Why Apple needs to settle its e-book suits

More and more, it appears that Apple's e-book agreement with publishers was anticompetitive -- or, at the very least, anticonsumer.

commentary Amazon.com has outmaneuvered Apple in the e-books sector. Nowhere was this made more apparent than in court documents released last week.

In antitrust lawsuits filed by the U.S. Department of Justice and others, Apple stands accused of conspiring with five of the six largest U.S. book publishers to raise the price consumers paid for e-books and stifle competition in an attempt to snatch control of the e-book market away from Amazon, the sector's dominant player.

Soon after the Justice Department filed its complaint last month, Apple and two of the five publishers filed motions with a federal district court in New York to dismiss the case.

Last week, those requests were denied by U.S. District Judge Denise Cote. Cote's strongly worded 59-page decision offers several reasons for Apple to rethink its e-book strategy before Amazon pulls away again in the e-book market.

In other words, it's time for Apple to settle. It has so much to lose and very little left to gain by fighting the three complaints, brought by the Justice Department, attorneys general from 29 states, and a group of consumers who are requesting class action status.

This is likely a fight for Apple not worth having. In the complaints, Apple's partnerships with the publishers look in every way anticompetitive and anticonsumer. The case could drag on in the court for years, and even if Apple prevails, the e-book market will undoubtedly have evolved so that any Apple victory is likely to be moot.

Making that scenario more likely is that three of the five accused publishers have already settled: News Corp.'s HarperCollins Publishers, Lagardere SCA's Hachette Book Group, and Simon & Schuster (owned by CBS, which publishes CNET).

As part of the settlements, HarperCollins, Hachette, and Simon & Schuster have agreed to revoke Apple's "most favored nation" status, an agreement whereby each of the publisher defendants guaranteed that prices on hardcover new releases offered at the iBookstore matched the lowest price being offered anywhere else online. The three publishers who settled also agreed to allow e-book merchants to discount prices for at least two years.

That three of the five publisher defendants have settled not only lends credibility to the government's accusations, but it also means that while Apple is slugging it out in court, Amazon can go back to slashing prices, which the merchant has promised to do.

In the meantime, what does Apple have? Like Apple, Pearson's Penguin Group and Verlagsgruppe Georg von Holtzbrinck's Macmillan Publishers have denied wrongdoing and refused to settle. But the combined overall market share of those two companies is about 17 percent.

The last and perhaps best reason Apple should settle is that whether or not the government can make its case against the company, with every new document released in the proceeding, Apple looks more and more like an enemy of book buyers.

A unified front

According to the Justice Department complaint filed last month, Apple was preparing to release the

iPad and iBookstore in the fall of 2009, when executives there approached the publishers with what had to sound like a sweet deal. If the publishers adopted the agency model (which allowed the publishers, instead of book merchants, to set the prices consumers paid for books), they could boost retail prices and force Amazon to stop competing on price. This would cut into Amazon's lead and also enable Apple to make a healthy 30-percent cut on e-book sales.

At the time, Amazon owned an estimated 90 percent market share. After the publishers switched to the agency model that share would plummet to 60 percent.

The real challenge was to get all the publishers to participate, the DOJ alleges. If one or more refused, the whole plan broke down. Publishers who chose to go the agency route alone would risk selling books at a higher price than competitors.

When the government's lawyers filed their suit, they presented a startling amount of detail about secret meetings and discussions they said occurred between the publishers and Apple leading up to the unveiling of the iPad in January 2010.

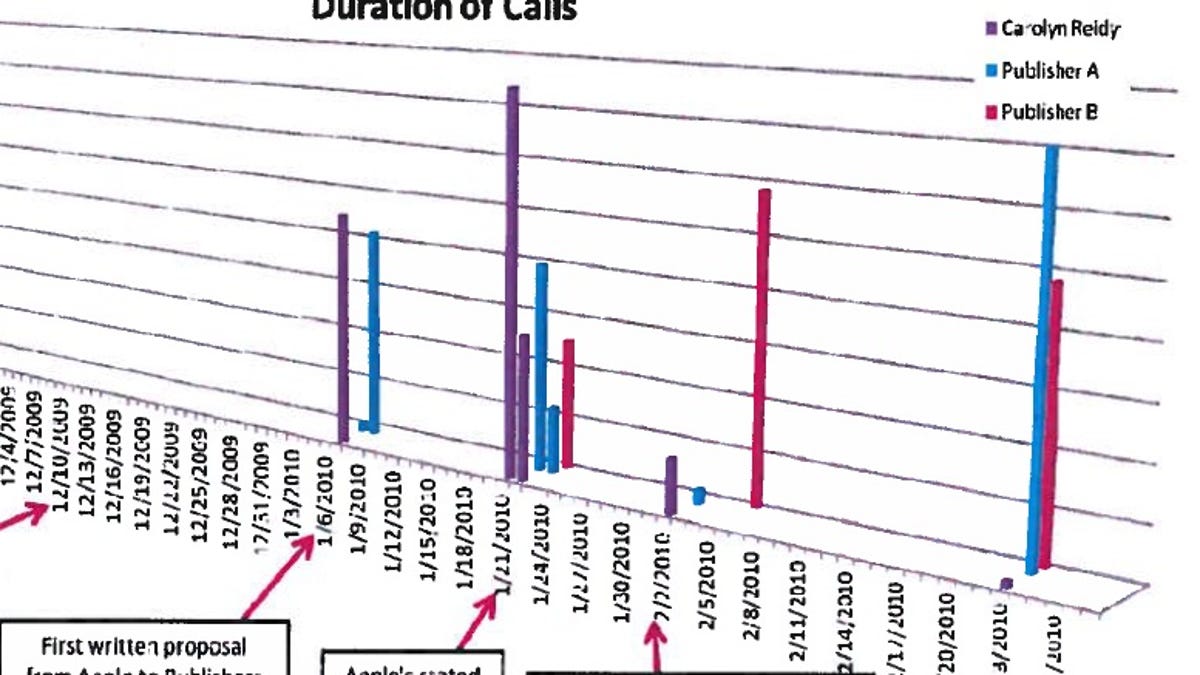

They said they had dozens of e-mails, the name of a Manhattan restaurant where CEOs from the publishing companies met, and in the state's complaint (filed the same day as the DOJ's) were charts illustrating the many phone calls made between the defendants. The government even claimed to know some of what was said. During these meetings, there wasn't an antitrust attorney present, DOJ lawyers made sure to note.

If you were like me, then you may have thought after reading about this that Apple and the publishers would eventually offer some good reason for these contacts. Who doesn't know that it looks bad -- real bad -- anytime competitors meet together to discuss pricing or share information?

Here's what I'm talking about: My music-industry sources say leaders at the four top record companies are involved in several joint ventures and they don't discuss so much as what's for lunch without an antitrust lawyer present. But in the papers Apple and the publishers filed with the court, a good explanation about why it was OK for them to meet and talk about pricing was conspicuously missing.

Apple and the publishers told the judge that she should toss the case because the Justice Department didn't offer any proof, and that the publishers each decided to switch to the agency model on their own. MacMillan's CEO, John Sargent, for example, issued a statement saying he made his "lonely" decision while on an exercise bike on January 22, 2010, and that there was no collusion. What he didn't say, according to the complaint, was that prior to making that decision, he had been exchanging information with competitors about whether they planned to move to the agency model.

Not only did the judge disagree with the legal arguments offered by Apple and the publishers, she also made it clear that she didn't find their explanation about what occurred credible.

No agency contract, no books

The judge noted the "rapid and simultaneous switch" to the agency model "by multiple competitors" after those companies spent the previous 100 years selling books wholesale to retailers and had allowed them to set prices. She didn't think that it was plausible that all of the publishers would do this at one time without "a firm understanding with [their] rivals that they would do the same."

As for Apple, she was blunt: "In short, Apple did not try to earn money off of eBooks by competing with other retailers in an open market," Cote wrote in her decision. "Rather, Apple 'accomplished this goal by [helping] the suppliers to collude, rather than to compete independently.'"

The judge found the quote Apple co-founder Steve Jobs gave his biographer about his company's dealings with book publishers was good support for the government's case. Apple's lawyers argued that Jobs was only making a prediction about what would occur in the e-book market as a result of Amazon's discount pricing. As you read this now-famous quote, ask yourself if Jobs is talking hypothetically:

Amazon screwed it up. It paid the wholesale price for some books, but started selling them below cost at $9.99. The publishers hated that -- they thought it would trash their ability to sell hard-cover books at $28. So before Apple even got on the scene, some booksellers were starting to withhold books from Amazon.

So we told the publishers, 'We'll go to the agency model, where you set the price, and we get our 30 percent, and yes, the customer pays a little more, but that's what you want, anyway.' But we also asked for a guarantee that if anybody else is selling the books cheaper than we are, then we can sell them at the lower price too.

So they went to Amazon and said, 'You're going to sign an agency contract, or we're not going to give you the books.'...Given the situation that existed, what was best for us was to do this Aikido move and end up with the agency model. And we pulled it off.

All of Apple's troubles with this case boils down to this: Amazon got the jump on Apple, when it launched the Kindle e-reader in 2007.

At a time when Steve Jobs was telling The New York Times that e-readers didn't have a future because people didn't read anymore, the Kindle was setting e-book sales on fire. Amazon only strengthened its grip on the market by making $9.99 the de facto price of e-books. While Apple prepared to get into the game, it saw that Amazon's discounts had squeezed the profits out of selling e-books.

But what Apple did with its so-called Aikido move was flip consumers to the mat. If Amazon posed a threat to book retailing, or if the company's pricing strategy was predatory, then someone should have gone to the courts or authorities.

A few people carving up a burgeoning industry for themselves in a backroom deal wasn't the answer. It wasn't fair to consumers.