Play me a story: How video game storytelling has evolved

CNET Magazine: From Atari to arthouse, Bushnell to Blizzard, we hear from industry heavyweights on how games have grown up.

Has a video game ever made you cry? No? That may be because you haven't played the right game yet.

Sure, there are plenty of run-jump-shoot-repeat blockbusters, where any story driving the game is an excuse for action. But over the past decade, a few game makers have created deeply engaging stories that may bring a tear to your eye. That includes titles like That Dragon, Cancer, where you fill the shoes of parents guiding their infant through terminal cancer. That such a game even exists shows the medium can deliver nuanced experiences with real emotional impact.

"Interactive storytelling is important because we're not just affected by the art from a passive standpoint," says Leena van Deventer, a game developer, writer and educator in Melbourne, Australia. "Sometimes we're more invested in the outcomes because we have a digital representation of ourselves on screen."

But that ability to tell complex, interactive stories became possible only as computers got faster and smarter. Here's the story of storytelling in video games .

In the beginning was 'fun'

The first wave of successful video games emerged in the 1970s with the arrival of arcade machines and home consoles. Nolan Bushnell founded Atari and delivered Pong, a simple, black-and-white, tennis-like arcade game of moving blocks with simple sound effects. Given the restricted computing power of the time -- the original Atari 2600 featured just 128 bytes of memory (no kilo, no mega, no giga) -- there was room for just one idea.

Games like Pong were all about "fun and challenges," says Bushnell. "The technology was so difficult that it was exhausting to get the game to play without worrying about story. Adding themes and story concepts did not really happen until the early '80s, when you had digitized sounds and graphics that were good enough to convey an actual character."

That "fun and challenges" formula was focused at first on sports-themed games "because they intersected with known rules" of play, and worked well in arcades and bars alongside pinball machines and pool tables. Where Pong offered tennis, Atari rival Taito designed games based on hockey, basketball and soccer.

Adventure time

While those early games were pure gameplay, the first story-focused games were pure wordplay.

Text adventure games, starting with Colossal Cave Adventure, Adventureland and Zork, ran on mainframe computers and early home computers like the Apple II. Some fans called them interactive fiction because they were based on fantasy and sci-fi concepts pulled straight from the pages of Tolkien, or tabletop games like Dungeons & Dragons.

These adventure games described the scenes to you -- think paragraphs from a novel. Typing commands told the game what to do next. "Go west, use key, open door, grab sword." Examining scenes and solving puzzles allowed you to uncover more sections of the story and progress toward the conclusion.

As computers advanced, they added an important feature for gaming -- memory. Now you could save your game and pick up where you left off, allowing you to work through adventures over many days.

Maniac Mansion, the first in a long line of LucasArts point-and-click adventure games.

When graphics and graphical interfaces arrived at the end of the 1970s, adventure games brought words and pictures together in immersive adventures. The first of these was 1980's Mystery House for the Apple II. Point-and-click interfaces spared you from having to learn text commands to penetrate the stories hiding behind the code. Now you could click on words or objects to move through the game, talk to characters and solve puzzles.

In the early 1980s, George Lucas created the Lucasfilm Games division (later renamed LucasArts). It earned a reputation for going beyond the standard fantasy action tropes and delivering adventure games about subjects outside "standard high fantasy or science fiction," says Tim Schafer, who worked for LucasArts from 1989 to 2000 on the pirate-themed The Secret of Monkey Island and the film noir-style Grim Fandango.

Using a new programming system called SCUMM (Script Creation Utility for Maniac Mansion), LucasArts paved the way for designers to focus on ideas instead of code.

"Our cutting-edge technology was actually just picking genres of storytelling that were outside the currently acceptable genres of video games," says Schafer.

Building mythologies

By the early 1990s, computers were a million times more powerful than those just 10 years earlier. Game makers used that added power to create a new genre called real-time strategy. These games demanded fast thinking from players, who had to collect resources, create combat units and defeat the opposition without the option of a pause button. The result: games like Dune, based on the Frank Herbert novel.

Real-time strategy doesn't require a story, except as an excuse for combat that takes place across a series of missions. But Blizzard Entertainment, makers of 1994's Warcraft: Orcs & Humans, saw an opportunity to engage players through a story that set the stakes and offered noble reasons to fight. Players suddenly felt more connected to the action.

"That proved to us how much more meaningful and deep and immersive a game experience could be if you had that world built around it," says Mike Morhaime, co-founder and CEO of Blizzard.

Warcraft has grown to become "The Lord of the Rings" of video game fantasy world building.

Blizzard has since built more than three game universes, including Warcraft, StarCraft and Diablo, showing how games could become vehicles for stories that live and grow through updates and sequels spanning decades. Its best-known franchise, World of Warcraft, launched as an online role-playing version in 2004. Its popularity endures as its evolving story shows the world continually under threat.

"If you look back at early World of Warcraft, there was no cohesive storyline," says Jeff Kaplan, a longtime game director for World of Warcraft who now oversees Blizzard's latest title, Overwatch . "It was more, 'Here is some context for your questing actions -- go have a good time.'"

Warcraft's mythology has grown to become the "Lord of the Rings" of game stories. Histories stretch millennia and traverse parallel dimensions. And it's all in service of building rich worlds for players to explore.

Enter the arthouse

Over the past 10 years, digital distribution has helped small and independent game makers thrive and build new kinds of games and stories they can tell.

"A lot more things are being tried now in different games than were being tried 20 years ago," says Schafer, who now runs his own independent games studio, Double Fine. "People are afraid to put something into games they haven't seen before, but indie games have done a lot to change that."

Double Fine set the benchmark for crowdfunding video games when it raised more than $3 million in 2012 for Broken Age, Schafer's first adventure since 1998's Grim Fandango. Many independent developers realized you didn't need a bigger company to fund your idea -- just an audience willing to pay for your game in advance.

"Technology has allowed us to...meet up with people with similar interests so we can make things happen for ourselves," says Schafer.

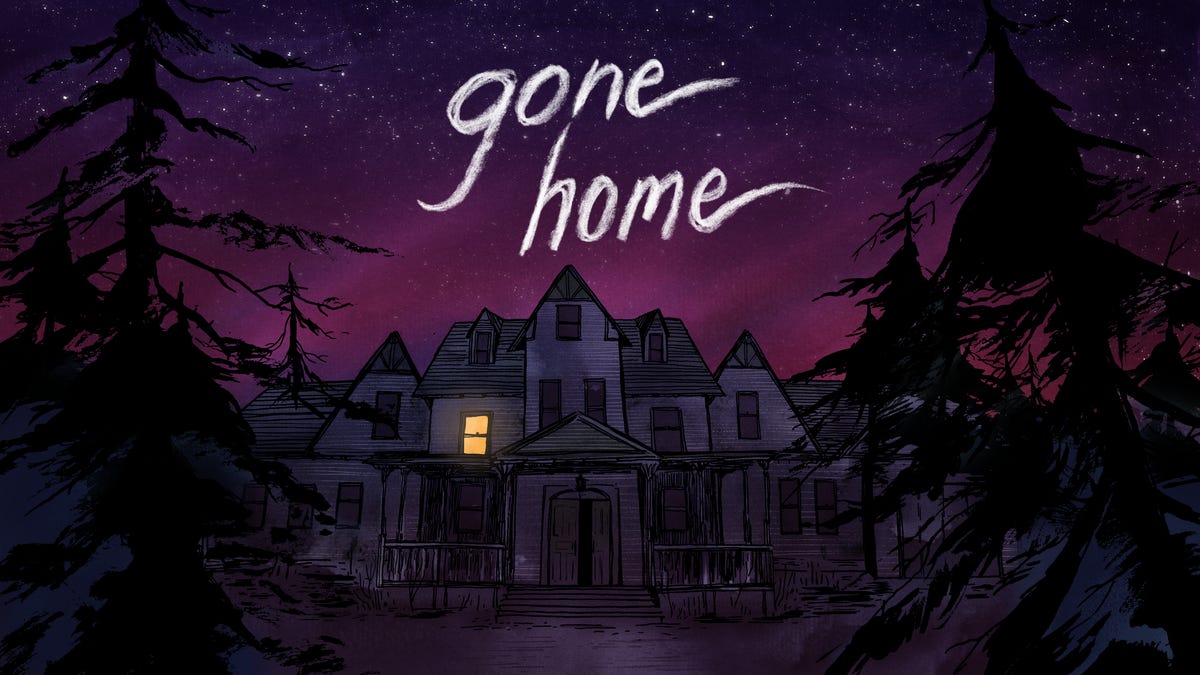

Some games, like Gone Home, have taken the technology used by big-budget, first-person action games and applied it to new styles of storytelling. The game was made by a team that had worked on the successful BioShock series of games -- a first-person shooter series noted for its excellent storytelling within the framework of a blockbuster action game.

This spooky looking house is the setting for Gone Home and it does not deliver the story you might expect at the start.

"We didn't start from saying we want to tell a story about a teenage girl in the '90s," says Steve Gaynor, the designer of Gone Home. The game took storytelling features from BioShock -- such as audio diaries you discover in the world -- and made such exploration elements the entire focus of the game, removing all the action, combat and reflex challenges. That's led to a new genre in video games, the "walking simulator."

See more from CNET Magazine.

"If you can walk around and find notes and objects and hear recordings and be in an environment that contains the entire story and the evidence left behind, what kind of story is it?" says Gaynor.

The Gone Home team chose a family home as the game's environment, creating a story that explores family problems and personal identity -- subjects with deeply emotional touch points for players to explore.

"Our work can be an example of how you can be very hands-off with the player and just trust them to find the experience," says Gaynor. "They can still have a very impactful outcome without you having to push this onto them and tell them what they should think."

As the end music swells and you discover the fate of the Gone Home's lead characters, you might even find that tear in your eye.

This story appears in the winter 2016 edition of CNET Magazine. For other magazine stories, click here.