Otellini's legacy at Intel: Plentiful profits, mobile misfires

When Intel's CEO since 2005 retires next year, the company will still face a problem it's barely begun to solve: finding a foothold in the mobile market.

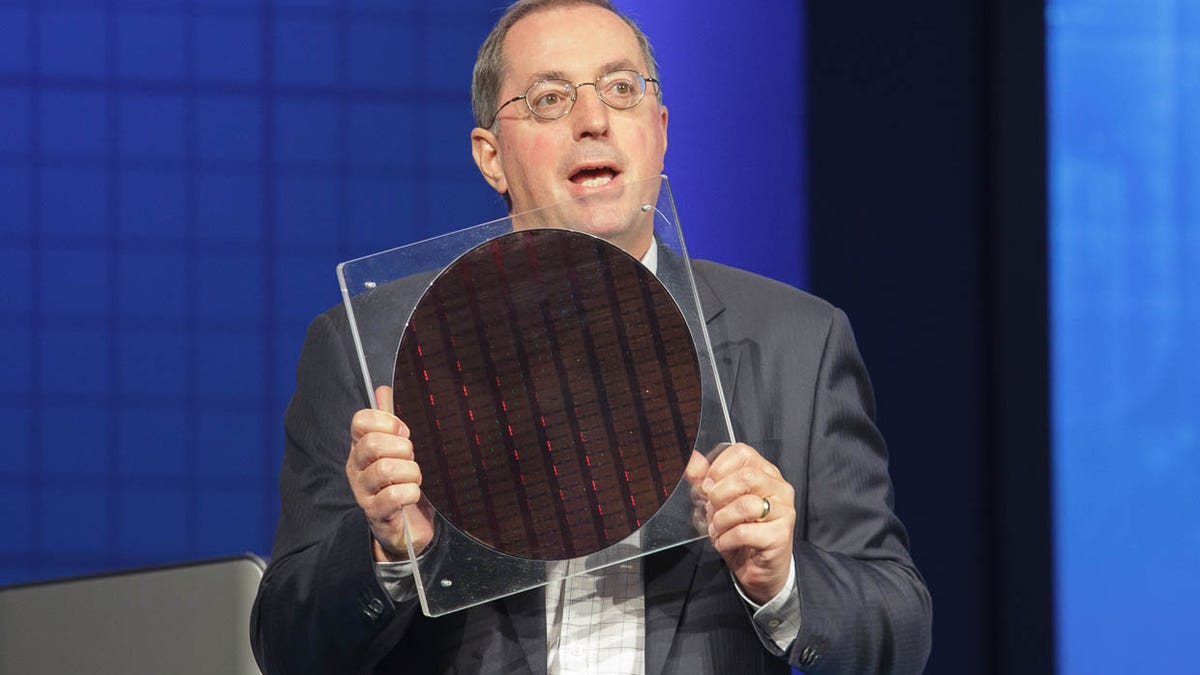

When Intel CEO Paul Otellini retires in May, he'll leave a mixed record.

On the one hand, Intel's processor manufacturing prowess remains second to none, with the company often introducing new miniaturization technology years ahead of rivals. As ever more companies withdraw from chip manufacturing, Intel manages to keep turning the crank profitably. During Otellini's reign, Intel has so far generated $107 billion in cash from operations and paid dividends of $23.5 billion.

But Intel also has failed to come to terms with a powerful force in the processor world -- the rise of mobile devices using low-power ARM processors. These are the chips that power every iPhone and iPad, almost every Android device, and the new Microsoft Surface tablet.

It's an embarrassing absence for Intel. The company has gained a tiny foothold with its Medfield generation of processors, which are used for example in Motorola Razr i phone and some other products. But mostly, Intel is conspicuous in this market by its absence from a market that is both large and fast-growing.

Under Otellini, an Intel insider who became CEO in May 2005, the company has faced many chip challenges.

In the days when he was coming aboard, Advanced Micro Devices was strongly competitive, having made the jump to 64-bit x86 processors as Intel was still bogged down with its ill-fated and incompatible Itanium family. Intel recovered its poise and now is the driving force in the x86 server market.

Intel also wrestled with the power wall -- the unpleasant reality that new processors couldn't run at faster clock rates without devastatingly high levels of power consumption and waste heat. The answer has been a push toward multicore processors, spreading computing out over multiple processing engines working in parallel.

ARM'd incursions

But the mobile challenge has been intractable for Intel, and though the company's fortunes may improve in coming months, it's a certainty that the company will only be a challenger at best in the mobile market. ARM processors are just too pervasive.

For many years, Intel benefited from the fact that it's hard to move software from one processor architecture to another. That's in part what made Itanium such a hard sell, why AMD could ride on Intel's coattails with x86 chips, and why Microsoft Surface is such a departure from ordinary Windows devices running on x86 machines.

Software compatibility is only useful if you're on top, though. Now with mobile devices, ARM has the advantage. iOS software is written to run natively on the ARM chips in Apple's devices. And although Android apps use a higher-level abstraction layer called Dalvik that insulates many programs from the particulars of a chip instruction set, a good many programs also use Google's Native Developer Kit (NDK) so programs speak directly to ARM processors. That's especially true when programmers want the highest performance.

And ARM is rising. Now Samsung and Google have releasd an ARM-based Chromebook, and rumors persist that Apple could release ARM-based Macs.

ARM licenses its processor designs to others that combine them with modules for things like graphics, input-output, and video decoding into processor designs called system-on-a-chip, or SOC. The company got its start in 1990 as Advanced RISC Machines, a spinoff from Acorn Computer Group that combined with Apple's effort to obtain a processor for its Newton handheld computer. After years in the shadows, ARM processors are now hot.

Now the ARM action is elsewhere. Qualcomm, Nvidia, Samsung, Apple, and many others design chips with processing engines. Even AMD, no longer manufacturing chips of its own, has caught ARM religion.

ARM, in a way, is doing to Intel what Intel did to higher-end competitors in the processor market. If lower-cost chips can get the job done, they can relegate higher-end competition to expensive machines that ship only in low volume. And for a chipmaker, manufacturing volume is crucial to profitability.

Note, too, that ARM chips are making the jump to 64-bit chips, and the new ARM Cortex A15 models are designed for computers that need more horsepower.

The irony here is that Intel once had a competitive ARM design. It was called StrongARM, later XScale, and it picked up the asset from legendary computer designer Digital Equipment Corp. (DEC) when Compaq acquired it in 1998.

StrongARM was clearly on the periphery of Intel's business priorities, but it wasn't irrelevant. As an exercise in pondering what might have been, remember that Intel showed off a StrongARM-based tablet in 2001.

Intel can be forgiven for not investing in StrongARM and XScale, a division it sold off in 2006. The Itanium lesson in the perils of incompatible chip designs was expensive.

But it's not so easy to forgive Intel for not building a competitive x86 processor for mobile devices. The Atom designs are a start, and they have a place in Windows tablets and lower-end computers. But Otellini's successor will have to make them into something much greater.