One Thing We're Getting Wrong About AI

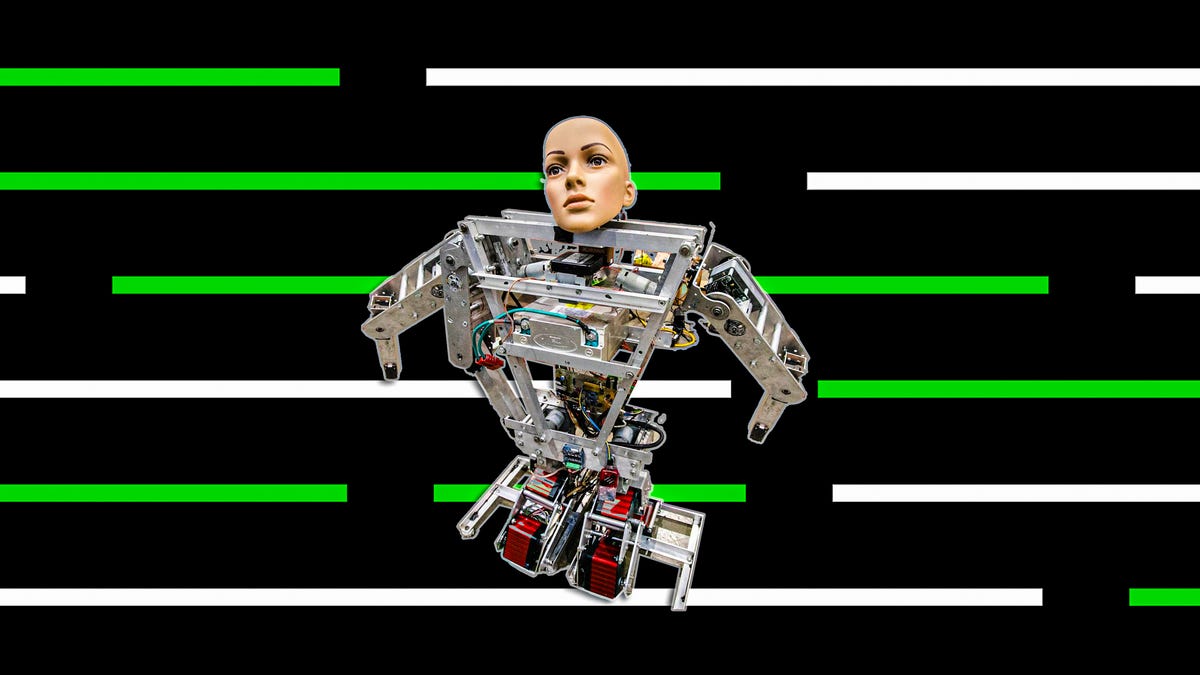

At SXSW, discussions focus on the promises and pitfalls of the technology, including the very human bias to assign consciousness where it doesn't exist.

Machine learning and AI

As artificial intelligence has captured imaginations with instantly generated images of surfing giraffes or poems of depressed bowls of ramen, AI tech seems to be popping up everywhere, getting smarter by the minute.

You may find that fascinating or frightening, or maybe a little of both. It's disruptive for sure — just look at ominous headlines in recent months like As AI Advances, Will Human Workers Disappear? and Why A Conversation With Bing's Chatbot Left Me Deeply Unsettled.

So it's no surprise that AI has been a hot topic at this year's SXSW conference, going on right now in Austin, Texas. The conference is tuned in to the cutting edge, bringing together thought leaders, executives and artists across the business, tech and entertainment sectors. Attendance doesn't yet feel like it's back at pre-pandemic levels, with meeting rooms more than half empty at times, but it still has had a decent mix of panels and talks on everything from the metaverse economy to music in anime.

For those working in AI who turned up at SXSW, there was an uneasiness about the pace at which the technology is proliferating. And there was a feeling that the public hasn't yet come to grips with AI's surging prominence, and the things it can do, in the tech they touch every day. It's all too easy to fall into sci-fi tropes and to project personhood when it isn't there. The sentiment was clear: Be prudent.

"Before telling the world your AI is sentient, maybe ask a friend," said Jason Carmel, global creative data lead who specializes in AI at Wunderman Thompson, a New York-based advertising firm. Speaking during a presentation on sentience and AI on Tuesday, Carmel argued that the sensationalizing of AI — see those headlines above — will create misunderstanding and ultimately lead to fear and a loss of trust.

This new wave of worries about AI kicked off with November's launch of OpenAI's ChatGPT, a chatbot built on a powerful AI engine that promises to revolutionize how we get information from the internet. ChatGPT proved incredibly popular right from start: By January, it reached over 100 million active users, making it the fastest growing web platform ever.

Since then, there's been a rush of Big Tech companies looking to capitalize on that breakthrough. Microsoft announced a multibillion-dollar expanded partnership with OpenAI to bring ChatGPT tech to its Bing search. Google — maker of the world's most popular search engine — responded by revealing its ChatGPT rival, called Bard, and just this week unveiled new AI capabilities for apps like Gmail and Google Docs. And Microsoft's suite of software for work won't be left behind either, as the company said it'll bring an AI-powered "co-pilot" to Word, Excel, PowerPoint and more.

Also joining the AI rush: search engine DuckDuckGo, social media app Snapchat, writing assistant Grammarly and Meta's messaging apps WhatsApp and Messenger.

What makes ChatGPT and similar tools accessible for the average person is their conversational style and their ability to write everything from travel itineraries to work emails to college essays in a convincingly human way.

That skill can help people accelerate research and work dramatically, and the tools will be "orders of magnitude more impactful than the smartphone," said Rahul Roy-Chowdhury, global head of product at Grammarly, during a panel on the future of AI on Tuesday.

But those on the AI panels at SXSW worry that machine-driven talents are leading people to assign humanlike individuality and intelligence to a technology that's simply good at presenting existing information in a novel way. People then can fall prey to biases in that information and may not understand when it's incomplete. The tech can sometimes confidently present incorrect information as true, referred to as hallucinations. And there's concern companies are rushing out these AI-infused services without building in sufficient ethical safeguards. Microsoft reportedly laid off its AI ethics and society team when the company cut 10,000 positions in January, though it says it's committed to developing AI products safely and responsibly.

We've already seen what happens when people prematurely assign awareness within machines. Last year, Blake Lemoine, a Google software engineer, claimed that a chatbot being tested within the company had achieved sentience. His proclamation was quickly met with imagination-grabbing headlines and derision from AI experts, describing it as "nonsense."

"The patterns might be cool, but language these systems utter doesn't actually mean anything at all," said AI scientist and author Gary Marcus in a Substack post last year. "And it sure as hell doesn't mean that these systems are sentient."

Google fired Lemoine a month later for sharing internal information.

What we're getting wrong

For Carmel, people have been conflating sentience with intelligence. Intelligence is being able to collect and apply information, whereas sentience requires the ability to feel and perceive things. And consciousness takes it a step further, having a level of self-awareness. Often, Carmel feels, people describe AI as being sentient when it's really just good at regurgitating information.

"What I would seek to change is [people's tendency toward] humanizing AI in a way that adds emotion where emotion shouldn't be," said Carmel. He pointed to journalists using words like "lobotomized" to describe changes to an AI's code. "It gives people the wrong idea of what's actually happening. And it makes the developer's job so much more difficult too."

Carmel isn't saying that we should stop using metaphor and hyperbole to describe complex topics around AI, but rather that figures of speech can add emotional baggage to an otherwise useful tool.

To help combat misconceptions, the team at Wunderman Thompson created the Sentientometer, a website that's essentially a series of checklists to break down whether an AI is sentient. ChatGPT didn't even come close.

When it comes to verbiage, Grammarly's Roy-Chowdhury says the world "artificial" in AI misconstrues its core objective. He would prefer we call it "augmented intelligence," in that it builds on our ability to gather and perceive information. The term "artificial" pulls people into sci-fi conversations about consciousness and sentience, when it's really more about helping people perform specific tasks.

The team at Wunderman Thompson wants researchers to embed ethics into AI early on. This includes coding AI to not do "bad stuff," to be fair, to understand potential impacts and to be transparent. And, to put it bluntly, programmers should tell these tools to make sure they "don't hurt humans." That is, Carmel said, AI technologies should be taught about human rights so that as AI evolves, it'll carry these concepts with it.

Though the presenters at SXSW were generally optimistic about the future of AI, they said nothing beats a human touch.

That's the essence of good non-AI-generated writing.

"Personally, knowing this is a human who put work into the story, it has so much value for me," said Ilinca Barsan, director of data science at Wunderman Thompson, who co-presented the discussion with Carmel. For Barsan, learning that something was AI-generated removes some charm, and she said she'd never want to read a novel written by AI.

"That's the magic of art and music and literature," said Barsan. "It's a human experience. And you're getting one person's specific view of the world," whereas AI simply gives us "everything mashed together."

Editors' note: CNET is using an AI engine to create some personal finance explainers that are edited and fact-checked by our editors. For more, see this post.

Correction, 8:45 a.m.: Ilinca Barsan's last name was spelled wrong in the original version of this story.