How corporate bickering hobbled better Web audio

Microsoft helped create new technology for improving online audio and speech. Now the company's fighting against it. How'd that happen?

For more than three years, Skype has worked to improve online audio through involvement in a project now called Opus. But perversely, Skype's new owner, Microsoft, is undermining Opus just as a Web standards effort is poised to carry it into the mainstream.

Opus is an audio "codec" -- technology to encode and decode media streams for efficient transmission over the Internet or storage on computing equipment. Opus backers besides Microsoft's Skype division include Google, Opera, and Mozilla.

Opus has a lot of potential to improve online audio, something that's increasingly important as more communications and entertainment move online. But the Internet is littered with codecs that faltered when rivals clashed over support or when patent land mines exploded, and it turns out Microsoft itself has thrown a wrench into the works by trying to put the kibosh on a new standard that uses Opus.

That standard is called WebRTC, and it's designed for browser-based voice communications and videoconferencing. Mozilla, Opera, and Google are all building WebRTC support into their browsers.

And at the end of July, the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) accepted a proposal (PDF) to make Opus a required codec for WebRTC by "strong consensus," Opus backers said on the codec's Web page. "This means that all browsers that implement that standard will have to ship Opus support."

But just three days after that endorsement, Microsoft -- which has plenty of clout in this debate -- notified the standards world of a very different plan.

Microsoft doesn't like WebRTC, and it, proposed a WebRTC rival called CU-RTC-Web, short for the unwieldy label of Customizable, Ubiquitous Real-Time Communication over the Web.

And one of Microsoft's criticisms of WebRTC bodes ill for hopes of an Opus shoo-in: "A successful standard cannot be tied to individual codecs, data formats, or scenarios. They may soon be supplanted by newer versions that would make such a tightly coupled standard obsolete just as quickly. The right approach is instead to support multiple media formats..." If Microsoft gets its way, WebRTC won't prevail, and whatever does might well offer a choice of codecs rather than mandating Opus.

Opus could still have a place in Web-based communications. First, though Microsoft criticized WebRTC's ties "to individual codecs," it didn't rule out Opus specifically, and of course Skype helped develop it in the first place. Second, Microsoft's individual-codec complaint is subordinate to broader concerns that WebRTC "shows no signs of offering real-world interoperability" and has "no fit with key Web tenets." Last, Microsoft can be more easily bypassed since other operating systems and browsers have eroded the power of Windows and IE.

Such debates are par for the course in standardization. But the debate is hardly likely to hasten Opus' arrival.

Two codecs in one

Opus is actually two codecs rolled into one to span a wide range of situations. The first is for Internet videoconferencing and voice calls, where immediacy is paramount, and the second is for music, where quality is more important. The first situation means it's easier to understand the person on the other end of a voice over Internet Protocol (VoIP) chat, even if you're on a slow mobile-phone connection, and that you aren't as likely to have to put up with conversation-disrupting lags as the codec catches up with what people are saying. The second situation is the sort of thing a music streaming service like Spotify or Pandora could appreciate, but also video sites such as YouTube, because audio codecs are paired with video codecs.

Opus' dual-use approach leads co-creator Jean-Marc Valin, who works for Mozilla and the codec-focused Xiph.org Foundation, to call it "the Swiss army knife of audio codecs."

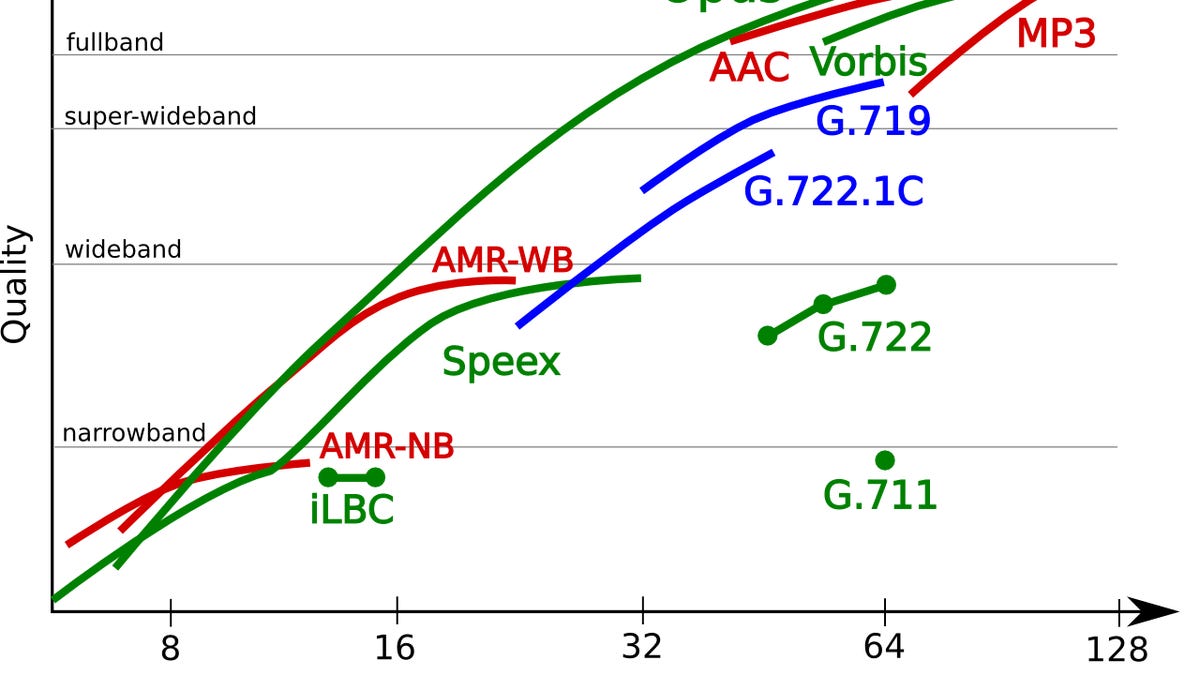

An all-purpose tool has a lot of appeal. The IETF considered 10 other codecs, but none of them had Opus' flexibility and liberal licensing. Opus' sound quality is "equal or better than state of the art at the vast majority of bitrates and audio bandwidths," the IETF proposal said, and the IETF explicitly favors shipping software over mere ideas.

The first of Opus' codecs derives from a Skype project called Silk. It's designed for voice communication where there isn't much bandwidth available, Valin said. The second, called CELT (constrained-energy lapped transform), originated at the Xiph.org Foundation that's long worked on royalty-free codecs, and it's designed for high-quality audio such as music in situations where there's more bandwidth available. The two codecs can work together in a hybrid mode, too, for example for higher-quality speech.

Codecs encode and decode video or audio so they can be stored or transmitted in a more compact compressed form. They're profoundly important standards when it comes to the multimedia Internet, as demonstrated by the MP3 audio codec that revolutionized digital music.

Codec politics

It's hard to get the whole tech industry marching in lockstep so all necessary parties support the same codecs. Political and technical disagreements have led to dividing lines such as H.264 vs VP8 for video, and audio alternatives such as AAC have failed to dethrone MP3 despite sound quality and compression improvements.

Codec politics are complicated by the fact that so many parties are interested: codecs are needed for everything from video cameras and mobile phone processors, from browsers to operating systems, from TV broadcasts to Blu-ray discs. Layered on top is a thorny tangle of intellectual-property licensing concerns, with companies licensing their own patents or offering them through the MPEG LA organization.

WebRTC -- short for real-time chat -- has the potential to unify codecs in at least one corner of the industry. WebRTC support will mean browsers can handle videoconferencing and VoIP tasks that today typically use dedicated software such as Skype or Gmail Chat's browser plug-in.

Two weeks ago, Google proposed that Opus become a required audio codec for WebRTC.

"We believe that Opus should be the default mandatory-to-implement audio codec, assuming the remaining licensing issues can be resolved. Opus delivers excellent quality, from narrowband to fullband, for streaming and real-time, making it an ideal choice for a baseline codec," said Google's Justin Uberti in a mailing list message to the IETF, which along with the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) is standardizing WebRTC.

"Licensing issues"? Google wouldn't comment for this story, but in a Google I/O talk about WebRTC, Uberti said, "We hope to support Opus, assuming that Microsoft can help us out on the licensing front."

Mozilla seems less concerned. It ships Opus in Firefox 15, currently in beta testing. But it's not tipping its hand: "We are currently in discussions with a number of companies regarding Opus but don't have anything to announce right now," Mozilla spokesman Mark LaVine said.

Microsoft also isn't revealing its Opus plans, saying in a statement that it has "nothing to share on implementation of the codec or future plans at this time." Opera, though, said it has both WebRTC and Opus support on its road map.

Standards indigestion

Uberti also proposed Google's royalty-free VP8 be a required codec for handling the video side of WebRTC communications. That could be a harder sell, given how difficult a time Google has had finding allies for WebM, which combines VP8 video and an older audio codec called Vorbis. H.264 remains very widely used and supported as a video codec, despite its patent royalty constraints, and has proved hard to compete against. Mozilla, a strong advocate of royalty-free codecs and Google's most prominent VP8 ally, eventually threw in the towel and began adapting Firefox so it could draw on an operating system's H.264 support.

This divide shows no signs of fading now at WebRTC. "Not only is there still no consensus over which codec to use (VP8 vs H.264), but there's also been no significant progress in getting to a consensus," Valin said after the IETF meeting.

The disagreement recapitulates another that's brewed for years regarding HTML5 audio, where factions were split along the same lines. The result is that video built into Web pages doesn't specify a codec, and Web developers must make sure the one they use is compatible with different browsers. H.264 mostly won that battle, but it left hard feelings and in effect built a royalty-encumbered technology into the foundations of the Web.

Opus could well have a place in whatever real-time chat standard emerges, especially given Skype's involvement creating Opus. But even though Chrome, Opera, and Firefox are WebRTC fans, noncooperation from Microsoft poses serious obstacles to would-be Web standards. For example, Internet Explorer doesn't support the 3D graphics interface called WebGL, despite enthusiasm from Chrome, Opera, and Firefox. That limited support means Web developers can't count on its being available.

Microsoft's CU-RTC-Web proposal looked to some like it was more in keeping with sabotage than constructive criticism.

"I see that Microsoft decided to wait until the W3C and IETF [standards groups] were close to done before putting together a proposal that, if accepted, would explode most of the current works and create maximal delay on this work," said Cullen Jennings, a Cisco representative on the W3C's Web Real-Time Communications Working Group.

And Eric Rescorla, who helped write the WebRTC support in Chrome and Firefox and who is consulting for Mozilla, posted a rebuttal of Microsoft's CU-RTC-Web proposal (and a suggestion to pronounce it "Curtsy-Web").

But standards groups can achieve harmony, too. Back when Silk and CELT were separate projects, Skype's effort to standardize Silk through the IETF in March 2009 ran into passionate disagreements.

"To say that the proposal was controversial would be an understatement," Valin said in a January speech. "There were big fights about that."

But Opus eventually bridged the divide, showing that rifts evidently can be healed. Perhaps the Web communications standards camps will come together, too, easing Opus' arrival onto the Net.