How people with Down syndrome are teaching Google

Working with the Canadian Down Syndrome Society, Google is collecting voice samples to teach its Google Assistant to understand people with the condition.

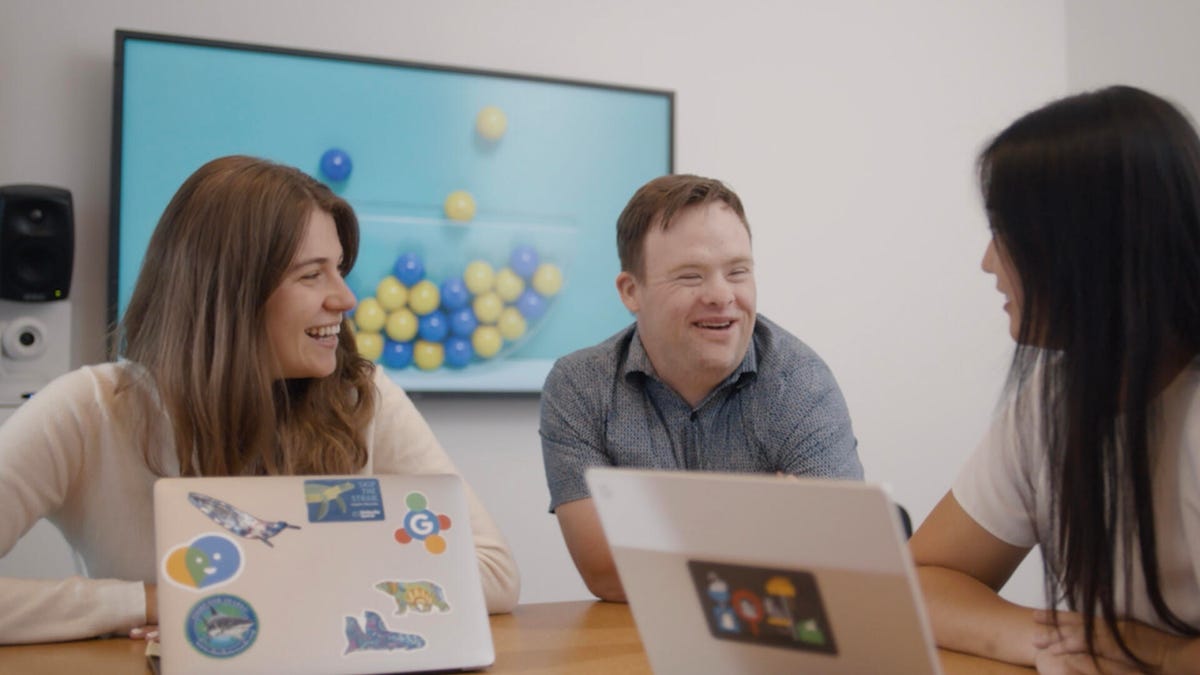

Matthew MacNeil is one of more than 600 adults with Down syndrome who have donated their voices to help Google improve its speech recognition technology.

When Matthew MacNeil uses the voice-to-text feature on an Android phone, the resulting transcription looks nothing like what he said.

"Hello, my name is Matthew MacNeil. I live in Tillsonburg, Ontario," becomes "Hello my name is Master MacNeil. I live in traffic Ontario."

MacNeil, who is 30, has Down syndrome, and he's often frustrated that voice technology, like the Google Assistant , on smartphones doesn't always understand what he's saying. MacNeil, who lives independently with two roommates, relies on voice assistants on his personal devices to log the hours he works each week at his local supermarket, Sobeys. He also uses it to set timers for his workouts at home.

But the technology doesn't always work well.

"It's always autocorrecting what I say," he said in an interview with CNET. "And I'm like, 'I didn't say that. I said this.'"

For many people, voice assistants such as Amazon Alexa , Apple's Siri or Google Home offer an easier way to check the temperature outside or to cue up their favorite tunes for an impromptu dance party. For people with Down syndrome, it can be life-changing technology.

It's a tool that can help them manage schedules, keep in touch with friends and family or get help in an emergency. In short, it can make independent living more possible. Still, for many people with Down syndrome, being understood is a struggle. And that limits how they can use this technology.

For MacNeil, the issue isn't just about fixing a technical glitch, it's about equity and inclusion for people with Down syndrome and others who struggle to be understood. MacNeil says he's just like everyone else. He went to school. He works. He hangs out with his friends. And he wants to make sure that big tech companies make products he can use.

"It definitely helps me feel more independent," he said. "I want to be able to use technology like everyone else."

MacNeil is doing something to make sure more people get that feeling. He is part of a collaborative effort between Google and the Canadian Down Syndrome Society called Project Understood, which is collecting voice samples of people with Down syndrome to improve its Google Assistant technology. It's an offshoot of Project Euphonia, a program announced at last year's Google I/O that uses artificial intelligence to train computers to understand impaired speech patterns.

It's not a problem that's isolated to Google's voice recognition product. For MacNeil and others with intelligibility issues, voice assistants often get it wrong. The reason is simple: The samples used to train AI technology often include voices from people with typical speech patterns. The goal of Google's project, which is still in research and development, is to train computers and mobile phones to better understand people with impaired or atypical speech patterns.

Left behind

There were an estimated 2.5 billion digital voice assistants used worldwide in devices like smartphones, smart speakers and cars at the end of 2018, according to Juniper Research. By 2023 that number is expected to increase to 8 billion, which exceeds the world's population.

Amazon Alexa, Apple's Siri and Google Assistant can be powerful tools to help these individuals live more independently in their communities, says Brian Skotko, a physician who is co-director of the Down Syndrome Program at Massachusetts General Hospital.

Skotko said it's common for people with Down syndrome to struggle with activities of daily living, such as knowing when to take medications, keeping track of their schedules or handling money.

"Sometimes people with Down syndrome need a little bit of help," he said. "But what they're demonstrating is that with the right resources and support, they can conquer those challenges."

He added that smart technologies can be very useful in offering those supports.

"A voice assistant is just one more way of equalizing the opportunity for people with Down syndrome," he said.

Google has been working on accessibility issues for several years in an effort to ensure its products are accessible to all. The Google Maps team has launched a program to use local guides who scout out places with ramps and entrances for people in wheelchairs. Last year, Google released the Android Lookout app, which helps the visually impaired by giving spoken clues about the objects, text and people around them.

The effort by Google is also part of a broader trend among big tech companies to make their products and services more accessible to people with disabilities. Digital assistants, in particular, have gotten a lot of attention, as companies like Amazon enhance their products to make them accessible to users who are deaf or have other disabilities.

Skotko said it's important for technology companies, like Google, to involve the disability community in developing these tools to make sure they aren't left out.

"If people with Down syndrome are not included in the creation of technology, we run the risk of creating a technology that doesn't meet their needs," he said.

People with Down syndrome are asked to record 1,700 phrases to help train the Google software to understand atypical speech patterns.

From Project Euphonia to Project Understood

This is where Google and the Down syndrome community have come together.

Initially, Project Euphonia was focused on gathering voice samples from individuals with ALS, a progressive neurodegenerative disease that affects nerve cells in the brain and the spinal cord and often leads to slurred and impaired speech. Google's software takes recorded voice samples from people with ALS and turns them into a spectrogram, or a visual representation of the sound. A computer then uses common transcribed spectrograms to train the system to better recognize this less common type of speech.

Meanwhile, the Canadian Down Syndrome Society was developing its annual awareness campaign, which it runs every November. The nonprofit advocacy organization surveyed members who have Down syndrome and realized a common theme. Like MacNeil, many in the Down syndrome community were frustrated that their voice activated technology didn't understand them, and they wanted tech companies to take action to make their products more inclusive.

So the society contacted Google to offer its help in collecting samples of people with Down syndrome. And thus Project Understood was born.

MacNeil, who chairs the self-advocate committee at the Canadian Down Syndrome Society, traveled to Google's headquarters in Mountain View, California, last fall to be among the first to lend his voice for the project.

"I was really happy that Google invited me to its headquarters, because it really tells me that they want to help us build awareness," MacNeil said. "And they really want to make [their technology] better."

Since launching Project Understood in November, Google has reached its goal of collecting more than 600 voice samples from adults with Down syndrome. And it's still accepting samples through the Project Understood link. Currently, Google is only collecting voice samples in English.

The tech challenge

Those samples are critical because the algorithms used to train voice assistants are based on what's known as "typical speech." That's why people with Down syndrome, ALS or other conditions affecting speech have a tough time with assistants.

Google Assistant misses about every third word spoken by a person with Down syndrome. To train the software to understand atypical speech patterns, Google needs more samples. This is where Project Understood comes in. Individuals with Down syndrome are asked to record about 1,700 phrases, such as "Turn left on California Street," "Play Cardi B" or random phrases like "I owe you a yo-yo today," all in the hopes of generating enough data for the machine learning algorithms to find patterns that can be used to improve accuracy.

"The more voice samples we can collect, the more likely Google will be able to improve speech recognition for individuals with Down syndrome and anyone else," said Julie Cattiau, product manager at Google.

Cattiau said the "dream is to have Google assistant work out-of-the-box for everyone." But she admitted that may not be possible due to the variability in atypical speech patterns. Alternatively, digital assistants may require extensive personal customization.

Cracking the personalization issue, Cattiau said, requires not only more machine learning data, but also innovations in data analysis.

Google has hired four speech language pathologists who are helping AI engineers to understand the nature of speech patterns and to figure out how to group data sets to find patterns.

"We're engineers," Cattiau said. "We don't know anything about the underlying conditions that exist and what that means for speech and language. That's where the SLPs have been so helpful."

The legacy of Project Understood

Project Euphonia and Project Understood are still research projects within Google. It could take years for anything learned to make it into a Google product, if it ever does. But Ed Casagrande, chair of the board of directors for the Canadian Down Syndrome Society, who has a 6-year-old daughter with Down syndrome, said he's optimistic about what this work could mean for her future.

Casagrande, like many parents who have children with disabilities, thinks a lot about the life his daughter will live as an adult. He wants her to have the same opportunities in her life as her siblings without disabilities. But he knows she's likely to need more support to live independently and to work in her community. He hopes that technology, like voice assistants, can knock down some of the barriers that may stand in her way.

"Right now, it's all about the fun stuff, like accessing movies and music," he said. "But someday maybe she'll be able to call up her self-driving car to take her to work, or the technology will be able to tell from the sound of her voice if she's sick."

The possibilities seem endless.

MacNeil said he's optimistic that his participation in Project Understood will eventually lead to improvements in voice recognition technology. But for now, he's also eager to spread the word to other big technology companies to make sure they include people with disabilities in the creation of their products.

In a video message to the United Nations for World Down Syndrome Day in March, MacNeil offered this message: "We need more than just Google to take part," he said. "Every technology company needs to make accessibility a bigger priority. We all belong. We all matter."