Neuralink's Brain Chip Is Running in a Human. Your Skull Is Safe, for Now

Elon Musk's company shows off a man with quadriplegia playing online chess via brain implant. But it'll be a years before limited trials of a brain-machine interface progress to broader medical use.

Neuralink's Telepathy implant now has been fitted into a human skull, testing whether it can be useful in helping a person with quadriplegia move their limbs again.

Back in January, the Elon Musk-led Neuralink implanted its brain chip, named Telepathy, in a human for the first time. It was an early stage of a six-year study and just one step on a very long path to making the technology safe and useful.

This first device installed is part of a clinical trial Neuralink announced in 2023 testing how well the device works on people with quadriplegia because of a spinal cord injury or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), also known as Lou Gehrig's disease. The idea is to intercept the brain's neural signals to move limbs, then retransmit those signals elsewhere in the body so the patient can control their limbs again.

In an update on March 20, the company streamed live video of its patient, now identified as Noland Arbaugh, playing online chess on a laptop, using the brain chip to move the cursor on the screen.

"Basically, it was like using the Force on the cursor," said Arbaugh, who became a quadriplegic after a diving accident about eight years ago. Arbaugh said he focused on thinking he was moving his paralyzed hand in a certain direction. With some practice, eventually the brain signals he was sending were properly interpreted by the implant and translated into cursor motion on the chessboard.

"I don't want people to think that this is the end of the journey, there's still a lot of work to be done," Arbaugh said, "but it has already changed my life."

Neuralink's journey

Neuralink got approval from the US Food and Drug Administration for the medical test in 2023, but Musk wants to go far beyond that, building what he's called a "generalized input-output device that could interface with every aspect of your brain." In other words, something everybody would use to connect their minds directly to the digital realm.

It's radical sci-fi by the standards of today's computing technology. When Musk first announced Neuralink, he floated the idea of sending messages directly to another person's mind -- "consensual telepathy," as he called it in 2017. His ultimate objective: "a full brain-machine interface where we can achieve a sort of symbiosis with AI," Musk said.

Anil Seth, a University of Sussex professor of cognitive and computational neuroscience, threw a splash of cold water on the news back in January when it was first announced.

In terms of advancing the state of the art, "there's nothing new here, at least not yet," Seth said on X. "Other groups have been developing brain implants for decades and have demonstrated many more impressive results than today's highly preliminary announcement."

He praised Neuralink's installation robot, but also said brain interfaces need more scientific research, not just engineering acumen. "Nobody wants a 'rapid unscheduled disassembly' happening inside their own heads," he said, referring to the tongue-in-cheek term that aerospace engineers use to describe rocket explosions such as the one that destroyed a SpaceX Starship rocket in 2023.

Big barriers to Neuralink's success

Don't expect widespread advances anytime soon. It's easier to get approval for limited medical studies in people whose health problems show no signs of improving than it is to persuade people to implant a nonmedical product inside their bodies. On top of proving the technology and gaining medical approval, there are serious ethical and social barriers to adoption.

Adoption could be held back by Musk himself, a polarizing figure. He became a tech hero to many when he led Tesla to create competitive electric vehicles and SpaceX to build more affordable rockets and satellite-based internet access. But his chaotic takeover of Twitter, now called X, has alienated many who view him as antisemitic or racist.

Another obstacle: people's squeamishness. Telepathy sounds cool, but there's no getting around the fact that a Neuralink implant replaces a piece of your skull, and getting one installed will be a lot more significant than a dentist drilling out a cavity. Neuralink has had problems with infections and implant attachment screws coming loose in tests in monkeys that have drawn criticism from animal rights activists.

"Imagine if Stephen Hawking could communicate faster than a speed typist or auctioneer. That is the goal," Musk said.

Neuralink is working on an app to let people control digital devices, in effect typing with their minds. It has demonstrated the technology with monkeys.

Neuralink is one of many brain implant efforts

The human trial is years late. Neuralink had wanted to begin human tests in 2020.

Meanwhile, rivals are also making progress in the field, called brain-machine interface (BMI) or brain-computer interface (BCI) technology, including an experiment that already has helped a man walk again. In another experiment in 2022, a 250-electrode connection let a mostly woman type at 78 words per minute with her mind after a computer learned how to understand the motor commands she'd use to actually speak -- precisely what Musk was talking about with Hawking, the famed physicist whose physical abilities were largely blocked by ALS.

BlackRock Neurotech has tested implants in humans for years. Paradromics is working on an implant, too. Synchron Medical published test results of a communications implant in 2023. Precision Neuroscience is working on less invasive implants, and Nuro hopes to succeed with noninvasive approaches that require no surgery at all.

Academic researchers have produced a steady stream of research papers too.

What Neuralink is up to

Neuralink is founded on the idea that modern electronics and computing technology can register and interpret the electrical signs of brain cells, called neurons. That computing technology can then communicate back to the body by generating its own signals. The hope is to eventually connect to computers, for example sending signals from a camera to a blind person's visual cortex to enable sight.

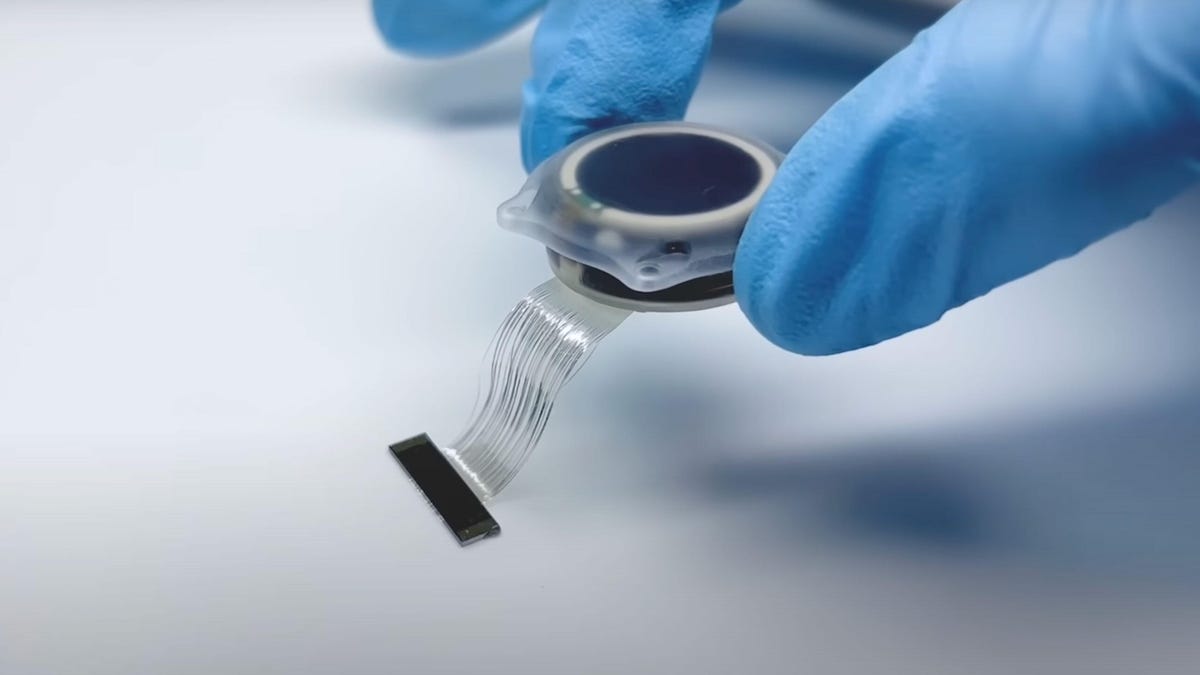

An implant works by inserting 64 threads with a total of 1,024 very small electrodes into the brain. Each electrode can sense the brain's electrical signals. Part of Neuralink's sales pitch is its R1 robot, designed to install these wires without disturbing blood cells in the brain.

The Telepathy unit is roughly coin-size, though much thicker, and fits inside a hole bored in a patient's skull. It carries a processor that oversees the communications with the brain and the outside world. It communicates and charges wirelessly.

The Neuralink human trial should last about six years, according to a brochure about the test.

CNET's Gael Cooper contributed to this report.