Carbon nanotube pencil points to hazardous gases

MIT boffins create a new type of pencil lead that can draw hazardous-gas-detecting sensors on paper. Just don't bring it to the SAT.

Gather 'round kiddies, and I'll tell you a story about pointy wooden things called pencils. Before the explosion of keyboards and touch screens, people used to use them to do something called writing. On paper.

Now, one MIT chemistry postdoctoral student may have given the old-fashioned pencil a new lease -- though not as something you'd bring to the SAT.

Katherine Mirica and colleagues created a novel type of pencil lead, replacing graphite with a highly compressed powder made of commercially available carbon nanotubes. The resulting newfangled lead can inscribe sensors on any paper surface.

So what's the point? The sensors, described in a paper titled "Mechanical Drawing of Gas Sensors on Paper" in the German journal Angewandte Chemie, detect minute amounts of the colorless gas ammonia, an industrial hazard, but could be adapted to detect nearly any type of gas.

The MIT team, for example, is also looking into creating sensors for detecting sulfur compounds, which could prove helpful for sniffing out natural-gas leaks.

"The beauty of this is we can start doing all sorts of chemically specific functionalized materials," MIT chemistry professor Timothy Swager, leader of the research team, said in a statement. "We think we can make sensors for almost anything that's volatile."

Carbon nanotubes -- roughly 50,000 of which add up to the width of an average strand of human hair -- have been shown to be effective sensors for many gases, which bind to the nanotubes and impede electron flow. Creating sensors of this type, however, requires dissolving nanotubes in a solvent such as dichlorobenzene using a process that can be both hazardous and unreliable.

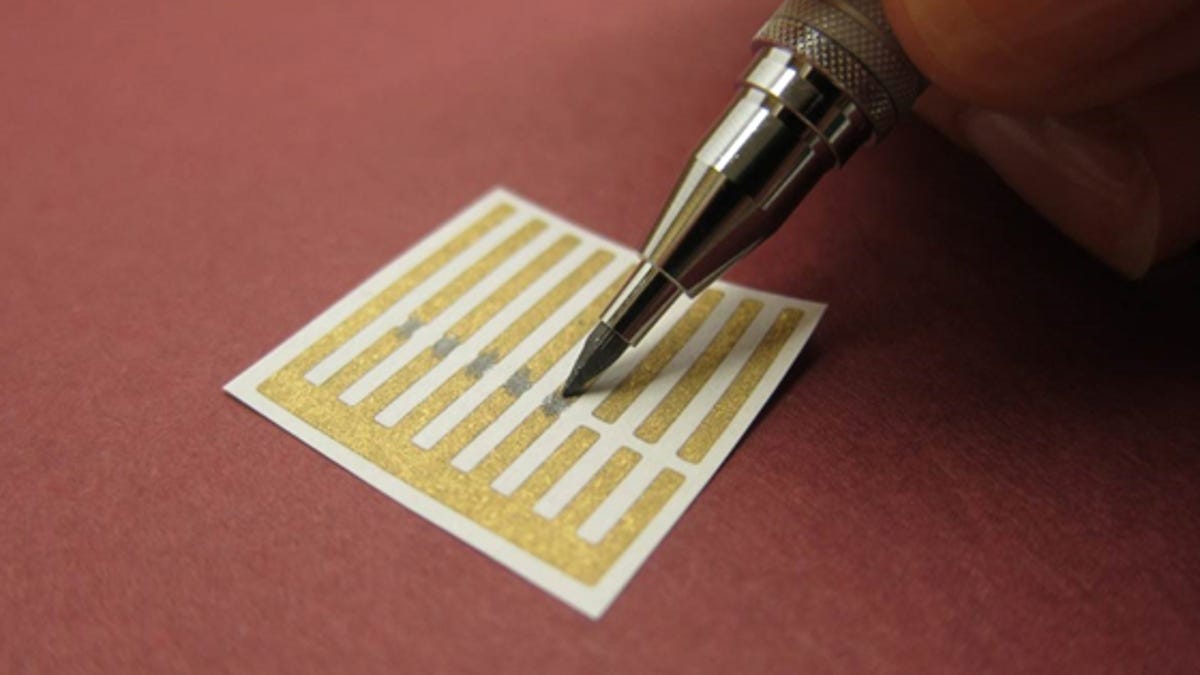

This new fabrication method out of MIT, on the other hand, is among other advantages entirely solvent-free. To create sensors using their pencil, the researchers draw a line of carbon nanotubes on a sheet of paper imprinted with small electrodes made of gold that help measure the electrical current running through the tiny cylinders.

The research was funded by the Army Research Office through MIT's Institute for Soldier Nanotechnologies. This suggests that in addition to high expectations for carbon nanotubes in the medical realm, particularly when it comes to drug delivery and noninvasive blood monitoring, the military also sees great potential for the strong and tiny tubes.