Rocket scientist tells hackers to take big risks

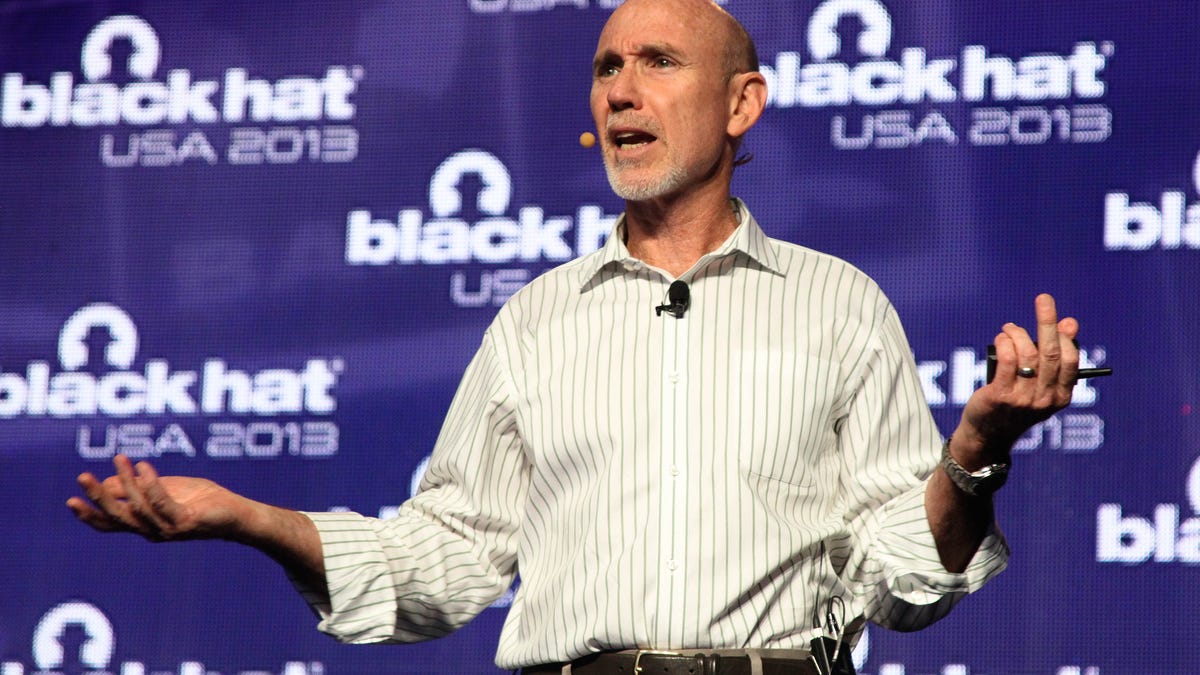

Brian Muirhead of NASA's Jet Propulsion Lab tells security professionals at Black Hat that failure is not an option when taking big risks, but offers tips on avoiding it.

LAS VEGAS -- What's the difference between building a successful computer security company and going to Mars?

If you ask Brian Muirhead, who has been instrumental in building and landing Mars rovers for NASA, there's not much difference at all.

Muirhead shared the lessons he's learned about team building during his second-day keynote speech at the annual Black Hat security conference on Thursday.

It's not rocket science -- when building a company you need to take on uncomfortable and unexpected risks and challenges, the self-described "card carrying rocket scientist" told the crowd.

"Take risks, but do not fail" was the advice given to him by a CEO of an $18 billion company that he didn't name.

Muirhead is best known for his accomplishments guiding the teams that have landed several rovers on Mars, including Sojourner in 1997, Spirit in 2004, and last year's Curiosity.

Challenging goals, like landing on Mars, require assembling the right group of people. "It's the team, stupid," he said, referencing former President Bill Clinton's famous aphorism. The members of that team, if chosen properly, can help you avoid catastrophic failures.

Talent is pretty easy to buy, he said, but trust is more important. "The team has to trust each other, and management has to trust them."

He went on to explain that the various teams involved in building the Curiosity rover had to trust each other to get work done. The team of women he affectionately called the "Seven Dwarfs" who wired the rover's guts had to be trusted by the other groups working on the project.

Management, he said, had to trust the engineers when they suggested the now-famous "sky crane" concept for landing the rover safely. And the rover landed successfully because it was built and guided by a "diverse workforce in skills, experience, and networks."

Among the several engineers in the Jet Propulsion Lab that Muirhead highlighted was Tom Rivellini, whom he said had recently quit the lab to go work for Apple. Of Rivellini's contributions to Curiosity, he invented the world's largest extraterrestrial parachute to slow down the rover before the retro-rockets were fired.

"What made Tom successful was EQ, emotional intelligence. When I'm looking for talent today, I'm looking for EQ," Muirhead said. "I want people who have that drive."

Besides building a team of talented people with high emotional intelligence who trust each other, Muirhead emphasized the importance of testing and building robust systems.

"The key to success is test, test, test. Testing is fundamental to our success," he said. There's also a component of planning for "unknown unknowns," Muirhead explained.

Not only did the lab invent the innovative extraterrestrial landing parachute, but it also developed a system of retro-rockets that slow the landing to a near-hover, 2 mph. The multiple methods of slowing the landing might seem redundant, but in fact wound up preventing the creation of a potentially instrument-damaging dust cloud.

The importance of not failing, Muirhead said, is not that you don't encounter setbacks. There are smaller failures that you learn from and fix, to avoid the bigger failure of an entire project.

At the question-and-answer period at the end of the keynote session, one audience member elicited possibly the most revealing of Muirhead's views.

"What do you think about crowdsourcing NASA?" a man asked.

"I'd love it, Muirhead said. "The key problem is funding. Unfortunately, these missions are expensive. We know there's a lot of public support -- the problem is Congress. Congress is the primary supporter of NASA, and in this environment it's been very difficult to get funding," he lamented.

Perhaps Muirhead could teach Congress some team-building techniques, to help ensure that the Jet Propulsion Lab retains its funding.