Apple's new multitouch patent (FAQ)

Smartphones are the hottest item in tech today, and patent infringement suits are breaking out all over. Here's a look at Apple's newest weapon in the war.

Apple picked up a patent yesterday that could come in very handy in today's thicket of smartphone-related intellectual property litigation.

The patent gets to the heart of what it means to be a smartphone these days: a user interface with a multitouch display. Patent No. 7,966,578 bears the title "Portable multifunction device, method, and graphical user interface for translating displayed content."

But what's it mean? CNET takes a look at some of the issues involved.

First, what does the patent cover?

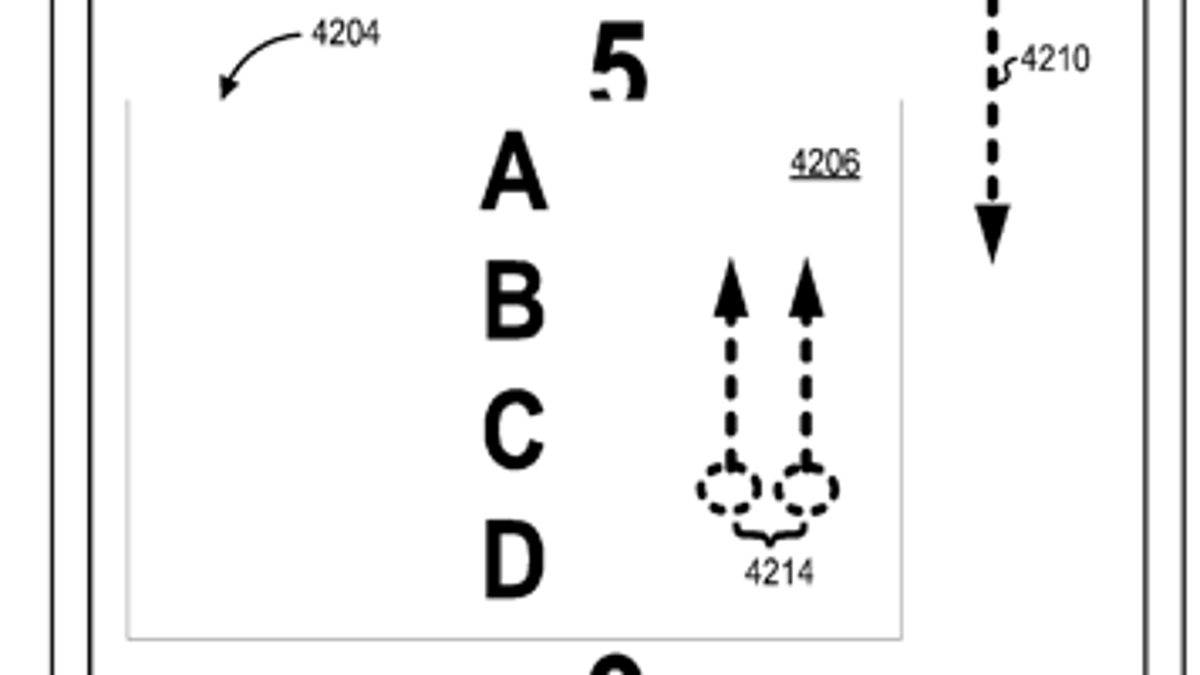

The patent involves some of the most basic things you can do with a smartphone: touch the screen to move elements shown on it. That could be a touch with one finger, two fingers, or more, and the meat of the patent concerns just how many. Specifically, it has a lot to say about whether a sliding gesture moves a whole page of content or just some elements within a frame.

"Depending on the number of fingers used in the gesture, a user may easily translate page content or just translate frame content within the page content," the patent said.

The abstract of the patent reads as follows:

A computer-implemented method, for use in conjunction with a portable multifunction device with a touch screen display, comprises displaying a portion of page content, including a frame displaying a portion of frame content and also including other content of the page, on the touch screen display. An N-finger translation gesture is detected on or near the touch screen display. In response, the page content, including the displayed portion of the frame content and the other content of the page, is translated to display a new portion of page content on the touch screen display. An M-finger translation gesture is detected on or near the touch screen display, where M is a different number than N. In response, the frame content is translated to display a new portion of frame content on the touch screen display, without translating the other content of the page.

Wait, huh? My eyes just glazed over.

OK, let's boil that down a bit. The patent governs how content on the screen moves when you touch the screen. A one-finger touch might move an entire page around, for example, but a two-finger touch might move just content within a particular region that the patent calls a frame. The smaller frame could be any number of things--a scrollable list of items, a portion of of a map.

The patent begins with a claim involving Web pages shown in a stationary window, but other claims specify other tasks: word processing, spreadsheet, e-mail or presentation documents; maps; and scrollable lists of items.

The patent covers this technology on a "portable multifunction device," described broadly enough to include not just smartphones but tablets and potentially other touch-screen devices as well. And just to be clear, the patent's use of the term "translate" means to move something left, right, up, down, or diagonally on the screen, not to convert from one language to another.

Who got the patent?

The inventors are Francisco Ryan Tolmasky, Richard Williamson, Chris Blumenberg, and Patrick Lee Coffman, who applied for the claim in 2007. Apple is the assignee.

All four are on a longer list of inventors awarded Apple's multitouch patent in 2009--although this time around, Apple Chief Executive Steve Jobs isn't on the list.

Why should we care about Apple's patents?

Right now the mobile phone industry is moving about as rapidly as anything in the tech sector--despite the fact that it's festooned with patent infringement lawsuits regarding mobile technology. Those lawsuits have drawn in Apple, Google, Microsoft, Nokia, Motorola, Samsung, HTC, Oracle, and Kodak. Patent infringement lawsuits are very expensive.

Patents, especially broad ones, give these companies a bigger arsenal in such battles. Apple just paid Nokia big bucks in a suit Nokia launched in 2009. Apple's new patent could conceivably be added to existing suits, procedural limits permitting, but patents have a long useful lifespan.

Many times companies avoid litigation by signing patent cross-licensing deals that give each other access to the other's patent portfolio. There, too, patents can be useful: the company with the weaker portfolio typically ends up paying the other in the cross-license deal.

All this amounts to a very high cost of doing business. Incumbent powers with a lot of patents have an advantage over new entrants--think HTC, the Taiwanese company vaulted into the big leagues through Android and that suffered a patent infringement lawsuit from Apple.

Which is why Google is willing to pay $900 million for Nortel Networks' patents and patent applications in a bankruptcy court proceeding.

How big a gun did Apple just get in its arsenal?

A very big one, some believe.

One person worried about its implications is Florian Mueller, who closely monitors the present round of patent suits for his FOSS Patents blog.

"It covers the basic user interface concept of moving touch-screen content with multitouch gestures--not just one particular way to programmatically recognize one particular gesture for this purpose, but any or all ways to do so," Mueller said. "This patent describes the solution at such a high level that it effectively lays an exclusive claim to the problem itself, and any solutions to it."

"Moving objects on a touch screen with multitouch gestures is a very essential function," he added. "I can hardly imagine that smartphones and tablets would be competitive in the future without multitouch object-moving."

So Apple is being a big meanie here?

Not if you ask Apple's shareholders or ambitious executives. Sure, Jobs apparently has a personal ax to grind when it comes to smartphones that adopt ideas that first showed up in the iPhone. But companies exploiting any advantage is hardly a strategy unique to Apple.

Apple products ignited the current round of smartphone innovation, and it would be a surprise to see a company so fiercely competitive and profit-focused suddenly gloss over patents at the heart of its business.

"Since Apple acquired FingerWorks in 2005, they've been regularly filing patents for gestural interfaces. They've had a significant head start on the competition in this regard, and that bodes well for Apple's ability to defend its intellectual property," said Raven Zachary, a former industry analyst who now advises clients on iOS development matters.

Some companies such as Microsoft and IBM enjoy the revenues from patent license deals. Apple, though, shows different behavior, he added.

"Apple seems to only do patent deals as part of gaining access to patents," Zachary said. "If Apple were to defend its gestural patent portfolio broadly in the emerging tablet market, it could really hinder innovation by other technology companies. Does anyone really think that Apple would opt to license its patent portfolio unless it's bilaterally?"

That doesn't bode well for smaller new players such as HTC. Patents grant a monopoly, and withholding technology that's essential for a competitive product could cripple a rival.

What do Apple's competitors think?

They're not saying. Samsung, Microsoft, and Google declined to comment for this article.

But don't expect them to be happy.