Why You Can Trust CNET

Why You Can Trust CNET Quantum computers are on the path to solving bigger problems for BMW, LG and others

Steady progress and a burst of new quantum computer types bring these revolutionary systems closer to reality.

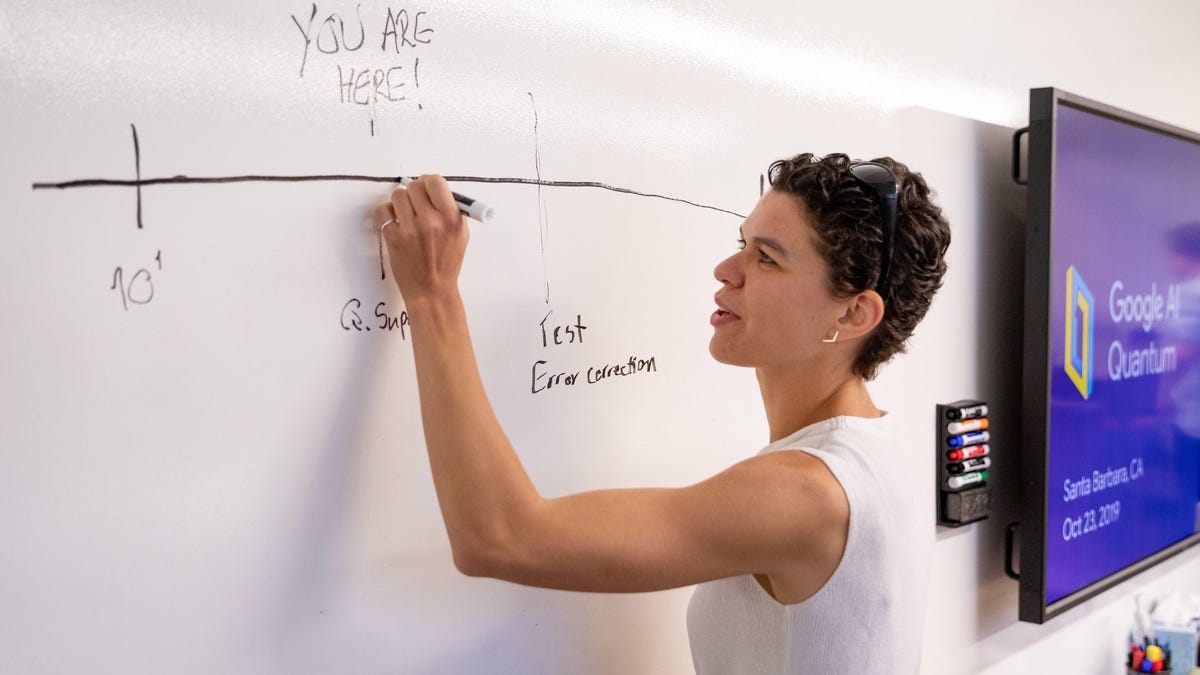

Marissa Giustina, a researcher with Google's quantum computer lab, draws a diagram showing "quantum supremacy" as only an early step on a path of quantum computer progress.

After years of development, quantum computers reached a level of sophistication in 2021 that emboldened commercial customers to begin dabbling with the radical new machines. Next year, the business world may be ready to embrace them more enthusiastically.

BMW is among the manufacturing giants that sees the promise of the machines, which capitalize on the physics of the ultrasmall to soar over some limits of conventional computers. Earlier this month, the German auto giant chose four winners in a contest it hosted with Amazon to spotlight ways the new technology could help the automaker.

The carmaker found quantum computers have potential to optimize the placement of sensors on cars, predict metal deformation patterns and employ AI in quality checks.

"We at the BMW Group are convinced that future technologies such as quantum computing have the potential to make our products more desirable and sustainable," Peter Lehnert, who leads BMW's research group, said in a statement.

BMW isn't alone in its determination to evaluate the practical application of quantum computers. Aerospace giant Airbus, financial services company PayPal and consumer electronics maker LG Electronics are among the commercial businesses looking to use the machines to refine materials science, streamline logistics and monitor payments.

For years, researchers worked on quantum computers as more or less conceptual projects that take advantage of qubits, data processing elements that can hold more than the two states that are handled by transistors found in conventional computers. Even as they improved, quantum computers were best suited for research projects, some as basic as figuring out how to program the exotic machines. But at the current rate of progress, they'll soon become powerful enough to tackle computing jobs out of reach of conventional computers.

Like cloud computing before it, quantum computing will be a service that most corporations rent from other companies. The rigs require constant attention and are notoriously fiddly. Though more work is required to tap their full potential, quantum computers are becoming more and more stable, a development that's helping corporations overcome initial hesitance.

Georges-Olivier Reymond, chief executive of startup Pasqal, says the progress is turning around skeptics who previously viewed quantum computing as a fantasy. A few years ago, employees at large corporations would roll their eyes when he brought up the subject, but that's changed, Reymond says.

"Now each time I talk to them I have a positive answer," Reymond said. "They are ready to engage."

One new customer is European defense contractor Thales, which is interested in quantum computing applications in sensors and communications. "Pasqal's quantum processors can efficiently address large size problems that are completely out of reach of classical computing systems," Thales Chief Technology Officer Bernhard Quendt said in a statement.

Of course, quantum computing is still a tiny fraction of the traditional computing market, but it's growing fast. About $490 million was spent on quantum computers, software and services in 2021, Hyperion Research analyst Bob Sorensen said at the Q2B conference held by quantum computing software company QC Ware in December. He expects spending to grow by 22% to $597 million in 2022 and at an average of 26% a year through 2024. By comparison, spending on conventional computing is expected to rise 4% in 2021 to $3.8 trillion, Gartner analysts predict.

The growing commercial activity is notable given that using a quantum computer costs $3,000 to $5,000 per hour, according to Jean-Francois Bobier, an analyst at Boston Consulting Group. A conventional, high-performance computer hosted on a cloud service costs a half penny for the same amount of time.

Analysts say the real spending on quantum computing will start when the industry tackles error correction, a solution to the vexing problem of easily perturbed qubits that derail calculations. The fidelity of a single computing step on the most advanced machines is around 99.9%, leaving a degree of flakiness that makes a raw quantum computing calculation unreliable. As a result, quantum computers have to run the same calculation many times to provide confidence that the answer is correct.

Once error correction is mature, the revenue generated through quantum computing will explode, according to Boston Consulting Group. With today's machines, that value will likely total between $5 billion and $10 billion by 2025, according to the consultancy's estimates. Once error corrected machines arrive, the total could leap forward to hit $450 billion to $850 billion by 2040.

Software and services that hide the complexity of quantum computers also will boost usage. IonQ CEO Peter Chapman predicts that in 2022, developers will be able to easily train their AI models with quantum computers. "You don't need to know anything about quantum," Chapman said. "You just give it the data set and it spits back a model."

Among the signs of commercial interest:

- Carmaker Daimler and oil giant ExxonMobil have contracted with IBM, an early proponent of quantum computing, to use some of the tech company's 22 machines. (Big Blue will soon be adding Eagle, a new, more powerful device that uses a 127-qubit processor.) The companies are prime candidates for the materials science breakthroughs that quantum computers could someday deliver. They could also use the machines for help with logistics challenges like getting the right equipment in the field when it's needed or the proper components to the factory in time for manufacturing.

- Airbus, LG Electronics, health care company Johnson & Johnson, energy company EDF and chemicals giant BASF are among the industrial enterprises jockeying for time on Pasqal's single quantum computer. The startup is working on a relatively new "neutral atom" design that uses lasers to carefully arrange rubidium atoms then use them as qubits to process data. Many quantum computing startups are in the US, but Pasqal, with headquarters in France, benefits from European customers and government programs.

- PayPal is testing a quantum annealer, a type of quantum computer suited for solving optimization problems and made by D-Wave Systems, to guide its fraud-detection work, according to Vidyut Naware, the company's director of AI research. He also told the Q2B crowd that PayPal is running the test to get a better idea of how quantum computing can be deployed more effectively.

- Amazon Web Services offers customers access to machines from IonQ, Rigetti Computing and D-Wave Systems. It'll soon be adding machines from QuEra and Oxford Quantum Circuits, and is building its own quantum machine. Among those using its services are JPMorgan Chase, which is testing it for optimization work, like managing its clients' investment portfolios.

- Microsoft is working on its own quantum computing approach, called a topological qubit design. The work isn't commercially available yet but Microsoft's Azure cloud service offers access to quantum computers and to quantum computer simulators that are an important stepping stone. The company has also struck a deal with KPMG to help customers test the quantum computing water using Azure.

- Quantinuum, the company formed when hardware maker Honeywell Quantum Solutions merged with software maker Cambridge Quantum, launched a service in December to generate random numbers. That may sound obscure, but such numbers are a foundation for modern encryption. Among those trying the service are Fujitsu and Axiom Space.

- Quantum chemistry software startup Qunasys offers software to customers like Mitsubishi Chemical Corporation, said CEO Tennin Yan. Quantum chemistry and materials science could help engineers find better solar panel materials, electric vehicle batteries and plastics.

Quantum computers today are more of a luxury than a necessity. But with their potential to transform materials science, shipping, financial services and product design, it's not a surprise companies like BMW are investing. The automaker stands to benefit from knowing better how materials will deform in a crash or training its vehicles' vision AI faster. Though quantum computers might not produce a payoff this year or next, there's a cost to missing out on the technology once it matures.