little breath of gratitude. I had so much. I closed my eyes. Thinking of my children's faces, Talc's tentative smile, the work I was permitted to do in the field that I loved, Thank you, I said. Thank you.

The farewell dinner that night was lavish, 20 courses at a restaurant by the river, and in between the artichokes and the lobsters and the pastas and salads and the toasts and bad jokes and grandiose plans for the next conference, I glanced across the table to Dorte and Fred. They were sitting shoulder to shoulder, eating everything on their plates, chatting with their neighbors. I was not surprised to see that Dorte was the first to notice that the elderly doctor from Hungary was choking and to perform a swift efficient Heimlich that saved his life, nor was I surprised to see her take the elbow of a young clinician from Detroit who had had too much wine and help her off our bus and back into our hotel. There was no chance to talk to her alone that evening or on the flight back to SFO and it wasn't until a few weeks later that I was able to again sit beside her in the cafeteria with my tea. "So," I said, joking, "did you see the Roma?"

"Yes."

"You did?"

"Yes."

"And did she," I chuckled, "work 'miracles'?"

"Yes."

"You're pregnant?"

"Yes."

"How?"

"The usual way," Dorte said drily.

"No. I mean -- a spell, an amulet, a..." I paused. "What exactly did she ask you and Fred to do?"

"We ate the grass off Lisbet's grave."

I was silent.

"We sucked the raw meat out of seven snake eggs."

"Dorte."

"It worked," Dorte said, her voice fierce, and pushing back her chair she stood up and left me.

That night, in bed, I told the story to Talc. He asked a question that had not occurred to me. A businessman's question. "What did it cost?" he asked.

"Cost?"

"What kind of deal did they strike?"

"I don't know. They must have given her a lot of money. Or maybe," I joked, "Dorte traded her soul."

"Soul," Talc repeated. His voice was flat. But the way he said it sounded a lot to me like "Seoul." The next morning I went downstairs while he was still asleep and went over the leather upholstery of his car with a piece of scotch tape. Sure enough. A single hair, long and black, caught in the driver's seat headrest. His "investor." His rich, young, beautiful "investor." Back from Korea. He had probably been with Jin-Joo the entire time I was in Rome.

The kids and I moved back to my mother's. It wasn't great. It took me two extra hours to get to work in the mornings, Harry's grades went down, Hilary's teams lost every game, Heather threw her violin against a wall and broke it, and even Happy, sensing what was going on, lost his appetite and had to be coaxed to eat. Dorte no longer met me at the door to the lab when I stumbled in, red-eyed, and, as her belly grew, her experiments became uncharacteristically sloppy; she seemed to have lost interest in even her beloved zebrafish. One morning as I drove in I heard a news flash on the radio -- Italian scientists had discovered a property of the p53 gene that could cure pancreatic cancer.

I confronted her in the lavatory. "You gave that gypsy girl all your research findings," I said. Dorte didn't answer. "You traded us in for a baby." I waited. "Didn't you?"

"Yes."

"You're fired."

She left without protest that day but seeing her empty work station and looking at the great mess of memos and emails and requests clogging my computer screen gave me an idea. I went to the head of Lamark Technology and asked to be demoted. I was given Dorte's job which, thanks to Talc's alimony, I could afford to take. I have loved it ever since. I have always been happiest with a pipette in my mouth. I am a good solid hardworking research scientist. I have always believed that just because a phenomena can be explained one way doesn't mean it can't be explained in another. The world is still a mystery to those of us trying to understand it. As for Dorte's defection? For some reason it hasn't bothered me as much as it should. I am glad that her findings made it out to the public, and that people all over the world are standing a better chance of being cured now as a result, and if that isn't "magic" I don't know what is.

After I heard that Dorte and Fred had had a son, sold their cottage, and moved to Italy, I did do a little reading on the Roma, not much. According to one legend, they are strays on Earth because they refused to shelter the Virgin and her child in their flight to Egypt. According to another legend, they are capable of sending souls safely to Paradise on eggshell boats. I hoped that was the story the cafeteria crone had told Lisbet, perhaps to comfort her, and I would have asked the old woman, but I never saw her again.

I didn't see Dorte again either, not for years. Then one Sunday, buying produce at the farmers' market downtown, I felt Happy tug my hand. He was 12 then, not quite 5 feet tall, droll and dimpled, with a 5,000 word vocabulary and a good sense of humor. He led me to an open trailer selling bakery goods -- the same array of stroopwafels and boterkoeks and Janhagels that I remembered fondly from the December cookie parties. Looking up, I saw Dorte carrying a fresh tray to the table.

Her hair had grayed, she had put on a great deal of weight, but her cheeks were still rosy and her hazel eyes were still direct and frank. She pressed my hand warmly and invited Happy and me into her trailer to meet her children. She had four now, she said. We entered gingerly, for the trailer was strewn with toys and pieces of clothing and felt dark, cramped and dirty. Fred, bald and gaunt, rose from the shabby couch where he had been watching television and proudly introduced us to their oldest, a handsome 10-year-old boy who, for no reason, pinched Happy, trying to make him cry (Happy doesn't cry) and to the two tall blonde cross-eyed sisters wrestling on the floor. He offered to let me hold the 3-month-old baby, which I did, for a minute, before handing it back.

"He has teeth," Happy blurted.

"I know," I whispered back.

We both shivered, took the plate of cookies Dorte pressed on us, and left. Back in the car, I buckled Happy in, kissed his sweet cheeks, threw all the cookies out the window and drove away. Thank you, I said as I drove. Thank you.

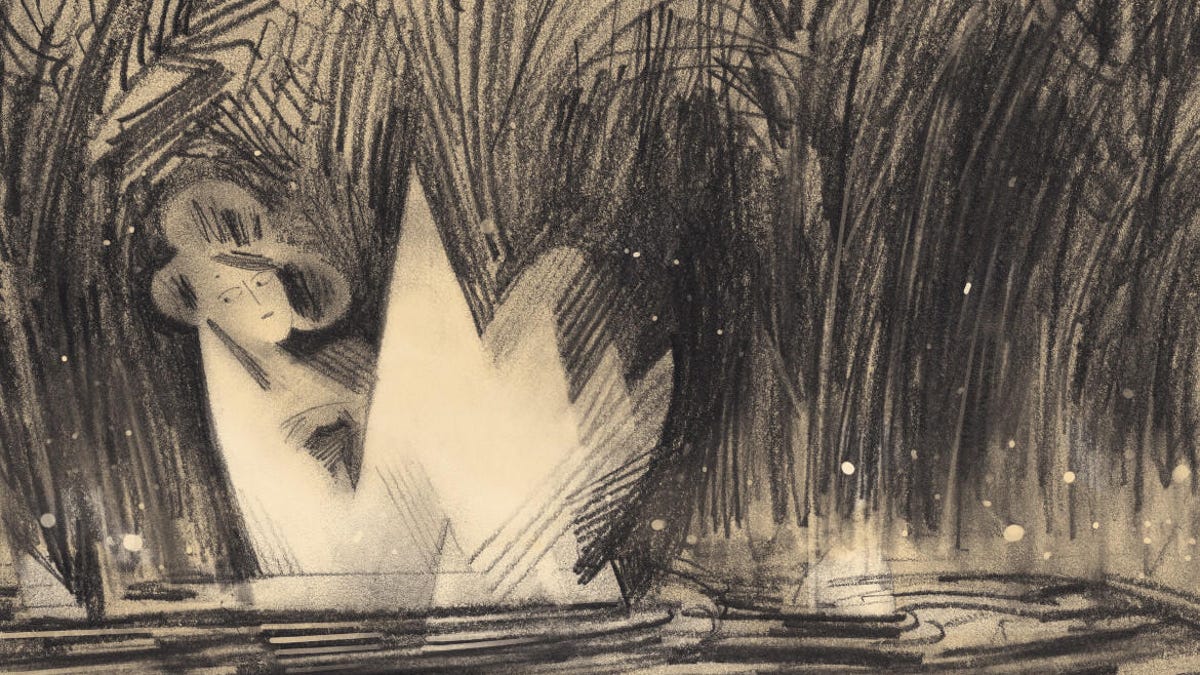

Illustrations by Roman Muradov

Technically Literate: Original works of short fiction with unique perspectives on tech, exclusively on CNET.

CNET Magazine: Check out a sampling of the stories you'll find in CNET's newsstand edition.