Justice Department bends on (some) e-mail privacy fixes

But the administration will tell Congress tomorrow that the feds need more surveillance powers over e-mail messages, Twitter direct messages, and Facebook direct messages in other ways.

The Obama administration has dropped its insistence that police should be able to warrantlessly peruse Americans' e-mail correspondence.

But at the same time, the Justice Department is advancing new proposals that would expand government surveillance powers over e-mail messages, Twitter direct messages, and Facebook direct messages in other ways.

It's a development that will complicate the political wrangling over Americans' electronic privacy rights, which are in large part protected by a 1986 privacy law written in the pre-Internet days of the black-and-white Macintosh Plus and dial-up computer bulletin board systems.

"It's like two steps forward and two steps back," says Hanni Fakhoury, a staff attorney at the Electronic Frontier Foundation. "I question how much they're really conceding."

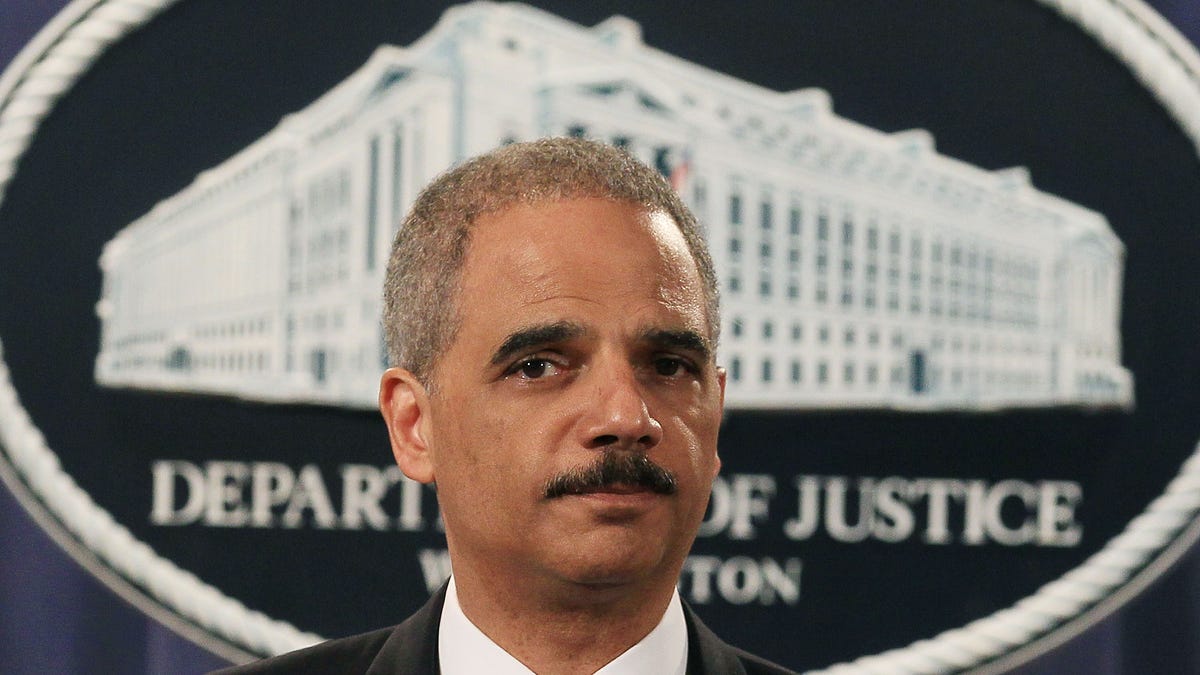

Elana Tyrangiel, a former White House lawyer who's now an acting assistant attorney general, will announce the department's new policy positions at a congressional hearing that's scheduled to take place tomorrow morning.

Tyrangiel's written testimony says the current rules -- enacted during the pre-Internet era in the form of the Electronic Communications Privacy Act of 1986 -- "may have made sense in the past" but "have failed to keep up with the development of technology, and the ways in which individuals and companies use, and increasingly rely on, electronic and stored communications."

But she also says that the department's civil attorneys investigating antitrust, environmental, civil rights and other cases -- and presumably other federal agencies such as the Securities and Exchange Commission and the Federal Trade Commission -- should have warrantless access to Americans' electronic correspondence. Patrick Leahy, the Vermont Democrat who's the chairman of the Senate Judiciary committee, floated that idea last fall, but then scuttled his proposal after a public outcry.

Until now, the Justice Department and other law enforcement groups have opposed requiring search warrants to obtain e-mail in criminal investigations. James Baker, an associate deputy attorney general, told Congress two years ago that that requiring a search warrant to obtain stored e-mail could have an "adverse impact" on criminal investigations. Last fall, police groups including the National District Attorneys' Association and the National Sheriffs' Association asked the Senate to "reconsider acting" on legislation "until a more comprehensive review of its impact on law enforcement investigations is conducted."

The department's volte-face echoes what a coalition of technology companies including Apple, Amazon.com, AT&T, Facebook, Google, and Twitter have been telling Congress for years. The coalition includes conservative groups such as Americans for Tax Reform and liberal groups including the American Civil Liberties Union and the Electronic Frontier Foundation.

"I thought that was a very welcome statement," says Chris Calabrese, legislative counsel for the ACLU. "It seems like there's a lot of common ground here and that we should be able to pass something."

The Justice Department did not immediately respond to a request for comment from CNET.

Tyrangiel is also proposing eliminating some of the privacy protections that apply to company records that reveal who is sending or receiving e-mail, Facebook, Twitter, and similar messages. Because current law allows law enforcement to "obtain records of calls made to and from a particular phone" without having to go before a judge, the same rule should allow police to obtain e-mail addressing information, she says.

"They're giving with one hand, but also taking with the other," Fakhoury says.

The Justice Department's new position is likely a recognition of political and legal forces that have been building for the last few years -- and, perhaps, a recognition that if some form of legislation is inevitable, the department should offer its own proposals too.

Last November, Leahy's committee approved by a voice vote a privacy bill that would curb law enforcement's warrantless access to the contents of e-mail, private Facebook posts, and other data that Americans store in the cloud. And in 2010, a federal appeals court ruled that police must obtain a search warrant from a judge based on the traditional standard of probable cause before accessing files stored in the cloud, including e-mail. Google, Microsoft, Yahoo and Facebook said in January that they require search warrants for e-mail.

Last updated at 6:15 p.m. PT